From 10 till 15 September Russian and Belarusian troops held their joint military exercises Zapad-2021. Strangely enough, notes expert Hannes Adomeit, the main push was directed not against the West, but against Ukraine. To the chagrin of Lukashenka Putin didn't even come to Belarus, but watched the maneuvers in Mulino, near Nizhni Novgorod. For an explanation Adomeit points to the 'spontaneous' drills near the Ukrainian border, last spring, that send shivers through Kyiv. How to read these messages of combat readiness?

Russian troops in Mulino preparing for Zapad-2021 (picture Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Russian troops in Mulino preparing for Zapad-2021 (picture Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

On 15 September the Russian defense ministry concluded Zapad-2021. The maneuver was the largest in the series of operational-strategic maneuvers conducted every four years by the Russian armed forces together with Belarus and a more or less symbolic sprinkling of units from other countries. Zapad in Russian means ‘west’. Correspondingly, the maneuvers under this heading are held in the Western Strategic Direction − one of four, the others being the Eastern and the Central Strategic Direction, and the Caucasus.

Like all the strategic maneuvers, Zapad-2021 was meant to achieve multiple purposes, including the further development of operational concepts, experimenting with force structure, testing new weapons systems, and improving the cooperation between military and civilian entities, logistics and the mobilization of reserves.

This year, however, the maneuver differed from its predecessors in a number of important respects. This was due in part to the changed geopolitical circumstances, notably the severe domestic political crisis in Belarus. This led to special emphasis given to military cooperation between Russia and Belarus; their military, as well as economic and political integration; and interoperability between the armed forces of the defense ministries and the internal security and secret services in and between the two countries. These aspects were made explicit and were evident in the extensive prepositioning and practices in July and August in Belarus prior to the main event. Yet another, if not the main purpose of Zapad-2021, however, as will be shown, was connected with Ukraine.

Size, deployments and scenarios

According to the Russian and Belarusian defense ministries, the military exercises began simultaneously on 10 September at nine Russian locations from the Baltic Sea to the Voronezh and Nizhny Novgorod regions as well as at five Belarusian locations. Simulated fighting with thousands of soldiers equipped with heavy weaponry also took place in the border areas to Norway and Finland on the Kola Peninsula. The exercises were led by Russia’s Western Military District’s Joint Strategic Command in close cooperation and coordination with the Northern Fleet’s Joint Strategic Command.

VDV’s 137th Airborne Regiment loading up BMD-4M armored vehicles onto Il-76 transport aircraft at the Dyagilevo airfield in Ryazan. The aircraft will fly to the Ulyanovsk-Vostochny airfield before dropping the paratroopers and equipment.

VDV’s 137th Airborne Regiment loading up BMD-4M armored vehicles onto Il-76 transport aircraft at the Dyagilevo airfield in Ryazan. The aircraft will fly to the Ulyanovsk-Vostochny airfield before dropping the paratroopers and equipment.

A total of 200,000 troops, over 80 aircraft and helicopters, up to 760 units of military equipment, including tanks, rocket launchers and mortars, and up to 15 ships were said to have been involved. Of these, 12,800 were scheduled to take part in the exercises in Belarus, including up to 2,500 Russian military personnel, more than 30 aircraft and helicopters, up to 350 units of military equipment, including about 140 tanks, up to 110 guns, multiple missiles and mortars.

The 200,000 figure, according to Michael Kofman, is probably grossly exaggerated. A good guide to numbers may be ex post facto assessments by Western military experts of the Zapad-2017 exercise, a ballpark figure being about 50,000 troops. The number inflation for the 2021 maneuver is reflected, among other indicators, by the discrepancy between the high number of troops and the low number of weaponry and military equipment provided to them. Unless the figure for the total number of soldiers was simply pulled out of a hat, it may be due to the Russian defense ministry having counted personnel from other participating security institutions. These included the interior ministry (MVD), the FSB border service and Rosgvardiya, the Russian National Guard.

The last named organization is of special interest in the present context. It held its own drills named Zaslon (barrier) in July 2021 to exercise the suppression of ‘terrorist’ activities which, in the framework of Zapad-2021, could have meant the quelling of internal unrest and the elimination of ‘diversionary’ activities by the enemy coalition on Belarusian soil. Indeed, the maneuver posited the scenario of a further deterioration of the military and political situation in Europe, and having failed to destabilize Belarus through non-military means, a hostile coalition decided to use force to achieve its political aims.

Opening of Zapad-2021 drills (filmed by Sputnik Belarus)

Lukashenka: 'In 1941 we practically lost Belarus in a couple of months. History teaches a lot. We want to be prepared in advance, and that’s the essence of the present maneuvers.’

Credibility to this scenario was provided by Belarusian dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka on the Baranovichi training ground in western Belarus when he said that in 1941 there had been no response to provocations and ‘then [we] received a devastating blow and practically lost Belarus in a couple of months. History teaches a lot. We want to be prepared in advance, and that’s the essence of the present maneuvers.’

