Never a dull moment. This is the feeling one has when observing the tumultuous turns of events in the complex entanglement of energy and politics involving Europe, Russia, the US, and countries in the neighbourhood. The US imposes sanctions on Nord Stream 2 and the energy market is politicising. How should we interpret recent events? Is the EU-Russia gas relation a liability? Who profits the most from it? Energy expert Luca Franza argues that the EU has no reason to be afraid of dependency from Russia.

Gas pipelines to Europe. Graphics RFE/RL

Gas pipelines to Europe. Graphics RFE/RL

by Luca Franza

On 21st December, Russia and Ukraine finally announced the terms of a new gas transit agreement after months of drawn-out negotiations. This welcome development dispelled fears that an impasse between Russia and Ukraine might leave Europe in the cold.

But the night before, while the announcement was imminent, Trump had signed into law sanctions from Congress targeting companies involved in the construction of Nord Stream 2, a Gazprom-sponsored direct pipeline between Russia and Germany (and bypassing Ukraine).

A couple of weeks later, Putin and Erdoğan inaugurated Turk Stream, another pipeline bypassing Ukraine and linking Russia and Turkey across the Black Sea, which will later connect to South-Eastern Europe.

This happened six days after another energy event had turned the spotlight on a region nearby: the signature of an agreement between Greece, Israel and Cyprus to build a pipeline carrying East Mediterranean gas to the EU, effectively sidelining Turkey.

These events took place against a background of immense uncertainty at a global level, where oil and gas are ensnared in US-China trade disputes, geopolitical volatility around the Strait of Hormuz, and Saudi-Russian price wars.

In December, the new EU Commission, which declares itself the most ‘geopolitical’ ever, presented a very ambitious European Green Deal, which aims to boost the EU’s global leadership in energy and climate as well as to cut EU energy dependency. An attempt to limit the EU’s exposure to growing instability in global energy markets.

Reading what is going on, and imagining what the future might bring, is complicated. Also, too much disinformation is polluting the debate.

This article sheds light on evolving EU-Russia energy relations, with a focus on gas, against the volatile global context sketched above. How should we interpret recent events? Is the EU-Russia gas relation going to last? Who profits the most from it?

Russia-Ukraine gas transit deal

Let us start with the new gas transit agreement between Russia and Ukraine – inked in a context of improved relations, notably marked by a ceasefire and an exchange of prisoners in December.

The deal reached at the very end of 2019 is important because it essentially resolved the only major security of gas supply issue that was threatening the EU.

For the rest, things were already going quite well: in fact, for years, the EU has been enjoying plenty of cheap gas coming from a diversified pool of suppliers – including Norway, Algeria, Qatar, and the US.

The agreement now guarantees uninterrupted flows of Russian gas through Ukraine for another 5 years. It is a half-way compromise between Ukrainian demands to strike a 10-year contract and Russia’s preference for minimising commitments.

The EU, which initially supported the 10-year solution, gradually came to favour a shorter one. The reason is political: as the decarbonisation agenda became more and more pervasive, EU negotiators did not want to be perceived as pushing for a long-term commitment to fossil fuels.

The deal resolves the security of gas supply for the EU and guarantees 5 years of transit revenues for Ukraine

Pursuant to the transit deal, Gazprom will guarantee minimum shipments of 65 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2020. Guaranteed transit will then go down to 40 bcm per year between 2021 and 2024. This is certainly a reduction relative to physical shipments in 2019 (~90 bcm). Indeed, in 2019 Ukraine-bound shipments were at historically high levels.The reason is that Russia has been exporting record volumes to the EU, and alternative pipelines were not available. Ukraine transit was thus the only option for Russia not to lose European market share to LNG.

In any case, the guarantees contained in the December agreement should be regarded as satisfactory also for Ukraine.The transit of 40 bcm per year ensures sufficient pipe pressure for the Ukrainian system to function from a technical perspective. Moreover, such volumes will still bring quite a lot of transit revenues to the Ukrainian government (7 billion $ for 5 years, i.e. 1% of GDP, or about 5% of the State budget).

While this might not seem much, we should not forget that Ukraine is a country in financial trouble. Western countries are very much aware of this, and one of the reasons why they supported the deal is that they did not want to refill Ukraine’s coffers more than they already do.

