The death of four foreign cyclists on July 29 in Tajikistan – a country and region generally safe and hospitable for tourists – has highlighted the problematic ways in which the regime of President Rahmon handles questions of security and attempts to hold on to power. Expert Artemy Kalinovsky explains how the regime is risking its complicated relations with its neighbors and even tourism, an increasing source of income.

There are now two overlapping theories about what happened. The first, advanced by the government, is that the attackers were connected to the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), banned since 2015. The government also claims that one of the attackers received training in Iran. This version is quite implausible, as I will explain below, and reflects the regime’s obsessions in domestic politics. The second, one that emerged largely independent of the government narrative, is that the attackers were inspired by the Islamic State. In fact, the Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attack via its news outlet, Amaq, and uploaded a video of five young men, dressed in black t-shirts and sitting in front of the Islamic flag, pledging allegiance to the organization. Strangely enough, while the government does not deny the Islamic State link, it has also not foregrounded the role of IS.

The way the security services deal with the attackers invites further suspicion. According to Tajikistan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, the four main suspects resisted arrest and attempted to attack security officials with knives and an axe and were killed on the spot.

Logo IRPT

The idea that the attackers were connected to the IRPT is highly unlikely. The IRPT is a parliamentary party first organized in the late Soviet era, one of several such parties that emerged across the former USSR. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Tajikistan descended into Civil War (1992-1997) whose divisions were regional as much as ideological or political. The IRPT became one of the partners of the so-called United Tajik Opposition (UTO), which, along with supporters and families, was forced to escape to Afghanistan. Peace accords, signed between the government in Dushanbe and the UTO in 1997, allowed the latter to return and guaranteed the former belligerents a role in politics and economic life.

In the years that followed, the IRPT became an effective parliamentary party. Although its members were gradually squeezed out of government institutions it remained a vocal and active party until it was banned in 2015. A part of the IRPT leadership, including the leader Mukhiddin Kabiri, has fled the country, others have been jailed on dubious charges. The IRPT has denied any connection to the attack and has repeatedly renounced terror. Even in exile it has continued to call for opposition to the regime using democratic means; it has not expressed any interest in fomenting an armed uprising within Tajikistan. Nor has it ever espoused any particularly xenophobic views about Europeans or anyone else. On the contrary, both before and after his exile, Kabiri has always looked to Europe to pressure the regime of Emomali Rahmon, president since 1992, to live up to its promises. In short, while it cannot be ruled out that some of the attackers may have once been IRPT followers, it is highly unlikely the group had any involvement in the attacks.

Adherence rally for President Rahmon in Dushanbe, 2016. Photo AFP

Single minded obsession

So why have Tajikistan’s security services embraced this interpretation? Even before 2015, the Rahmon regime developed a single-minded obsession with the IRPT. Endemic economic problems leave the regime unsure of the loyalty of its young and rapidly growing population. Moreover, the regime maintains stability through a sprawling system of patronage that connects business figures, government officials, and members of the president’s family. Not surprisingly, the regime’s moves against the IRPT were preceded and moved in tandem with the seizure of economic assets, including lucrative urban markets, which were then redistributed to loyal individuals or family members.

Most importantly, perhaps, the IRPT was the only political force (aside from the regime) that attracted significant support among the country’s youth. This was true even among youth who were not particularly pious. Somewhat like the Turkish AK-Party of president Erdogan, the IRPT appealed to a broad range of young people looking for an alternative to the cronyism, corruption, and stagnation of the regime.

The Communist Party, the other main opposition party, has also been pushed out of parliament, but since it controls few economic assets and has little support among youth it was not as dangerous to the regime as the IRPT.

Last but not least, the regime has clearly been frustrated by Kabiri and the IRPT’s ability to get a sympathetic ear from western governments. Kabiri has been able to get asylum in an EU country and remains active in émigré circles. The regime has successfully brought back or killed dissidents in Turkey and Russia (it is one of the world’s most prolific users of Interpol 'red notices',) but has been frustrated in Europe. In March, Interpol removed Kabiri from its list, angering the regime. By blaming this attack on Europeans on the IRPT, Tajikistan’s security services clearly hope to demonstrate to western audiences that Kabiri and his allies are terrorists, not politicians.

The attempt to link Iran most likely comes from the same motivation. The Islamic Republic of Iran and Tajikistan, which share a common language and literary heritage (though contemporary Tajik is written in a modified Cyrillic script) have had a generally positive but occasionally tense relationship since Tajikistan’s independence in 1992. Tehran angered the Rahmon regime by inviting Kabiri to a conference in December 2015, just months after the IRPT was banned. Iran is a known supporter of militant groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon, but it does not, as a rule, train terrorists for small scale attacks. It is not a supporter of the Islamic State, which it is fighting in Syria as part of its support for the regime of Bashar al Assad. In short, the idea of Iran being behind this attack is ludicrous to any half-competent analyst of the region.

Mukhiddin Kabiri. Photo Sputnik.

Islamic State?

So what was behind this attack? Considering that our knowledge of the suspects will be mediated almost entirely by Tajikistani authorities, we may never get a very full picture. We know that the Islamic State has recruited heavily among Central Asians, although the number of Central Asians fighting alongside the Islamic State is much lower than that of French or Belgian citizens, for example. We also know that many of these volunteers are recruited while working as laborers in Russia – often the only employment option for young men from the region.

