People in power, middle class business men who prospered under Putin, technocrats who are not allowed to leave: Yevgenia Albats, editor in chief of the Russian magazine The New Times, talked to scores of them since February 24, the day of the invasion. They are desperate and most speak only anonymously. They see their future in ruins, their money disappearing, their positions dwindle. Nobody had expected this turn of events. Everybody is scared.

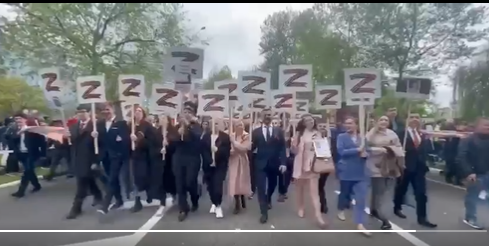

Victory Parade on May 9 in Sochi (picture twitter)

Victory Parade on May 9 in Sochi (picture twitter)

by Evgenia Albats

If there is any advantage to living in Moscow in these troubled times, it is the opportunity to meet with people in person. They prefer privately. Better in a restaurant with no one around. Or better yet in the corner of a small city park.

Even so, few people in power are willing to meet. They are afraid to even answer a message on an app let alone be seen in public. But there are exceptions. There are people who are retired, or who have known me for a long time, businessmen who yesterday had been in the security forces, or doctors, or acquaintances who suddenly discovered that they’d been robbed and tossed away despite their United Russia Party badges and long, impeccable service records.

Here is what we talked about. The quotes are real; the names are not.

The officials

Officials, they tell me, can be divided into clean and unclean. The clean ones are the guys in officers’ uniforms, mostly from the Federal Security Service (FSB). They make decisions, they punish, they are feared. Everyone else is unclean. But among them there are gradations. There is the 'run and fetch' crowd, now largely the ideologues in the presidential administration who 'get orders' from the FSB and carry them out.

The government's economic section has a special position today. Technocrats are in high demand because they are supposedly saving the economy from the endless stream of new sanctions. In actual fact, their task is hopeless. About 70% of goods manufactured in Russia have imported components, and it is impossible to replace them. There are endless meetings in the government, says a well-known financier and former high-ranking official. The director of a factory that makes Russian aircraft comes in. He’s got a problem: his engines are imported. He promises that he will build his own — if they give him money and lots of it. Then he can make it in two years — if he can make it. A financier tells me, 'I haven’t met anyone [in the economic section of the federal government] who supports it [the war in Ukraine]. They all know it’s a catastrophe. But they are all trying to figure out how to comply.'

'Where can I go?' says another top-ranking bureaucrat, also horrified by what is happening, and one of the few who is not yet under sanctions. 'They won’t let me leave.' You don’t need to be a mind reader to see that they are all trying to come up with a way to get out. '90% of them don’t like what is going on,' says a doctor in a private Moscow clinic about his patients who are government officials. 'Everyone is afraid to open their mouth — the example of Ulyukayev or Abyzov is before their eyes, so they adapt,' says a financier.

'Only the security forces knew about the start of the operation. Even [Prime Minister] Mishustin didn’t know, and neither did Elvira Nabiullina [governor of the Central Bank],' says a government official. 'During that famous televised Security Council meeting, it was clear that the most informed were against it,' says a retired secret service general. He thought the officials trying, however fearfully, to say that maybe this wasn’t the right time were Mikhail Mishutin; Nikolai Patrushev (Security Council Secretary); Dmitry Kozak (chief negotiator of the Minsk agreements); and Sergei Naryshkin (head of the Foreign Intelligence Service), whom Putin publicly humiliated.

The siloviki

No one can say for sure what goes on inside the corporation that controls the power in Russia — the FSB and its partners, commonly called the siloviki — but retired generals say there is no unity there either. Someone inside the Russian special services warned both the U.S. and Ukraine about preparations for the 'special operation'.

My contact told me, 'Maybe it’s not really a purge, but there is definitely an investigation going on — a political one, about treason.' No one has confirmed the rumors about nearly twenty generals being arrested. But there's talk of a conflict between the security and military officials, since someone has to become the scapegoat 'for the failed first stage of the operation,' says my source.

A young officer calls Putin 'Grandpa' and says it's time for him to retire. But first he threatens 'we can do it again' [go to Berlin again–YA] if these 'f***ers don't stop tormenting Russian children by throwing them out of boarding schools and universities.'

Putin at the Victory Parade at Red Square (picture Kremlin)

Putin at the Victory Parade at Red Square (picture Kremlin)

The young guys are very angry. Many have had their businesses collapse, their savings have been frozen in banks under sanctions, and they can no longer send their dirty money offshore. Because the movement of money, the cash market and other things related to finances are also controlled by the Chekists [security services], many of them had already invested in cryptocurrencies. But as a result of the sanctions, they were cut off from large cryptocurrency exchanges. On April 21, Binance stopped serving cryptocurrency wallets that were worth 10,000 euros and more and were registered to Russian passport holders.

