For decades Russia and the West are looking for a ‘reset’ of their relations. To no avail. Who’s to blame? That’s the wrong question, says Sir Andrew Wood, former diplomat in the Soviet Union and Russia. With Putin in the Kremlin and Trump in the White House, it’s time for dealing with particular problems as best we may, not to succumb to the destabilising myth of defined spheres of special interest.

by Andrew Wood

Associate fellow Chatham House

Dmitri Trenin's address of 18 May to a conference at The Hague has led to a debate organised by the RaamopRusland think tank as to where the blame lies for the current estrangement between East and West.

Trenin is the Director of Carnegie Moscow and also an experienced and authoritative exponent of views widely held within the Moscow foreign policy establishment. In setting out his inevitable conclusion that the United States bears the principal responsibility for the present situation, he argued that the Soviet Union lost a real war, call it ‘Cold’ though we do, to the United States and that today's Moscow is justified in reasserting itself because of the dismissive way that it was treated by Washington thereafter. Russia, as the successor state to the USSR should have been taken by Washington as a co-equal in deciding the affairs of lesser nations, not least in Europe.

Soldiers of US and Soviet Army shake hands at the river Elbe, spring 1945. Photo Reddit

Cold War: no military conflict like World Wars

Such arguments are at the root of ideas shared by many believers in the current Putin narrative of Russia being obliged to reject what they see as the humiliation that the West has visited on Moscow, with the United States leading the pack. It is buttressed by the manner in which the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945 has been built up since Putin became President, with the implication that the Russian people in particular are owed a special place in the world because of it.

It is however misleading to imagine the Cold War in retrospect as a military conflict expected to conclude in a formal set of treaties, let alone formal surrenders like those which ended World War I in 1918, or its successor in 1945.

The Cold War was, it seemed at the time, taken off the table with a series of agreements reached over the years designed to protect the security interests of all the parties affected by what turned out to be an accelerating process of change within wider Europe as a whole, including of course Russia. That, again at the time, seemed a benign, unexpected and responsible way for the Cold War to have been resolved.

There were of course dangerous times in Europe after 1945 but to suppose that between 1945 and the later 1980s Washington was engaged in active war against the Soviet Union with the aim of its military defeat would be untrue. The United States and its NATO Allies stood sometimes nervous guard against what they saw with some justice as a threat from the Soviet Union, and there were rivalries and conflicts beyond Europe not unlike those that troubled European peace before 1914, but none of that makes it right to envisage the Cold War as a real war ending with Russia being cheated of its due as it reached a formal conclusion.

More internal decay than outside pressure

Nor, second, is it accurate to see the Cold War as being primarily a conflict between the United States and the USSR, let alone one that had for the main part to be resolved between Moscow and Washington.

It sometimes appears hard for Russian observers to understand that NATO is not and never has been Washington's to command, in the way that the Soviet Union was able to direct the Warsaw Pact. But a reasonable grasp of history ought to be enough to prove the point that there were then independent strains of policy within the West - as there still are.

West wasn’t responsible for disintegration of Soviet Union

It is perhaps even more to the point that the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, and the disintegration of the Soviet Union which followed it, stemmed from the internal decay of the USSR and the eventual defeat of military force used by Moscow to ensure the subservience of its own ostensible allies. East Germany, Hungary and Czechoslovakia were invaded in 1953, 1956 and 1968. Poland was threatened with military intervention at different times. Yugoslavia defied Stalin in 1948 to secure its independence as a Communist state governed by its own interpretation of what that meant. Romania later achieved a degree of Chechnya like autonomy before its eventual collapse. Neither the West in general nor the United States in particular played an initial or decisive part in any of these events. Nor can it seriously be maintained that Washington or any outside European power were responsible for the eventual disintegration of the USSR.

