Due to its own lack of reforms and decisiveness, Russia played second fiddle as a prime mover on oil markets for seventy years. The actual price hikes on the globale markets, a consequence of Russia's war in Ukaine, is hiding this subordinate position from view. But not for long, argues Nick Trickett. The sanctions on Russian oil will have an effect in the longer term. As Europe opts to look to the Middle East and across the Atlantic instead, it’s signed Russia’s death warrant as an oil power.

Oil refinery plant in Yaroslavl. Picture Wikimedia Commons

By Nick Trickett

As sanctions and self-sanctioning continue to hit Russia’s oil sector, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak forecasts oil production will decline 5−8 percent for 2022 despite short-term increases in output from March and April lows. These losses amount to 1.5−2 million barrels per day of exports. The Ministry of Economic Development is slightly more bearish; it expects 9−10%. Both may want to revise their thinking. Worsening the outlook is the latest EU sanctions package passed in a compromise deal on May 31.

The new package may not be the decisive blow to Russia’s oil and gas revenues that many wished for. But It is still hefty. Up to 90% of European imports of Russian crude are covered by agreements to phase them out by year end while allowing pipeline-dependent importers to continue to buy. All seaborne imports are banned. A Joint UK-EU move also bans insurance firms from insuring and reinsuring Russian crude shipments, threatening exports to non-European markets with a limited availability of experienced insurers confident of how to manage sanctions risks.

Even this watered-down import ban is a huge gamble for Europe. Eurozone inflation surpassed 8% year-on-year in May, about half of which can be attributed to energy and food. Brent crude is trading above $120 a barrel with every expectation that prices will continue to rise. Europe is committed to rewiring global flows of crude oil despite the economic pain. Russia cannot readily redirect all affected production elsewhere to offset these incoming losses. Nor can it maintain its geopolitical influence as an oil power at this rate.

Europe’s Energy Triangle

Europe’s dependence on Russian oil was shaped by geopolitics. The Suez crisis in 1956 triggered a shutdown of the canal. Overnight, the most important artery for the global oil trade was shut and Europe’s over-dependence on Middle East exports exposed. New sources were needed to avoid political disruptions and Soviet planners undergoing a significant output expansion in Western Siberia attempted to cut deals with Western European importers to undercut the de facto price monopoly power exercised by Anglo-American oil majors producing in the Gulf. Nasser’s closure of the Suez Canal from 1967−1975 and the Arab Oil embargo of 1972−73 further strengthened the importance of maintaining diverse sources of supply to reduce OPEC’s power as a cartel and ensure European energy security.

Thus, European energy security became enmeshed in a ‘triangle’ between the Soviet Union/Russia, Middle Eastern exporters, and the United States.

Soviet ‘oil power’ emerged in conditions of supply scarcity and political upheaval for European energy security as it could no longer rely on exports from the Americans or the stability of supplies from the Middle East to meet its growing needs. Yet the pursuit of political influence and hard currency earnings to cover the considerable food and technological import needs of the Soviet economy led to the gross mismanagement of the nation’s oil wealth. The oil sector became a massive vacuum sucking up capital that could have been deployed more efficiently elsewhere to help rebalance the economy. Fears of export leverage over NATO members were overcome in the 1980s by the rise of new sources of production in the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico, the Saudi decision to flood the market in 1986 to try and drive out higher cost producers, and the liberalization of global oil markets, including the de facto end of posted prices and launch of oil futures contracts.

