We can keep laughing at the Russian military intelligence service, says our columnist Mark Galeotti, but we should try to understand what the Kremlin's motives are. Its blunders speak of a growing isolation of Putin, who gets rid of people who criticize him. But if he cannot be friends with the West, what options are left?

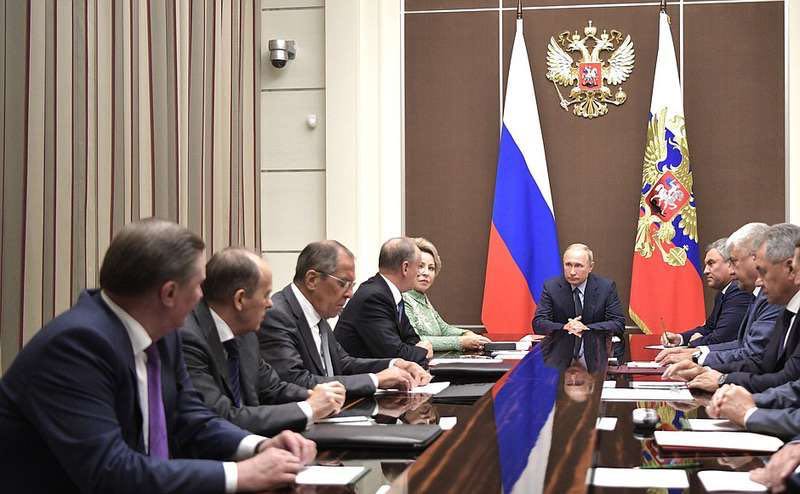

Putin with his Security Council (picture Kremlin.ru)

Putin with his Security Council (picture Kremlin.ru)

Much of the discussion about the recent revelations of Russian intelligence activity abroad now boiled down to a simple question: how could they be so stupid?

Of course, there were human blunders both serious and trivial. Arguably, the biggest left over 300 military intelligence officers of the military intelligence service GU (still widely known by its older name, GRU) unmasked because they registered their cars at their workplace in a database that, while not public, is hardly secure, either. Others were laughable but in reality not really worth mention. Keeping a taxi receipt linking you to your base only matters when your pockets, luggage and hire car are being searched, which means they probably know you’re a spy, after all.

So, sometimes stupid, sometimes not. But the GU is no wildcard service, it is doing what it is told to do, within the parameters of its orders. It is only now that a critical mass of bad news has emerged that the Kremlin appears to be communicating its displeasure, but it had no problems with its spies until they started getting caught. And this, to an extent, was inevitable, especially when they engage in the kind of murderous theatre as the Skripal case.

So the question really ought to be, how could the Kremlin be so stupid? How could it possibly believe that the benefits could outweigh the risks? It is not that these are only damage to its reputation, although in politics, prestige is power, but also to its intelligence networks, and as a result of sanctions, its economy.

Putin's gamble

The first answer is that, overused clichés about chess-playing grandmasters notwithstanding, the Kremlin is no better, and sometimes worse, at predicting outcomes that anyone else. Putin gambled that he could get away with taking Crimea and, in fairness, this was probably a good bet given the massive domestic boost it provided. Had he stopped there, especially if he had held a proper, internationally-monitored referendum, it’s possible that by now it would have the status of the Baltic States in Soviet times – formally, occupied territory, but de facto accepted as part of Moscow’s dominion.

He didn’t, though: the ease of the annexation tempting him into a crucial overreach into the Donbas. The consensus in Moscow’s national security circles was that stirring up a proxy war would quickly induce Kyiv to capitulate and accept its position as part of Russia's sphere of influence. Everyone I spoke to in Moscow in those days was confident: within six months, Ukraine would be back in the fold and the war would be over. More than four years on, with the Russians continuing to have to pour political capital, soldiers and money into a war over a territory it doesn’t even want, the scale of this miscalculation is clear. However, the point is that it made perfect sense – if the predictions on which the decision was taken had been right.

So is it simply that the Kremlin keeps making bad decisions based on bad intelligence and bad advice? There is an element of truth in that. The sense I get with the Skripal case, for example, is that while the Russians anticipated the ritual tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions with London, they were not expecting the wave of coordinated international expulsions which followed.

But how many times do you have to get it wrong before you begin to wonder if there is some more systemic problem in the process? At what point do you begin to question whether you are getting good intelligence? (My sense is that for years Putin has been being told good news that people think he wants to hear, not the bad news he needs to hear.) At what point do you begin to wonder if you are getting counsel from the right people? (Likewise, for years Putin appears to have been sidelining those who question his assumptions and challenge his worldview.)

Whatever else he may be, Putin is no fool, and Russia's place in the world is an important element of his campaign to build his political legacy. Indeed, as it becomes clear how complex and intractable managing the economy and tackling the domestic agenda is, arguably it has become his focus. He certainly seems to give it most attention, and it generates the most passion from this increasingly jaded-seeming tsar.

Unless we are willing to believe that Putin is wholly cocooned from reality, then there has to be some reason why the same mistakes keep getting made.

Cost-benefit calculus

The first answer may be that we don’t understand his cost-benefit calculus. Maybe the GU's operations overall, those that haven’t been uncovered, are delivering immense results, such as to outweigh the costs. However, it is hard to see how these may be bringing concrete benefits.

So has he decided Russia should be the best rogue state it can be

More plausibly, Russia's reputation as a ruthless, desperate and daring insurgent power is actually part of Putin's geopolitical approach. Machiavelli said that if you cannot be both loved and feared, it is better to be feared, and Putin may agree. Whether deterring further would-be spies, or warning countries not to challenge Moscow, or simply to encourage the timid that it is better to make a deal than take a stand, he may have given up on the thought that he can make friends in the West with anything short of capitulation. So he has decided Russia should be the best rogue state it can be. In some ways, this is the North Korean solution, albeit resting on active and covert subversion rather than a nuclear programme.

There is a certain logic there, but only in its own frame of reference. From the point of view of Russia's technocratic elites, this is foolish, disastrous, senseless. The tragedy is that, especially in Europe, there is such despair at the current level of tension that any meaningful Russian de-escalation would likely be met with enthusiasm. A deal that traded peace in the Donbas and an end to Russia's campaign of chaos in the West for de facto recognition of the Crimean annexation and a lifting of most sanctions would not be inconceivable.

It seems hard to believe that Putin is able to be so flexible, however much it would actually be a triumph for him. More to the point, those technocrats’ voices seem not to be heard in this inner circle. He is happy to grant figures such as Central Bank chair Elvira Nabiullina considerable latitude in economic management, but their role is limited to mitigating the impact of sanctions and doesn't touch upon the still excessive spending on defence, espionage and foreign adventures, not speaking out against their causes.

To step back would be defeat

Has Putin exhausted his capacity for reform and reinvention? Probably. Like Macbeth, he seems to believe himself 'in blood stepped in so far that should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o’er'. If, in his eyes, to step back would be a defeat, then what is left but to step forward? This is war – even if political war – as the Kremlin sees it, and all Russia’s great triumphs have their tragedies and their reversals, and the road to glory is often paved with mistakes and martyrs. But this is not the Great Patriotic War (as Russians call the Second World War till this day), or its predecessor the Patriotic War with Napoleon. There is no mortal foe marching to Moscow’s gates except in the Kremlin’s collective nightmares. But if you believe there is, then a dead bystander in Salisbury, some embarrassing news cycles, even sanctions, all look like acceptable prices to pay for that final, fantastical victory.