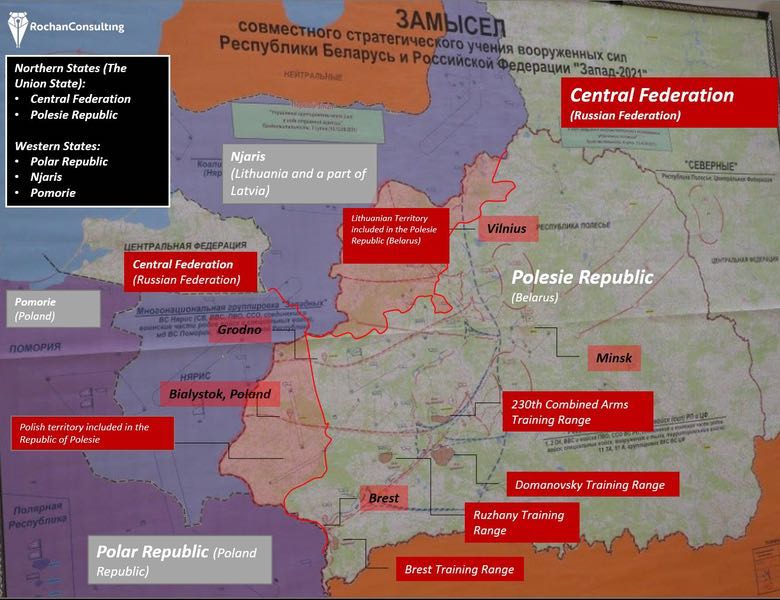

The fictitious hostile coalition of the Zapad-2021 war game comprised the states of Nyaris (Lithuania?), Pomoria (Poland?) and the Polar Republic (Norway?) along with so-called terrorist organizations. The task for the joint Russian-Belarusian forces was to compel the Western group of forces to terminate hostilities and withdraw. In line with this scenario, the exercise was conducted in two stages. In the first three days, Russian forces simulated the enemy’s military intervention and the joint Russian and Belarusian response.

Map of battle field Zapad-2021 (Rochan Consulting, on basis of Belarusian ministry of Defense)

Map of battle field Zapad-2021 (Rochan Consulting, on basis of Belarusian ministry of Defense)

In doing so, the friendly forces were not just defending but engaging in sustained counterattacks, seeking to disorganize and degrade the opponent’s offensive operation through conventional strikes and electronic warfare. The second phase involved a comprehensive combined-arms ‘counteroffensive’. A joint force of armor contingents of the Russian 1st Guards Tank Army and Belarusian units, Russian paratroopers, Russian combat aircraft and anti-aircraft missiles defeated and eventually pushed back the invaders from Belarusian soil.

The balance of power

In the run-up to and preparations for the Zapad-2017 maneuvers there had been some concern that the exercises were essentially a cover for actual military intervention in the Baltic area. The concern was in part based upon the vast discrepancies in military forces of Russia and NATO. Thus, the active duty forces of Russia’s Western Military District, including the Kaliningrad province and the Baltic Fleet, comprise three armies (the 1st and 20th guards and the 6th army), the 6th Air and Air Defense Forces Army, three of the four airborne divisions (the 76th in Pskov, the 98th in Ivanovo and the 106th in Tula) and two Spetsnaz brigades (the 16th and 322nd), in all totaling about 400,000 troops. Reinforcements were readily available from the Northern Fleet and the Central Military District.

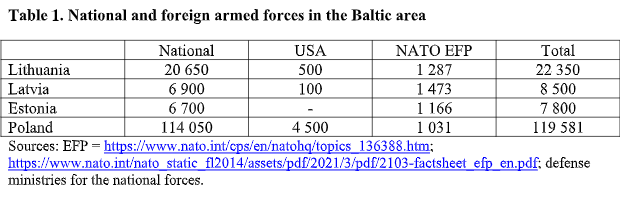

In contrast, the national and foreign forces of NATO countries in the Baltic States and Poland constitute only a fraction of the Russian military capabilities:

(Sources: EFP = nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics; nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/; defense ministries for the national forces)

According to Russian military analyst Pavel Felgenhauer, Lukashenka had apparently hoped that Zapad-2021 would demonstrate Belarus’s military and strategic importance and break the wall of Western ostracism. He had invited observers from NATO member states to monitor the maneuver but none came. Conspicuous for his absence was also Russian president Vladimir Putin − as was the top Russian military leadership. Moscow was represented only by a two-star general, Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, the former head of the southern Russian republic of Ingushetia and now a second-tier deputy defense minister in charge of battle-readiness training.The Ukrainian dimension

While Lukashenka was struggling to assert his relevance in Baranovichi, Putin was overseeing what was in all likelihood the more important and main event, over a thousand kilometers eastward, in the garrison and polygon town of Mulino in Nizhny Novgorod province. There, the highest Russian military leadership was present, together with thousands of soldiers and tanks. Also participating were a Belarusian army battalion and token contingents from Armenia, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia; staff officers from Uzbekistan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka; and a crowd of international and Russian journalists. The Western embassies in Moscow had at the beginning of September received a preliminary invitation for their military attachés to observe the maneuver in Mulino, but shortly thereafter it was withdrawn as a ‘mistake’. Thus, not a single NATO member state representative was able to observe the show.