Ukraine is Europe’s second poorest country, with a GDP per capita lower than Indonesia’s, Bolivia’s, or Sri Lanka’s. Energy poverty is a pressing issue. In this respect, it is relevant to highlight that there were talks of resuming direct exports of Russian gas to Ukraine (for Ukraine’s domestic consumption), which were discontinued in 2015 due to conflict. Since then, Ukraine has been de facto importing Russian gas through the EU through reverse flows. Importing directly from Russia would be much cheaper, but it is a hard sell politically in Kiev. Russia would also favour the option because it would leave larger usable capacity in its other pipelines to the EU.

Nord Stream 2, Turk Stream and US sanctions

For Gazprom, determining the ideal amount to be shipped through Ukraine is difficult, as it depends on when Nord Stream 2 (55 bcm/y) and the second line (15.75 bcm/y) of Turk Stream – together with Turk Stream’s planned connections to Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary and Austria – will be ready.

Serbia said that it has completed the pipeline section in its territory, while work is ongoing in the interconnector with Hungary and within Bulgaria. Turk Stream further strengthens the Russian-Turkish partnership, already boostedby Ankara’s purchase of advanced defence systems (S-400) from Moscow.

Turk Stream increases Turkey’s role as a transit country for the EU, which will also be strengthened by the imminent passage of Azerbaijani gas through the TANAP-TAP system. The reliability of Turkey is being increasingly questioned given the well-known developments in EU-Turkey relations.

While Turk Stream is unlikely to be practically affected by US sanctions,Nord Stream 2 is.

American sanctions are an agressive tool of geopolitical and geo-economic coercion

The reason is that Gazprom needs specific pipe-laying vessels owned by Allseas, a company headquartered in Switzerland but with strong ties to The Netherlands (being part of the Heerema family empire). Allseas was forced to stop work off the coasts of Denmark in December because it has business interests in North America, and the risk of falling prey to US sanctions is too high for any company with a global outlook and the need to access international, dollar-denominated financial markets.

Sanctions came at a very late stage of project execution and were an aggressive tool of geopolitical and geo-economic coercion. For a long period, it could have been possible to think that the US was simply threatening sanctions to convince Russia to sit at the negotiating table. But because the Russia-Ukrainetransit deal was being reached in the same days that the US sanctions were imposed, this argument does not seem to hold.

When Denmark (belatedly, due to US political pressures) granted the necessary environmental permits for Nord Stream 2 to continue working, Russian sources indicated that they needed another 5 weeks to complete the pipeline. The estimated launch date then became mid-2020, as the pipeline needed to be tested and ramp-up could only be gradual. In any case, work was almost finalised.

Now, after the imposition of US sanctions, there is much more uncertainty surrounding the timeline. Putin says that Nord Stream 2 will be ready in early 2021. One option is to use a smaller Russian vessel such as Akademik Chersky, which is reportedly en route. It is almost certain that the Russians will find a way to complete the pipeline by themselves: the project is 95% complete, and Gazprom invested 4.75 billion euros in it (the same amount was provided by five EU companies: ENGIE, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper, and Wintershall).

Russia needs Nord Stream 2 to sell large amounts of gas to the EU and compete with American LNG

Moreover, Russia needs Nord Stream 2 to continue selling large amounts of gas to the EU and compete with US LNG. Transport bottlenecks risk leaving Russian gas underground. Russia has a few alternatives, but the EU market is still key.

Russian exports to China and Russian LNG

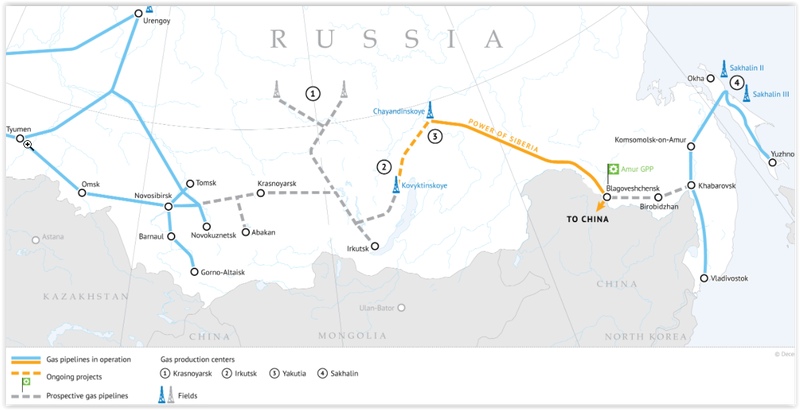

One alternative for Russia is China, where gas demand is booming as the government promotes its ‘Blue Skies’ policy aimed at curbing pollution, to which coal-to-gas switching is key. Power of Siberia, a pipeline connecting Eastern Siberian fields with China, has become operational at the end of 2019, although it is only working partially. At full capacity, it will ship 38 bcm of Russian gas per year to China (compared to ~200 bcm per year sold in Europe). However, it is important to highlight that China cannot be supplied from Western Siberian fields (from where the bulk of Russian gas is extracted), because there are insufficient internal West-East connections in Russia. For this reason, China and the EU do not compete for the same volumes of Russian gas.