However, it seems most likely that the young men involved in this attack made contact with the Islamic State via the internet, and decided to pledge allegiance to the group and carry out an attack. It is unclear whether ISIS actually directed the attack, or as is most likely the case, served as inspiration. Certainly the attack did not require any complicated preparation or training.

Controlled freedom of religion

In explaining why people from the region might volunteer for the Islamic State or other terrorist organizations, commentators sometimes turn to two equally problematic explanations. One is that people in the region are somehow particularly prone to violent extremism. The other, usually offered by well-meaning commentators, is that it is the regime’s repression of Islam that drives people to commit violent acts.

Yet while the regime is certainly repressive, it is hardly anti-Islamic or even anti-religion. It does not, generally speaking, forbid people from attending mosques or going on the Hajj. On the contrary, the regime sponsors the construction of mosques and regime representatives publicly take part in religious rituals.

But the regime does seek to actively control religious practice and institutions, in part through its system of oversight of officially registered mosques, imams, and through rules that forbid minors to attend prayers. It also pays obsessive attention to external manifestations of piety, such as long beards on (young) men or black head-coverings among women.

The problem is not that the regime is anti-Islamic, but rather that when all institutions and practitioners need the state’s seal of approval (or are in effect the arm of the state), they are also tainted with the regime’s corruption and illegitimacy. Thus people who are dissatisfied with the regime, however pious they might be, are unlikely to be convinced by religious authorities preaching loyalty to the state. Instead, they lose trust in these institutions and look for religious authority elsewhere, through personal networks and on the internet.

In this sense, the government’s banning of the IRPT is likely to backfire. Not only did the IRPT provide an outlet for people looking for a more pious form of politics than that offered by the ruling party, it was also led by veterans of the Civil War who could speak eloquently on the need to avoid a return to violence. The regime has effectively silenced the most effective voice for non-violent politics in the country.

Government troops during the civil war, 1992-1997. Photo Pinterest.

Geopolitical consequences

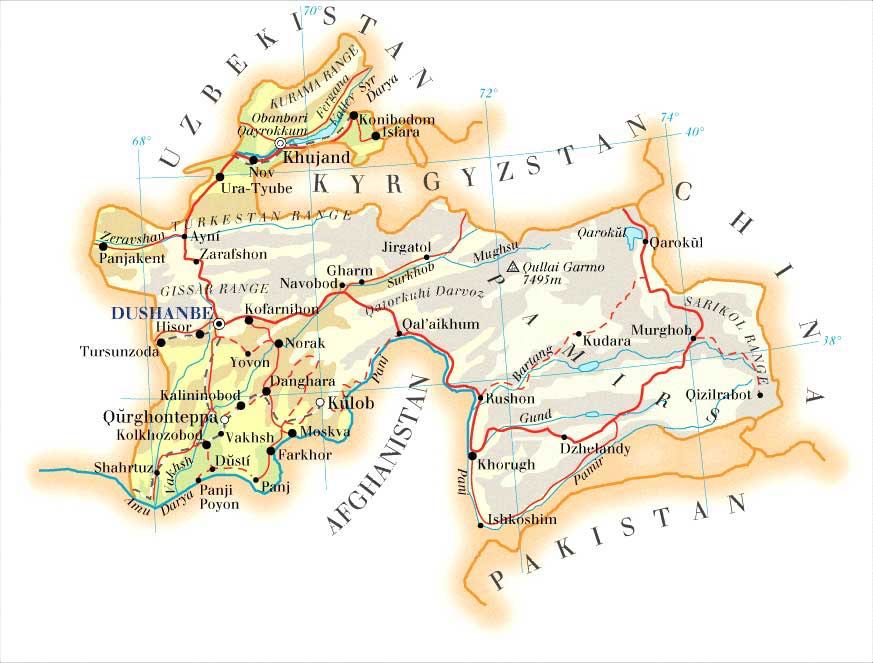

The regime’s response to the attack shows how short-sighted it has become. President Rahmon has preserved freedom of maneuver by balancing between Russia (its main security partner and destination for labor migrants), China (its main investor), the United States, and Europe.

A country actively trying to draw tourists would be expected to explain this away as a rare attack by a distant foe. Instead, it has suggested that the main culprit is an organization that still has roots in the country. Putting part of the blame on Iran unnecessarily strains relations with Tehran. It is hard to see what the regime hoped it could get out of doing so, considering that Iran maintains good relations with Dushanbe’s main patron, Russia. Perhaps it hoped to win support from Washington, since President Trump has pursued a belligerent anti-Iran line since coming to power. Most likely, however, this was just an opportunistic attempt to lash out at Iran for hosting Kabiri.

Bike tourism in Tajikistan.

The governments and citizens of the United States, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, where the cyclists were from, will no doubt be frustrated by the way Tajikistan’s security services are investigating the case and sharing information. They should be wary, too, of attempts to draw them into further security cooperation. The most charitable explanation of the security services behavior in the last few days is that they have a weak understanding of their own best interest.