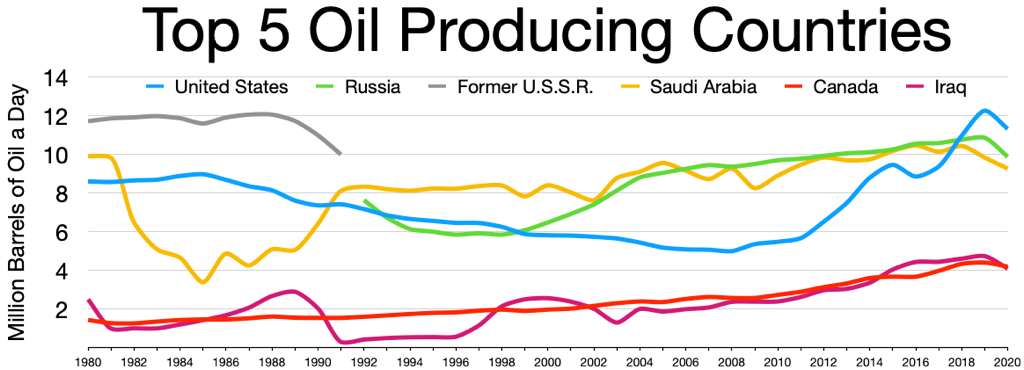

Since 2010, the 'oil triangle' between Russia, the Middle East, and United States shifted with the explosive growth of US output. Between 2010 and 2019, global oil production rose by approximately 13.5 million barrels per day (bpd) using BP’s data. US production accounted for 73% of that increase (9.8 million bpd), whereas Russian output growth matched just 11.3% (1.5 million bpd). The rise in Gulf production for the time period reached 43.4% of that total value (5.9 million bpd) with output declines elsewhere lowering offsetting these gains. US crude began to flood into European refineries by 2018 as Texas overtook Iraq in terms of total production, aided by US sanctions on Iran and, to a lesser extent, Venezuela.

European importers had more freedom to look elsewhere with prices broadly stabilized between $ 60−75 a barrel. European oil demand was comparatively weak, and thanks to a combination of post-financial crisis austerity policies, environmental standards, and the availability of mass transit and rail transport across the continent, demand in 2019 was still nearly 2 million barrels a day lower than 2006.

Pre-COVID was a buyer’s market globally, one where Russia systematically failed to adapt through a meaningful reform of the oil sector tax regime because of its centrality to the fiscal system. Between 2010 and 2019, output gains were primarily achieved through improved efficiency at depleting wells, horizontal drilling, and a hodgepodge of tax breaks awarded to Rosneft’s Soviet-era fields. Even MinEnergo warned in 2019 that production might begin falling by 2022 because of the tax regime and lack of greenfield investment. Output growth average barely more than 1% between 2010−2019.

Thanks to the new sanctions, it’s likely that we’ll see consistent year-on-year declines in Russian output in the next few years after a sharp drop in 2022 expanding from a 2−2.5 million bpd drop this year. Trader Trafigura holds 10% of Rosneft’s Vostok Oil, the only major greenfield left in Russia and driver of Rosneft’s upstream investments last year, but has decided to freeze all investment and exit the project. Even if firms swap European buyers with ones across the Asia-Pacific, they can’t fix this problem.

Clawing For Influence

The oil shock of 2014−2015 forced Russian policymakers to cooperate with Saudi Arabia and OPEC to stabilize prices, the budget, and offer a path out of a recession amid significantly elevated interest rates as the central bank sought to limit capital outflows. Russia had last done so in 1999 as it recovered from the financial crisis and domestic default of the previous year.

In agreeing to coordinate production cuts, the oil sector would be forced to constrain its investment into exploration and development to provide Russia an avenue to nudge oil markets. MinEnergo had first argued to limit Russian cuts to 300,000 barrels a day, but Putin reportedly agreed to larger cuts as needed after consulting then Iranian president Rouhani. The cumulative 2% reduction in global output was supposed to rebalance inventories over the next few years.

Markets adapted, reacting to this or that phone call between Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and other regional leaders. The limitations placed on the oil sector undermining greenfield development won the regime political capital to talk the market up or down as well as use cooperation on the oil market as a window to other deal-making.

Graphic Wikipedia

Coherent or not, the expansion of Russian activity across the Middle East that began with its intervention in Syria came to work in tandem with the Russian political system’s dependence on oil rents, amplifying concern and interest when Rosneft acquired assets in Iraqi Kurdistan and Russian mercenaries began to regularly appear in Libya. Politics trumped the economics and structure of the oil market.

