The birthday of KGB chief and shortlived General Secretary of the CPSU Yuri Andropov, on June 15, tempted many Russian commentators to muse on the question: what if he had not passed away in 1984? Our columnist Mark Galeotti shares his thoughts about the ruthless ideologue, who is an example for Putin but certainly would not have condoned the state of affairs in nowadays Russia.

Secretary General Yuri Andropov, example for authoritarians and libertarians alike (picture free of rights)

Secretary General Yuri Andropov, example for authoritarians and libertarians alike (picture free of rights)

On 15 June Russians – or at least certain particular varieties of Russians – celebrated the posthumous birthday of Yuri Andropov, some 36 years after his death. The KGB chief who became General Secretary, the man who sent dissidents into psychiatric hospitals but promoted Mikhail Gorbachev and the other 'young reformers', Andropov has become something of an icon for today’s new authoritarians.

Vladimir Putin certainly counts himself among them. As prime minister, he restored the plaque commemorating Andropov’s stint as KGB chairman to the wall of the infamous Lubyanka, and during his presidency, a statue to the man was erected in Petrozavodsk, where he had worked during the Second World War. In Putin’s words, he was 'a man of talent with great abilities', known for his 'honesty and rectitude'.

The Maybe-Man

The fact that Andropov suffered total kidney failure just three months after becoming General Secretary, and would die a year later, has allowed him to become the maybe-man, a figure assessed on his potential rather than his record. This, as much as his personal characteristics, may help explain his lasting appeal to certain Russians, as they place their own what-ifs and could-have-beens like wreaths on his grave.

An assessment in the mass market Komsomolskaya Pravda, for example, calls him 'the man who tried'. But tried to do what? 'Everyone who still remembers the General Secretary sees in him an unfulfilled dream.'

Above all, there is the notion that he could have been a home-grown hybrid of Pinochet and Deng Xiaoping, an economic reformer and political strongman. With that, the daydreams go, maybe the USSR would still be in existence, but in any case Russia would have a thriving, dynamic economy and avoided the anarchy and fragmentation of Gorbachev and Yeltsin.

Of course, the Soviet Union was not China, and the scope for a Chinese-style economic miracle pretty limited. Andropov certainly assembled an informal team of liberal economists, but whether it would have been possible to combine market-driven reform and political consolidation is hard to believe.

Given the extent to which the essence of Putin’s economic programme has been precisely to do that, though, it is easy to see why he affects to revere Andropov. After all, while Russia is notionally capitalist and democratic, political control permeates the entire system. Small-scale enterprise is largely left alone, but the 'commanding heights' of the economy are, even when officially in wholly private hands, still very much subject to the authority of the state. If you want to know who wins when they clash, ask Mikhail Khodorkovsky. (Who, incidentally, has expressed some positive views on Andropov.)

Likewise, although Russian democracy is by no means a total sham, nonetheless there is no question that it poses a serious check on the executive. Just ask Alexei Navalny.

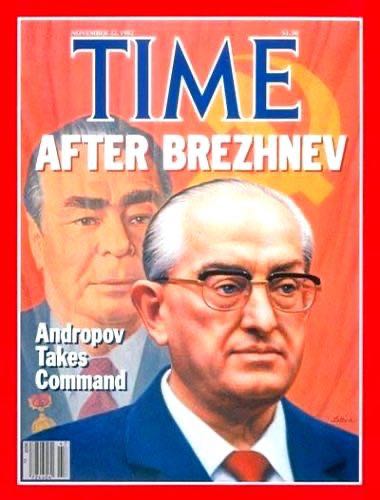

Andropov behind Secretary General Leonid Brezhnev

Andropov behind Secretary General Leonid Brezhnev

Andropov the ascetic

However, Putin’s own Andropov is a very convenient one, re-imagined as some kind of direct spiritual forebear. Andropov the cerebral and ruthless KGB chief – not Andropov, the man without whom Gorbachev would never had got to power.

After all, whether or not Andropov himself would recognise this descent is rather more questionable.

First of all, Andropov was an ascetic and a believer. Even amidst the complacent corruption of late Brezhnevism, he was a workaholic of simple tastes. For 16 years he and his wife lived in the same flat on Kutuzovsky Prospekt – a sizeable one by Soviet standards, to be sure, but austere and minimalist by the self-indulgent standards of his peers. Interior Minister Nikolai Shchelokov, for example, had an opulently-decorated full-floor apartment in the same building.

Shchelokov, as corrupt an official as one could find in that administration, was something of a personal bête noire of Andropov’s, and he would be sacked and disciplined for his abuses as soon as he became General Secretary, and would go on to commit suicide.

After all, Andropov’s notions of discipline extended beyond the crack-down on the black market and the police raids to catch workers taking unauthorised breaks. Although there was an inevitable degree of political self-interest at work as he purged Brezhnevite cadres, nonetheless Andropov also went after the worst of the embezzlers and bribe-takers at the top of the system, too.

What would he make of the gilded lifestyles of Putin and his cronies?

Andropov the ideologue

Andropov also had a phrase: 'you, of course, are a Communist, but not a Bolshevik'. It was not enough to have a red Party card and lard your speeches with quotes from Marx and Lenin, you had to believe. For Andropov, the cause of Soviet power was not a national one but an ideological one.

He had no hesitation about the use of force, whether orchestrating the brutal suppression of dissidents at home, or playing his part in the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. Ultimately, though, this was driven by his vision of the needs of Soviet power and its ideological mission. The same considerations drove his stance on the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan – but also the way he opposed military intervention by Soviet forces in Poland in 1981.

What would he have made of Putin’s exaltation of nationalism as the central pillar of his regime?

Ironically, the very strength of his Marxist-Leninist commitment meant that Andropov was well-known both for demanding the facts rather than sugar-coated reassurances and for being willing to engage with people who might have different perspectives. It was not just a practical matter – better to work off the realities on the ground – but at the same time a reflection of a degree of intellectual but also ideological self-confidence.

What would he make of Putin’s increasing dependence on a chorus of yes-men and the growing exclusion of alternative voices and facts that contradict his assumptions?

Waiting for Andropov 2.0?

Within the biting canon of Soviet anekdoty, political jokes, there was a small subset of what one might call Bolshevik anti-Sovietism. The grandmother being proudly shown around the palatial dacha of her careerist apparatchik grandson, eventually saying 'it’s lovely – but what if the Reds come?' Lenin awakening in his mausoleum, looking around him, and heading back to exile in Switzerland to await the next chance for revolution.

In that vein, one cannot help but wonder what Andropov would think of his self-proclaimed disciplines today, and whether he’d think he was back in late Brezhnevism.

Andropov was a product of his time, and it is hard to see any Andropov 2.0 having any relevance today. Nonetheless, what is interesting is precisely that Putin is vulnerable on this particular flank, too. It is not only liberals who can articulate an alternative vision for Russia, there are also critiques coming from the nationalist and traditional-leftist camps.

It is possible to use an Andropovian critique to damn Putin’s regime as much for its self-delusory muddle as its corruption. Beyond that, in theory, another reinvention of Andropov, the strong-handed reformer and anti-corruption strongman, could yet emerge as a political icon which would bridge many of the constituencies opposed to the current Kremlin.