New Russian weapons (graphic Izvestia)

Felgenhauer also points to a significant difference in the scale and the circumstances of Zapad-2021and the huge concentration and full mobilization of Russian armed forces in March and April of the same year to test their ‘combat readiness’. Russia’s first deputy defense minister and chief of the General Staff, Army General Valery Gerasimov, then told journalists that over 300,000 men, 35,000 pieces of heavy weapons, 180 ships and around 900 aircraft had been deployed. In comparison, the figures for weaponry of these deployments were 10-20 times higher than the official numbers for Zapad-2021. That is to say, if the number of weapons officially declared for the deployments of forces in the spring was more or less correct, there were several thousand or tens of thousands of men not included in the number of ‘over 300,000’ deployed close to Ukraine’s borders.

Why the discrepancies?

The discrepancies raise important questions. What may have been the purpose of the massive deployments? Why the facts that they occurred without prior warning; no foreign military or other observers were invited; and the entire operation was scantly reported by the Russian press? And why, on the other hand, were the smaller Zapad-2021 exercises in the Western Strategic Direction announced a year in advance, with extensive press tours organized for Western and other media?

This raises still other questions. Yuri Fedorov, another eminent Russian military specialist, has pointed out that the previous joint strategic exercises with Belarus were held in areas adjacent to the western borders of the Union State. For all the absurdity of the assumptions about a possible invasion of NATO troops into Belarus or Russia, this had its own logic: NATO in these countries was considered the main enemy.

But this year, the main part of the exercises took place not near the Russia-NATO contact line but, as noted, far from it, in the Voronezh and Nizhny Novgorod regions. It was also there that their culmination took place on 14 September; Putin observed them at the Mulino training ground; and the chief of the General Staff, General Anatoly Gerasimov, reported that about 20,000 personnel, 160 tanks, more than 100 aircraft and 100 helicopters had taken part. Such figures are much higher than those provided for the Belarusian war games part, where the personnel of the grouping of allied forces (as quoted above) were said to have numbered 12,800, of which 2,500 were Russian soldiers and officers.

Offensive operations against Ukraine

The conclusion to be drawn from the analysis by the two Russian military experts is that the main purpose of Zapad-2021 was connected less with defense against a NATO attack but with contingencies of offensive operations against Ukraine. This links up with the pattern of the Russian military deployments, the structure of forces and the systems of military hardware moved towards the Ukrainian borders in March-April which strongly suggested war gaming for an offensive operation rather defense.

Foreign troops in Mulino at the opening ceremony of Zapad-2021 (picture Russian Ministry of Defense)

Foreign troops in Mulino at the opening ceremony of Zapad-2021 (picture Russian Ministry of Defense)

Indeed, at the time it seemed that Russia was seriously considering another military intervention, perhaps to link up the separatist entities of Luhansk and Donetsk beyond Mariupol to the Crimea and perhaps even to revert to the Novorossiya project that Putin had advanced in April 2014. In retrospect, it appears motivated much more by yet another attempt to force Ukraine to comply with Russian demands and to dissuade European NATO member countries from delivering weapons and help strengthening of the Ukrainian defense potential.

Such assessments of both the Zapad-2021 and the March-April maneuvers are shared by Alexander Golts, yet another independent Russian military analyst. He notes that Russian defense minister Sergey Shoigu had then, in reference to the latter ‘combat readiness’ maneuvers, announced that two combined-arms armies and three airborne divisions had been deployed in the maneuver area. This, according to the analyst, was yet again a highly exaggerated claim. But whatever the true size of the still substantial forces, whereas the main bulk of the troops had returned to their permanent stationing areas, the weapons and equipment of the 41st combined-arms army belonging to the Central Military District were left behind at the Pogonovo training ground near Voronezh – evidently to be used in the Zapad-2021 strategic exercise.

A final piece of evidence testifying to the main purpose of Zapad-2021 was, as Felgenhauer reported, provided by Tatyana Shevtsova, the Russian deputy defense minister in charge of finances. She confirmed that during the exercise an ‘innovative’ scheme of troop financing through field offices of the state treasury, the Bank of Russia and commercial bank outlets, had been tested and that this system was intended to provide troops deployed in the field during wartime with money, ‘including rubles and foreign currency’.

Shevtsova did not spell out which foreign currencies would be provided. The implication of the present analysis, however, is that the foreign currency would more likely be Ukrainian hryvna rather than Belarusian rubles. The availability of the local currency, of course, would put the commanders of the interventionist force in a position to purchase supplies and pay for services of any kind for those who may be willing to provide them.