Power of Siberia pipeline (yellow). Graphics Gazprom

Power of Siberia pipeline (yellow). Graphics Gazprom

Another alternative for Russia is LNG. The most important LNG project is the Yamal terminal – led by independent gas producer Novatek (in partnership with France’s Total and China’s CNPC and Silk Road Fund). This project, built in a very difficult environment, came on line according to schedule and with no cost overruns. Gazprom’s track record in LNG has not been as brilliant, and people in the Kremlin have noticed it. Gazprom is thus being scrutinised and it’s under immense political pressure to at least keep on shipping a lot of gas to Europe.

China's gas demand is booming, but Russia has limited capacities to ship the gas

With a capacity of 21 bcm per year, Yamal LNG opened up new markets for Russian gas and created a new route to reach the EU, where it actually started to compete with Gazprom gas. In 2019, Novatek and its partners made an investment decision on another terminal (known as ‘Arctic LNG 2’, with a capacity of ~25 bcm per year), which will become operational between 2023 and 2026. Due to growing ice melting in summer months (provoked by global warming) LNG from Northern Russia will be shipped to China using the Northern route rather than by circumnavigating Europe, cutting shipping costs.

Yamal LNG project. Photo: Novatek

Yamal LNG project. Photo: Novatek

US LNG, its competition with Russian gas, and the implications for the EU

But the real LNG game changer is US LNG. This new source of gas, the result of the ‘shale revolution’ that has taken place in the US since the mid-2000s – and that has rendered the US a net exporter of natural gas – has already transformed global gas market dynamics. US LNG is a highly flexible source of gas. It is sold by private companies to the highest bidder (apart from some contracts with Poland and Lithuania, where buyers are willing to pay a ‘diversification premium’). This means that if buyers outside of Europe offer better prices (depending also on shipping cost differentials) shippers of US LNG would supply them instead of Europe. US LNG is thus usually not a ‘guaranteed’ or ‘point-to-point’ source of gas.

The American shale revolution has transformed the global gas market dynamics

Since mid-2019, quite a lot of US LNG has been coming ashore in the EU because US supply has been growing fast (as a result of investment decisions taken earlier this decade), Chinese GDP growth has been lower than expected, and other emerging markets have gradually become saturated. In sum, the EU has been a ‘market of last resort’ for US LNG in the last months.

This is actually a good position to be in for the EU, because it entails that the global market is oversupplied and prices are low. US LNG and Russian gas, which also became more flexible and market-priced as a result of new EU rules and contract renegotiations since 2009-2010, compete head to head in the EU. In other words, Russia is a price-taker. Even if it sells very large volumes to the EU, it cannot manipulate the market. The moment Gazprom were to try and play ‘value-over-volume’ strategies (i.e. deliberately withhold supply to boost prices), its molecules would be quickly replaced by others. Not only would Gazprom fail to boost prices, but it would also lose market share.

Even if Russia sells very large volumes to the EU, it cannot manipulate the market, because of competition

The strength of US LNG lies precisely in its flexibility, and in the fact that it is a key enabler of LNG commoditization – the process whereby the LNG market is on track to becoming a deep, liquid market with a lot of traders. This is supposed to reduce market manipulation by oligopolists, ‘de-politicise’ gas trade and further help a de-linkage of gas prices from oil prices.

Resurgent energy mercantilism

Yet, there are attempts in Washington to politicise US LNG, which has been rebranded ‘freedom gas’. The new mercantilist approach of the US government aims to push US LNG into the EU. This is one of the objectives behind US sanctions against Nord Stream 2: the US wants to promote sales of its own gas in the EU by reducing the space for Russian gas. This is done to strengthen the position of US industry, but also to hurt Russia economically.

President Trump condemned Germany for supporting Nord Stream 2. Photo Flickr.com

President Trump condemned Germany for supporting Nord Stream 2. Photo Flickr.com

President Trump explicitly condemned Germany for supporting Nord Stream 2 and importing Russian gas. He lamented that Germany enriches Russia, a hostile country that threatens German and European security, while the bill for security has to be paid (mostly) by the US.

