On September 19 Russia sees Duma elections. In fear of a (far fetched) Belarusian scenario and angered by Navalny's challenge the Kremlin decided to crack down on all forms of independant political activities and journalism. The picture is bleak. But our columnist Mark Galeotti argues that the Kremlin will not be able to eradicate all forms of opposition. Don't underestimate the resilience of the Russians.

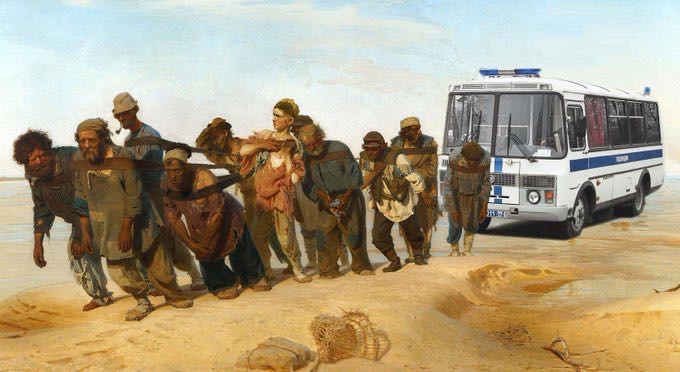

Meme on the Russian internet, mimicking the recent repression by a parody with a police van on Ilya Repin's famous painting Volga Boatmen

Meme on the Russian internet, mimicking the recent repression by a parody with a police van on Ilya Repin's famous painting Volga Boatmen

by Mark Galeotti

It is certainly hard to be cheerful about Russian politics these days. Alexei Navalny is languishing in labour camp Pokrov IK-2, and his movement is being systematically dismantled, labelled – libelled – as extremist. Remaining independent media outlets are being muzzled or closed down, not least as ‘foreign agents.’

Newssite VTimes is gone, and while Meduza is still hanging on, it has discovered that even moving abroad [to Riga] does not necessarily protect from the Kremlin’s wrath. Civil society is under assault, and even educational connections with the outside world are under attack, with America’s Bard College registered as an ‘undesirable foreign organisation,’ that ‘represents a threat to the constitutional order and security of the Russian Federation.’ (One can only wonder how vulnerable the Russian state must be, if a small liberal arts college in upstate New York represents an existential challenge to it.) The shuttering of the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences, an independent joint venture between Bard and St Petersburg State University, seems inevitable.

The new authoritarianism

Parallels abound, from Stalin’s Terror to the ‘North Koreanization’ of modern Russia. While perhaps understandable, we ought to take them with caution. There are no mass executions and even the recent decision to use prison labour on the BAM railway, admittedly an unfortunate echo of the Stalinist era, is not the same. Nor is Russia going to become another ‘hermit kingdom’ – its economy, culture and attitudes are too tightly enmeshed with the outside world’s. Such comparisons caricature rather than explain.

Instead, this is something much more simple, the response of an ageing yet ruthless kleptocratic elite to a perceived political challenge that some genuinely believe is directed as well as supported from abroad, and others simply affect to, in order to rationalise their repression. The poisoning of Navalny last year was a tipping point, but when he returned and his arrest sparked nation-wide protests, it seems a decision was made comprehensively to clear the board ahead of September’s Duma elections.

It is the response of an ageing yet ruthless kleptocratic elite to a perceived political challenge

No more piecemeal actions against an individual here, a local group there. No more willingness to entertain limited open dissent in the name of the appearance of democracy. Surkovian improv had long since given way to scripted drama; now, it was to be a monologue.

Yet it is too soon to be writing the obituaries for real politics in Russia. Not least, to do so is to under-estimate Russians themselves and the processes which have been reshaping the country since the 1980s, as well as to buy into the triumphant narrative of the Kremlin and its armies of thugs, informants, investigators and propagandists. Winter may be coming, but for now, it’s summer, so it is perhaps worth considering some of the ways in which meaningful politics and thus hope and democratic capacity survives in Russia.

Navalny’s movement, the Foundation Against Corruption (FBK) and his network of local Team Navalny headquarters, is dead. Indeed, this is no doubt one of the reasons for the escalation in the state’s response, as he was in effect creating a nationwide political party, even if one which could not register and fight elections in its own name. More than the Smart Voting campaign that sought to maximise the chances of United Russia candidates losing elections, it was this institutionalisation of opposition that made Navalny different and dangerous.

It was the institutionalisation of opposition that made Navalny different and dangerous

The Coalition of the Fed-Up

While the structure is being broken apart with enthusiastic zeal by the security apparatus, the passions and dissatisfactions which gave it strength have not. The inchoate ‘Coalition of the Fed-Up,’ the Koalitsiya Zadolbannykh, is still alive and capable of kicking. If Navalny is not able to harness it, someone else may. The Kremlin’s political technologists, marshalled by first deputy head of the Presidential Administration Sergei Kirienko, are also out to reshape the so-called ‘systemic opposition,’ precisely to make it more systemic and less opposition.

Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the increasingly erratic head of the nationalist Liberal Democrats (LDPR), is widely expected to leave active politics after September’s elections. Whoever replaces him will likely be a rather more pliable figure, given that the LDPR is essentially a bought and paid-for Kremlin project, there safely to soak up the protest votes of those who are unhappy with United Russia, but not unhappy enough to swing towards real opposition.