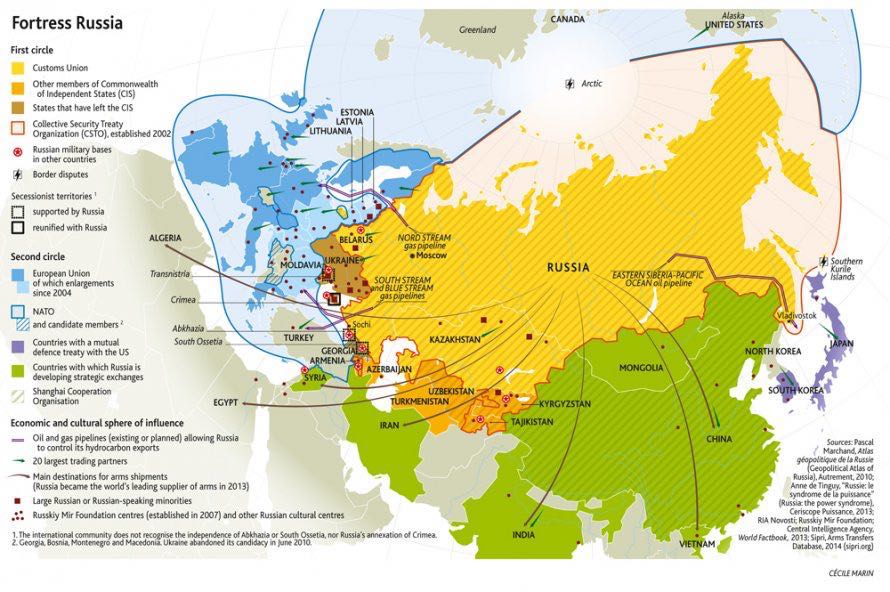

After the Cold War. Graphic Le Monde Diplomatique

Russia haunted by the Soviet past

Third, Russia today is not the Soviet Union of the past, but a state ruled by a regime haunted by it. Russia is not, in principle, different from other European states.

But Russia has yet to work out what its thought-through role now should be as a major part, but a part among others, of a wider Europe, including other states that were once, like Russia, components of the USSR. The fact that the Soviet Union was held together by force from Moscow and with the help of a common ideology, however much now discredited, is a dominating though not generally articulated political memory behind the Kremlin's preoccupation with international power and tight, centralised, domestic control, rather than with the useful pursuit of the broader contemporary interests of Russia's people. It is, too, an important motivating factor behind official Russia's obsession with the United States.

Creative questioning and debate within Russia has been steadily repressed over the past eighteen years, making it more and more difficult for different approaches to the country's foreign interests to be aired in Moscow, however timidly.

Fortress Russia is an emotional prejudice

That repression has helped to feed the emotional prejudices that lie behind the Fortress Russia proposition. Taking the United States to be your principal enemy as for instance Trenin did on 18 May (‘Russia's conflict is not with the West, it's with the USA.

By and large Europe is caught in a crossfire.’) may be, and indeed is, questionable, but such beliefs, which are encouraged by official propaganda, are now widely shared. They also give some compensatory balm to the disquieting realisation that Russia is no longer in any real sense a counter-weight or rival to the United States, as the USSR once was. Russian policy makers furthermore appear to take no account of the probability, even certainty, that Russian actions will provoke foreign reactions in response, or to the damage that has been done to their country's reputation and leverage by the regular indeed instant denial of responsibility for malign actions however credibly laid at their door. But a degree of trust and an expectation of possible mutual concessions in the wider interest are essential to useful dialogue, let alone successful negotiations.

Trenin, as have many others, has advocated a partnership of equals between Washington and Moscow such as, according to him, was rejected by the Americans from the start, leaving Russia ‘lying somewhere’. Russia's annexation of Crimea - and by implied extension, invasion of the eastern Ukraine – ‘in a way was predictable’. Trenin, again on 18 May, remarked revealingly that the United States ‘hits you...[but] also ignores you’. Russia had from the start refused to accept what the Russians saw as the American demand for a US leadership ticket. As a sentiment, that would be understandable, and even reasonable if you believed that this was indeed being demanded.

The claim has been expanded over the years to the assertion that the United States' objective is to imprison Russia into an international liberal order, in which Washington makes all the rules.

Russia is not alone in its concerns as to the way that the United States, especially under the present Trump Administration, tries to force its way in particular cases. But the United States has not in fact tried or been able over the years unilaterally to draw up the international rule book that has by and large been in accepted international force for decades. There is the further problem of what exactly Russia would like to see take its place.

Spheres of special interest?

Moscow's essential proposition to Washington is apparently that each should respect and if need be formalise the other's sphere of special interest. There are those in the United States that have some sympathy for this approach. It is however difficult to set out what it might mean in practice, beyond if taken literally, licensing a Hobbesian world of conflict.