Power over price stability and supply/demand balances depends on the capacity of a leading producer to extract oil cheaply, easily, and in response to marginal changes in demand and supply. This is the so-called role of a 'swing producer', the position Saudi Arabia has historically occupied given its ability to match all three of these criteria and maintain several million bpd of spare capacity to increase output in response to supply disruptions. Russia has never been capable of adroitly reacting to marginal increases in demand, let alone maintaining output under current conditions. It also couldn’t recreate this kind of market power from the barrel of a gun with a larger footprint in the Middle East.

Europe’s Gamble

Europe’s decision to wean itself off Russian oil is a conscious choice to depend on both the United States and Middle East exporters to a greater extent and accept greater economic pain in the short-term for the sake of security. It’s a bet that Russian policymakers have broadly dismissed as impractical and politically unviable for the last two decades. The new EU/UK oil sanctions are surprising because of the ways in which COVID has disrupted the market. Whereas the glut in 2020 worsened by Russia’s ill-fated price war ended up forcing an unprecedented 10 million bpd in coordinated output cuts led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, strong global recovery starting in 2Q 2021 led by the US economy created concerns about supply that were present by the end of last year. There isn’t a shortage of oil so much as constraints on refining capacity and curbs on Chinese refined products exports.

Goldman Sachs expected oil prices to reach and settle around $140 a barrel over the summer, but US consumers will experience prices closer to $160 a barrel because of how many refineries either reduced throughput, were slated for retirement, are under repair, or else had investment plans canceled due to the demand crash in 2020−2021. 2021 saw global refining capacity decline for the first time in 30 years. Through May this year, China’s refined products exports are down 38.5%. US production is set to post strong growth this year, just not enough to fully make up the shortfall. Nor will OPEC increases cover all of the losses from Russia.

Even if the long-term replacement of imports is quite feasible, it’s the short-term that’s so worrying. There is no plan in place to address refined products and crude oil prices and shortages. Doing so requires coordination between crude oil importers, namely China, and the companies in the United States that vociferously fight Democratic administrations over environmental regulations. Notably, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has stated that her team and department are in 'very active' talks about instituting a price cap on Russian crude oil exports to limit the potential gains in fiscal revenues and business profits from high prices. It also conveniently creates a mechanism to politically lower Russian export prices and strengthen the negotiating power of buyers outside of Europe and North America as new insurers and Russian schemes to self-insure crude oil cargoes attempt to fill the gap created by the new EU/UK bans. Consumers will assuredly feel the pain for the rest of the year regardless.

A New Era

The current regime’s play for geopolitical clout on the oil market was always rooted in financial needs and the comparative weaknesses of Russian production against the US and Saudi Arabia. Influence came from negotiating a stable price level, not from providing marginal barrels to meet new demand and its low production costs were buttressed by a continued reliance on western technology and know-how it can no longer import. Structural factors are also turning against any revival of Russian crude output in the future. Electric vehicles are currently the only growth market for net global vehicle sales. High gasoline prices are now punishing the millions of consumers in the US who opted for SUVs and trucks from 2014−2021 as oil prices stuck lower. Peak oil demand isn’t here, but it’s coming.

Lukoil VP Leonid Fedun exposed the fragility of Russia’s ‘oil power’ in an op-ed he recently penned for RBK arguing to cut output by 20−30% to prop up prices and serve the national interest. Fedun was effectively admitting that the oil sector cannot sustain production and investment with the size of the discounts exports currently receive and without imports, proffering the idea to save face from reality as it sets in. Russian firms will likely never again meet marginal demand increases with greater production. Nor can the economy truly afford to throttle production at those levels without significant damage to countless people’s livelihoods. Russia played second fiddle as a prime mover on oil markets for seventy years. Now as Europe opts to look to the Middle East and across the Atlantic instead, it’s signed Russia’s death warrant as an oil power.

Nick Trickett is commodity analyst at Fitch Solutions. He studied at the London School of Economy and the European University in St. Petersburg.

This article is originally published by