Gennady Zyuganov, the Communists’ answer to the folkloric Koshchei Bessmertny, ‘Koshchei the Undying,’ nonetheless may also be nearing the end of his political life, at least. He too is widely expected to step down after September, to a senatorial seat if he is lucky, a retirement tending his bees if not. However, the Presidential Administration seems to have the Communist Party (KPRF) in its sights, not least as too many in the next generation of potential leaders, as well as within the regional rank-and-file, actually think that an opposition party ought sometimes to oppose.

The newly-merged A Just Russia-Patriots-For Truth (SRZP) bloc is being lined up as a rival to the KPRF, either to replace or simply undermine it. Although it has only 23 representatives in the 450-seat State Duma at present (all from A Just Russia), there are suspicions it will overtake the KPRF and maybe even the LDPR in September. Writer Zakhar Prilepin, head of For Truth, even offered the KPRF an alliance of left-wing forces.

Reshuffling the systemic opposition parties forestalls the risk of the KPRF being both hijacked by a new, bolshy generation and holding a substantial stake in the Duma. It makes life easier for those such as Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin charged with managing parliamentary business. But it is unlikely to do much to harness, much less mollify the ‘Coalition of the Fed-Up.’ Prime minister Mishustin’s government is putting money and more money into trying to achieve at least a portion of the much-hyped National Projects, and there will be substantial give-aways to target social groups before September, but there are not going to be the 2000s-style improvements in quality of life that will remake the old ‘stay out of politics and enjoy the ride’ social contract.

Those disaffected, disillusioned and disgruntled Russians will still be there. Maybe someone else will give them an excuse to protest, whether someone outside the system as Navalny was, or even an insider. Firebrand writer Prilepin, former OMON, National Bolshevik and Donbas commander, now head of For Truth, may yet be an uncomfortable partner for Kirienko and Volodin. The coalition will be waiting.

The Belarus crisis erupted precisely because of the disconnect between the people’s sense of the result and the official outcome

After all, however managed, rigged and bypassed, elections still count. They are a referendum on the regime, and thus Putin himself, and the more sweeteners and propaganda has to be dispensed beforehand, and the more the results have to be rigged on the days, the less legitimate the look. It is not as though the Kremlin is going to lose the elections, but the ‘coalition’ may also simply refuse to vote, in itself a challenge. The political technologists are, after all, keenly aware that the Belarus crisis erupted precisely because there was too great a disconnect between the people’s organic sense of the result and the outcome announced by the state.

The original Repin painting of the Volga Boatmen

The original Repin painting of the Volga Boatmen

Dissidents

Votes and polls still count, then, even if just in making the regime work for its supermajority. Some of those who supported Navalny but now have no stomach for electoral politics will simply withdraw from politics, focus on making the best of it. This is, after all, a familiar route for Russians for decades and centuries. But others will take another well-trodden path, instead become dissidents.

There is room for all kinds of semantic debate about the term, but while there will continue to be those willing to stand as independent political candidates, in broad terms dissidents are often defined not so much by their active and direct opposition to the regime as their moral and ideological refusal to conform.

There are all kinds of ways in which such dissent can manifest, and in the modern, online world, the role of the individual can be magnified. Despite the government’s attempts to control social media, this is going to be a constant arms race of imagination and capacity, with new platforms and new ways of using old platforms to provide connectivity, relevance and solidarity to the new dissidents.

Others will stay in the bounds of civil society. Russian civil society has proven surprisingly resilient and resourceful, accepting the rules of the game – pretending that their goal is wholly specific and local, and not in any way a critique of the Kremlin or the wider political system – and have chalked up successes on everything from environmental issues to labour rights, despite the odds being stacked so heavily against them.

Even local civil society is also coming under pressure, but if the Kremlin is going to try and ‘nationalise’ it, it will have to address its concerns. For some, after all, elections and local activism are crucial in their own right. To most, they are means to an end, a way of communicating the ideals and needs of constituencies to their governments. If the Kremlin hopes to defuse and control mass dissatisfactions without giving them a meaningful political voice, it will have to be by finding out what its people want and providing at least some of it. Polls conducted by the Federal Protection Service (FSO), petitions collected before Putin’s ‘Direct Line’ telethon, concerns expressed by local mayors and governors trying to avoid local infamy, all these perversely substitute for part of the practical work of democracy.

Putinism from below

There is unlikely to be any substantive improvement in the situation, certainly so long as Putin remains in the Kremlin. Navalny’s poisoning and the subsequent crackdown represents a watershed moment. The best Russia can hope for is that, if its repressions help the Kremlin organise the kind of outcome in September that allow it to feel more confident, there will then be something of a deceleration. Navalny will probably remain in prison and generally there will likely be no reversal of past vindictiveness but rather no urge for more: deceleration, not reverse.

Of course, the danger is then of ‘Putinism from below,’ that unless the Kremlin gives very clear and unambiguous signals of the new mood (which it may well not, based on past experience), that the security agencies as a whole and local commanders in particular may continue the repressions, assuming that it is still the Kremlin’s will, or simply because flexing their muscles also helps their political status and can be used as an excuse for extortion and ‘raiding’ businesses.

Nonetheless, the dissident movement, samizdat literature, artistic and cultural resistance and above all hope all managed to survive in the Soviet Union, in the face of a regime which was much more brutal, capable and ideological than we see in today’s Russia – and tomorrow’s, too. While deploring the new repressions, we should not buy the notion that resistance is futile, and that Russians are no more than the hapless and helpless victims of their state.