Trump wants to strengthen the position of US industry and hurt Russia

After all, the US never liked the strong trade interdependence between Europe and Russia, since the deals in the 1970s that allowed Europe to get Russian gas in exchange for high quality steel pipes. It is important indeed to highlight that what we see between the EU and Russia is inter-dependence, not a one-way dependence as it is sometimes thought in the EU. Russia needs European gas buyers as much as (and arguably, even more than) Europe needs Russian gas supplies.While the EU imports 40% of its gas supplies from Russia, Russia exports around 70% of its gas to the EU.Gas sales to the EU are 8% of Russia’s total export value and 1.6% of the EU’s total import value.

This mercantilist strategy by the US government is unlikely to work: apart from Poland and Lithuania, as mentioned, EU countries do not seem interested in paying political premiums to discriminate gas by its origin. If, as is widely expected (and already happening), gas demand in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East grows strongly and alternatives are hard to come by, US LNG will go there.

Russia needs European gas buyers as much as Europe needs Russian gas supplies

A caveat to this is that trade wars can influence market-driven flows. Before the latest US-China trade compromise in January, China imposed tariffs on US LNG in retaliation of US tariffs on Chinese goods. Substantial flows of US LNG were then rerouted to other countries (including, as highlighted above, the EU). It is difficult to foresee what will happen in future, but what happened recently gave us a tasting of how politics could influence LNG markets.

A ‘smaller’ world with rampant protectionism could be dangerous for the EU, which is reluctant to enter new long-term contracts and relies on openness.

Long term gas relation EU-Russia

The EU and Russia still have a very strong gas relation. Russian gas is now being sold to Europe under market terms. Gazprom is a price-taker, lacking the ability to manipulate prices and to make a political use of its gas supplies. Competition between Russian gas and LNG is great for Europe, because it boosts both affordability and security of supply. One of the most thorny issues, Ukraine transit, has been resolved after painstaking negotiations. External interference from the US and new EU legislation are going to delay the construction of Nord Stream 2, but the pipeline will eventually be built, whether we like it or not.

Alexei Miller (left), CEO of Gazprom at a meeting with French politician Francois Fillon, november 2019. Photo Gazprom

Alexei Miller (left), CEO of Gazprom at a meeting with French politician Francois Fillon, november 2019. Photo Gazprom

Europe will continue to import a lot of gas this decade, because European gas production is falling but consumption is not, since gas will have to replace coal and nuclear that are being phased out in some countries. Europe will import flexible LNG whenever it will be available at a competitive price, i.e. when supply will be abundant and emerging markets will not absorb it all. US mercantilist initiatives to push ‘freedom gas’ will probably have a limited impact on flows.

Plans to exploit East Mediterranean or Caspian gas are interesting, but complicated by geopolitics and by the fact that very few European players are now in a position to sign long-term contracts or commit to massive capital investments in fossil fuels to supply Europe specifically. Furthermore, historical pipeline suppliers such as Algeria and Norway cannot increase their exports to Europe. This means that, in spite of political pressures to do otherwise, Europe will continue to import quite a lot of Russian gas, even beyond what is contractually obliged to buy.

In the meantime, it would be wise for Russia to diversify both its economy (away from fossil fuels) and fossil fuel exports, capturing opportunities in Asian markets and LNG. Moreover, it will be useful for Europe and Russia to boost the dialogue on how to redefine future relations in a deeply decarbonised world. Russia needs to understand that, if it wants to keep strong economic ties with Europe, it needs to develop the ability to offer clean molecules. Europe needs to understand that an economically successful Russia and deep trade ties are important for European security.

EU-Russia relations would have been even worse if it hadn’t been for deep trade interdependence fuelled by energy

This is perhaps a bold proposition at a time when nationalism, autarkic temptations and fragmentation are on the rise. To be sure, EU-Russia relations could be better, but they could have been even worse if it hadn’t been for deep trade interdependence fuelled by energy.

In the broader context, we are witnessing to a growing politicisation of energy, after a phase in which markets seemed to rule. Green energy is not exempt from politicisation. It would therefore be naïve to think that Russian gas is Europe’s energy security core problem and that once it’s out of the picture Europe will afford to stop caring about security of supply and thrive in a liberal win-win ideal world.

Luca Franza is Head of Energy, Climate and Resources at IAI (Istituto Affari Internazionali), and Research Fellow at CIEP (Clingendael International Energy Programme)