Other platforms had already done the same. Many people had trouble sending money abroad and couldn’t keep up with mortgage payments on their foreign investment real estate. Of course, they came up with a way. Due to the sanctions, the country has a surplus of gold. You can only take $10,000 per person in cash out of the country, but you can take up to $70,000 worth of gold. So they buy gold bars and fly them to the Emirates. There a market of financial services is being developed to help clients avoid both the Russian Central Bank and Western sanctions.

The loyalists

'I was about to leave the [pro-Putin] United Russia party,' a former official I’ll call Kirill told me. 'What stopped you?' I asked. 'I got a phone call — they said, "Are you nuts? They’ll come and arrest you".'

Kirill is outraged: the war in Ukraine — or rather the sanctions imposed on Russian banks and companies — have ruined him completely. Or at least enough to hurt.

In 2019, Kirill told me, the Russian state called upon wealthy Russians to invest in the domestic economy. De-offshorization; the ban on travel abroad for millions of law enforcement officers, judges, prosecutors and other rent collectors; the need to launder corrupt earnings; and finally, the banal need for money, which, as we now know, went to manufacture hundreds of tanks, armored vehicles, aircraft, grads and other iron for the war in Ukraine — all this prompted economic authorities to develop mutual funds. They said, 'Hand over your money and be patriotic!'

All the main state and commercial banks opened mutual funds and attracted clients with Russian and foreign blue-chip stocks and high interest rates. Kirill told me that when savings were earning 3.4% interest rates, the mutual funds were returning 22%, and by the end of the summer of 2021 they even reached 27%. There was one inconvenience: the money had to be deposited for three years. If you withdrew earlier, you had to pay 13% in taxes. And although anyone could buy a small share in a mutual fund, it was profitable with a lot of money. 'It made sense to start with 10 million,' Kirill said.

According to the report of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, in 2021 7.7 million people had invested their money in these mutual funds. The net inflow of funds amounted to 989.5 billion rubles, and the amount invested was about 7 trillion rubles, give or take a few billion.

Then, on February 24, 2022, 'Kiev was bombed, and we were told that a war had begun.' First the Russian state banks were sanctioned and then the commercial banks. And in the blink of an eye, all those mutual funds with their trillions ceased to exist. That is, they exist, but in Russia there is no stock market, which means that the value of stocks is unknown, not to mention the fact that investments in foreign securities are simply frozen until the day after forever.

When Kirill went to VTB Bank, which managed his shares, he found out that the millions he had invested were gone. Right now, they are completely gone. Maybe in time, they will give back 40% of what he invested, or maybe they won't.

And there are more than 7 million people like Kirill in the country, Putin’s middle and upper class. Six months before disaster struck one of them told me, 'You and Navalny are tilting at windmills. We are the middle class, and everything suits us fine. Putin lets us earn money, and so what that there aren’t elections — you don’t make money off elections.' He had all the rest: children in private schools now and off to the best European universities later, holidays in Crimea and the Emirates three or four times a year, better restaurants than in Europe, clothing, luxury gated communities, etc. Who cares about elections when Chanel and Louis Vuitton make life worth living? Right?

While the Russians still have not conquered the Azovstal factory in Mariupol, a Victory Parade was staged nevertheless in the completely destroyed harbour city (picture twitter)

While the Russians still have not conquered the Azovstal factory in Mariupol, a Victory Parade was staged nevertheless in the completely destroyed harbour city (picture twitter)

None of the people I spoke with could formulate the idea or ideology that was the basis of their loyalty. They are all just opportunists who regarded support for the regime as a form of capital investment. They viewed Putin's aggressive rhetoric toward the West as the correct strategy: if a competitor cannot be beaten in business, then he must be crushed, broken, and forced to surrender.

But unlike the 1998 collapse, the current financial and economic crisis has no positive outlook. There is only one direction it can take: down. The bureaucrats, the siloviki, and the loyalists who have become (almost) an opposition still hope to reverse the negative trend.

I have no doubt that they are reading reports from the frontline in Ukraine very carefully. How quickly will they realize that the life they have built for themselves is over? That the old one will never come back? That politics came for them and now they will have to eat scraps from the sanctions? And that this disaster, which has destroyed their future and that of their children, has a first name and a last name?

These people may have different points of view, but so far I haven’t found anyone willing to sacrifice themselves for the cause of expanding the Russian Empire.

This was first published in Russian in The New Times. The English translation is from The Moscow Times.