None of the mooted poles of power can determine what happens in the spheres of special interest assigned to them by the modellers: Washington, Moscow, Brussels or Beijing. That would include, in Moscow's case, Ukraine. Even if that country were to be subdued to the will of the Kremlin by military force Russia would not be able to secure its reliable allegiance. Nor would the by now pretty much still-born Eurasian Union pursued by Putin since 2012 be revived if the United States were to achieve a ‘Grand Bargain’ with Russia as between one Great Power and another at Ukraine's expense.

Which European state would accept Moscow's diktat?

‘Finlandisation’ was the product of particular circumstances, which do not apply to Ukraine. One of those was the Cold War militarised division of Europe between two rival camps. The supposition that Russia has a sphere of interest justified by its security needs is a pale reflection of that. No other state in Europe would willingly accept the subordination to Moscow's diktat which would go with accepting a tributary role in an arbitrarily defined ‘sphere’. It is the attempt to force others into such a condition, or the fear of it as a possible threat, that has led many to seek shelter in NATO, or if that is not on offer, to get close to it.

Ten years of resets

The United States has tried a number of times to ‘reset’ its relations with Russia, after what was an initial attempt to form a close relationship with Moscow on the formation of Russia as a new and independent country.

Russian propaganda poster. Picture MID Russia

The op-ed of Eugene Rumer, the Director of the Russia and Eurasia Programme at Carnegie Washington, in The Moscow Times of 31 July (‘Russia Is Winning - Or is It?’) is only the latest account of the breadth of that initial yet ultimately unrewarded effort. President Obama tried in his turn to improve matters, in concert with the then Russian President, Medvedev, who at the same time encouraged discussion within Russia of possible economic and by extension political reforms. All of these attempts ended in failure.

President Trump met President Putin on 16 July in Helsinki in what in general terms he would like to suppose will bring about good and sustainable relations between Moscow and Washington, underpinned by a viable partnership between Putin and himself. There were no signs before the meeting of any tangible changes in Russian policies, whether domestic or foreign.

Nor have there been any after it. The little we know of what was discussed between the two Presidents in their private encounter, which took up most of the time in Helsinki, is limited. It was agreed that there would be an experts group to discuss questions of mutual interest, pretty much like the one that existed in vain during the Obama/Medvedev reset. President Trump ran into a firestorm of criticism on his return to the United States, including for the contrast between the way he had treated America's allies during his trip to Europe, and his fawning on President Putin. Further meetings between Trump and Putin have been bruited, and familiar topics such as terrorism, cyber issues, Syria, arms control and perhaps Ukraine in some form or another have been mentioned as being on possible agendas. But little or nothing has been reported as to how such generalised topics can be given sufficient concrete reality for progress to be made between the two Presidents, or for them to become over a longer term the building blocks of a future new and effective joint action oriented agenda between Russia and the United States.

Who’s to blame? Wrong question

The question of who is to blame between Washington and Moscow for the estrangement between them, or rather between Moscow and the West, seems to me to be the wrong question.

Dmitri Trenin suggested that the blame rested with Washington, the United States being the stronger power. Others might point their fingers at the Kremlin, with cogent examples to support them. But the pursuit of a bilateral US/Russia relationship as the decisive factor in achieving a healthier relationship between Russia and the West is a chimera stemming from assumptions derived from the Cold War era. Neither Washington, which in any case has other preoccupations than dealing with Russia, nor Moscow, which may be more focused, can command the obedience of other countries, in Europe and for that matter outside it too. These countries have their own concerns to nurture.

Russia has evolved in such a way that Trenin can convincingly assert that his country will not accept the tutelage of the USA, and to believe that this is a real threat that Russia must face. Other countries are not ready to accept the tutelage of the Kremlin, for that matter, and to defy the prospect of it being imposed upon them. Neither power, whether the stronger or the weaker, can look to bilateral negotiations or for that matter bilateral competition to decide for others what the outcome should be in particular cases. Not even the Cold War itself was dissolved on that basis. Europe today is evolving in uncertain ways. Russia will not remain in its present condition for ever. The United States has a troubled Administration.

This is a time for dealing with particular problems as best we may, not to succumb to the destabilising myth of defined spheres of special interest, and inherent contradiction between rival poles of power.