The average Russian may not be happy with the state of affair, but he still fears one thing above all: that a change in political regime might only make things worse. However, youngsters have totally different values and attitudes. Will the next generation change Russia or is that just wishful thinking, wonders political analyst Andrei Kolesnikov of Carnegie Moscow Center.

Nurses in Vladimir demand better payment and protection because of covid-19. Screenshot YouTube

Nurses in Vladimir demand better payment and protection because of covid-19. Screenshot YouTube

by Andrei Kolesnikov

The average Russian is not happy with the state of affairs in their country, but that feeling of discontent doesn’t spur them to join the opposition or civil society. On the contrary, they feel annoyed when opposition leader Alexei Navalny or anyone else challenges their worldview, to the extent that passive conformism sometimes turns into an aggressive rejection of all the sections of society opposed to the government.

Since the last presidential election in 2018, only two events have dented the approval and trust ratings of the Russian authorities, personified by President Vladimir Putin: the raising of the retirement age and the pandemic. Back in April 2018, immediately after the presidential election, Putin’s approval rating was a mighty 82 percent. By July that year, following the unpopular move to increase the retirement age, that figure had fallen to 67 percent.

The majority didn’t mind that voting for Putin in the election was a mere formality. But they were outraged by the violation of the unwritten social contract: we vote for you, and you in turn deliver (and don’t take away) basic social benefits—which included the old pensions model. The social benefits inherited from the Soviet era are sacred for the post-Soviet Russian. This was evident back in 2004, when protests broke out over a government initiative to monetize social benefits such as free travel on public transport for pensioners.

Putin's rating

The pandemic, as a previously unimaginable force majeure, was not covered by the social contract. It frightened and angered people, causing Putin’s approval rating to fall to 59 percent in April 2020. In the summer, following the campaign to change the constitution to allow Putin to remain in power and the end of the first wave of the pandemic, his ratings went up again, settling at 65 percent during the second wave, which is about where they were in spring 2019.

In other words, what impacts most on the vast majority of Russians’ attitudes to the government is their psychological and emotional state. The most important thing is not economic and social indexes—most Russians have already gotten used to those deteriorating since the annexation of Crimea—so much as strong emotions: resentment of the authorities in 2018, and irritation at the overall situation, and therefore Putin too, in the spring of 2020. The connection with economic woes is indirect, nor is the link with politics clearly defined.

Increased dependency on the state

From 2018 onward, the mobilizing effect of propaganda surrounding the standoff with the West has no longer been sufficient to rouse people from their depression. Nor, however, are the political messages of the opposition enough to shake up most ordinary Russians, whose attention is focused on surviving, and who don’t see any alternative to the current regime for social support. As people become increasingly dependent on the state for money and jobs, the average Russian still fears one thing above all: that a change in political regime might only make things worse.

Older generations fear change, younger generations want change. Graphic: Wikimedia commons

Older generations fear change, younger generations want change. Graphic: Wikimedia commons

The pandemic has increased people’s dependency on the state even further, in addition to the existing trend of the state’s growing role in the Russian economy. This is clearly reflected in the structure of falling real incomes: according to the state statistics service Rosstat, the proportion of income derived from entrepreneurial activity decreased from 15.4 percent in 2000 to just 5.2 percent in 2020. The proportion of people’s income made up of social payments grew in that same period from 13.8 percent to 20.1 percent, meaning it’s now higher than it was during the Soviet period (16.3 percent in 1985).

The main thing for the regime is to maintain a feeling of unity and solidarity around the Kremlin, to avoid local centers of alternative thinking and action springing up. Events such as the delayed celebrations last year of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Soviet victory in World War II are useful and highly effective at boosting that sense of unity.

Increasing people’s dependence on the state also works to promote loyalty, as does focusing people’s efforts on survival—as opposed to 'post-materialistic' values such as human rights and freedoms—and on traditional conservative values at the same time. Research from the end of last year showed that given a choice between two sets of values, 62.8 percent of respondents believed that 'patriotism, following traditions, and keeping faith' were more important than 'civil rights, tolerance of other viewpoints, and equal opportunities,' which were prioritized by 37.2 percent. The same research revealed that just 14.4 percent were worried by the repression of rights and freedoms, while 54 percent of respondents were concerned by worsening poverty.

These paternalistic tenets are best reflected by the answers to the question 'What could lead to change in the country?' to which by far the most popular answer—selected by 47.5 percent—was 'a new, strong leader who would show the way.' But until there is a new leader, the average Russian is content with the old one.

As Mikhail Dmitriev and Anastasia Nikolskaya, the authors of that research, note, 'the intensity of the values conflict between the political elite and society, which had grown before the start of 2020, is once again declining, while the tension between society and the political elite has switched focus from values to a psychological and emotional dimension, most likely similar to that seen in the period of crisis that came at the end of the 1990s.'

Obedient youngsters needed

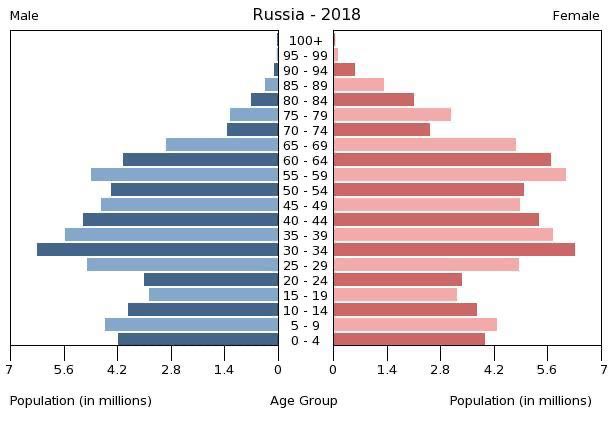

The demographic structure of Russia’s aging population means that in the coming years, it’s the older age groups who will determine the results of elections (according to Rosstat, as of January 1, 2020, one in four Russians—36.6 million people—was a pensioner).

So far, the Kremlin is winning the battle for the average Russian, who can still be mobilized in favor of the government. The impoverished and aging population depends on the state, and is largely controllable: their political loyalty can be bought with social aid (there are always resources available for that) in the run-up to the election, or at a time of economic crisis.

Military patriotic education.Photo: yunarmy.ru

Military patriotic education.Photo: yunarmy.ru

Judging by the move to reset the clock on presidential terms, the current regime has no intention of going anywhere for another fifteen years at least, so obedient younger voters will soon be needed, too. Given that the younger cohort may be more civically and politically active, the authorities are starting the fight to win them over, including by competing with Navalny. Their primary tactic is mirroring: for example, if volunteer activists take to the streets in protest, the Kremlin starts spurring on the rival volunteer movements under its own control.

The battle for the hearts and minds of Russia’s youth will not be easy: all the sociological data indicate that the younger age groups hold completely opposing views of current events—including the protests—to Russians aged fifty-five and over. This leads on to the key question of the third and final part in this sociological series: will the next generation change Russia and its political and economic priorities, or is that just wishful thinking?

This article was published originally by the Carnegie Moscow Center