In the beginning of the war the economic sanctions against Russia didn't have the huge impact, that was foreseen in the West. But after the setbacks in Ukraine and mobilization in Russia, the real economy fell in a recession. The economic crisis will deepen in 2023, expects Boris Grozovski. The state of the Russian economy at a glance.

Elvira Nabiullina, head of Russia's Central Bank (picture Kremlin)

Elvira Nabiullina, head of Russia's Central Bank (picture Kremlin)

by Boris Grozovski

The September-October enlistment drive has done to the Russian economy what the West’s sanctions have so far failed to do. The real estate market, demand for credit, and consumer sentiment all show a noticeable decline. Absent oil and gas revenues, the federal budget would be in deep deficit. Russia’s brainwashed citizens are starting to suspect that the war is eating away at their well-being. The recession will continue in 2023.

In the fall of 2022, the Russian army, effectively defeated in Ukraine over the spring and summer, needed a serious influx of soldiers. According to the official count, 318,000 men were drafted, or nearly 1 percent of those liable for military service—and that figure is likely an underestimate. Even more people, up to 1.5−2 times as many and predominantly men, have left the country to escape the draft. Many have lost their incomes and have had to reconsider their investments and consumption patterns.

Yet the Russian economy has proved quite resilient to war and sanctions. In April and May most forecasters expected Russia’s GDP in 2022 to fall by 7–8 percent, while some predicted a 12–15 percent fall. Investments were expected to go down by 25–28 percent and retail trade by 8–9 percent, while prices were expected to rise by 20−25 percent. Russia's GDP grew 4.7 percent in 2021, and this was another argument for a sharp recession owing to a high base effect.

However, things turned out differently. The sharp decline in imports, bans on foreign currency exports, and a requirement for exporters to sell foreign currency earnings led to a sharp appreciation of the ruble, while state aid to banks and companies enabled them to keep up investment levels. Sanctions against Russian exports, extremely important in the medium and long term, proved ineffective in the short term because high energy prices continued to fill the state’s coffers.

According to the most balanced forecasts, the GDP decline in 2022 will be only 3.3–3.4 percent, inflation will level off at about 12 percent, investment will fall by about 1 percent, and the population’s real income will decline by 2–2.5 percent. Only the estimated decline in retail trade is close to the spring forecasts: 6 percent.

Industry in 2022 avoided a recession with the rapid growth in arms manufacturing. Since the beginning of 2021, according to an estimate by an economic think tank close to the Russian government, the share of weapons of undisclosed value in Russia’s industrial output has increased. Previously rarely exceeding 1–2 percent of all industrial production, the output of military goods has increased in 2022 to 4–5 percent of all production. In wartime, the army needs more tanks, missiles, and shells. Military production helps the GDP but has only a negative impact on the population’s economic well-being.

How technocrats avoided total collapse

In the first weeks of the war, experts forecasted a steep decline of the Russian economy. But after half a year the impact of Wester sanctions turned out to be less destructive as foreseen. The leadership of the Central Bank, the Sberbank and other main financial institutions were able to control the downfall of the Russian economy. Partly because of the policy of President Putin, who decided to neglect the pressure of the siloviki to nationalize as much as possible and gave the financial technocrats a free hand, total collapse was avoided.

In July, independent news-agency Meduza published a reconstruction about the role of Elvira Nabiullina, chairman of the Central Bank. In December, the Financial Times reported how Putin’s technocrats saved the economy to fight a war they opposed.

Still, Russian industry as a whole will finish 2022 without a recession. Construction and investment will also continue to grow. At the same time, private investments are gradually being replaced by state investments and peaceful investments by military ones.

Commodities, Real Estate, and Advertising

Owing to the uncertainties of wartime, private companies are reducing their investment programs. For example, Chernogolovka, a producer of soft drinks, froze its investment in new production facilities for 5 billion rubles, and Severstal refused to buy a new gas turbine. The City of St. Petersburg reduced from 55 billion to 30 billion rubles its planned investments in new subway construction in 2023. Budgetary support for investment in 2023 will decrease by 10 percent from planned levels, but priority programs, including spending on military equipment, will not be affected.

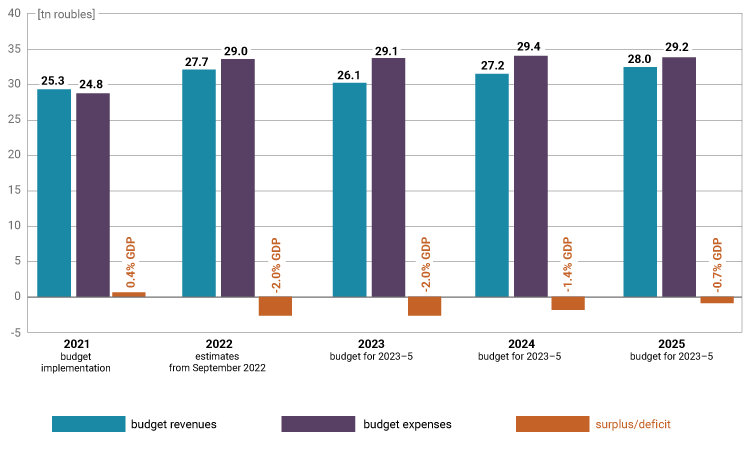

Forecast federal budget. Graphic OSW.

Already since March 2022 the auto market has experienced the hardest landing. Leading car manufacturers have left Russia, while Western suppliers of spare parts have been mostly banned or are observing the sanctions. Auto sales will shrink by about 60 percent this year, with only Chinese- and Russian-produced cars available. Restrictions on imports of electronics and the ongoing chip crisis further narrow opportunities for automakers. The supply of components through third countries is a narrow stream as Turkey and other countries try to avoid running afoul of US and EU sanctions. Deliveries through Central Asian countries are irregular because these routes are busy and clogged with other goods in transport.

Contrary to the expectations of Russian officials, Chinese automobile manufacturers are not in a hurry to open assembly factories in Russia, and the Chinese government is buying out foreign shareholders' ownership in such projects. The new production facilities will be developed on Chinese platforms.

The advertising market is in dire straits. According to most advertising agencies, advertising will fall this year by at least half. The activity of small and medium-sized businesses, especially in trade and services, is visibly decreasing. Small businesses are actively cutting staff and investment.

After the mobilization was announced, the demand for new real estate in Moscow fell sharply, by 36–37 percent. Most developers have to offer discounts of 5−30 percent to keep up sales. And apparently this is just the beginning: in 2020–21 prices rose sharply because of the state’s mortgage subsidies. The supply of new construction in the market has reached a five-year high, and buyers are leaving the market. A prolonged recession will lead to financial problems for developers, and the state is unlikely to continue to support mortgages: the budget is facing increasing difficulties, and the proportion of people with bad loans is growing.

Banking

In the spring of 2022 the Russian Central Bank imposed a sharp increase in interest rates to stop inflation and keep the ruble from falling. This led to a reduction in mortgage lending (by 21 percent in amount and 36 percent in the number of loans). For the sake of preserving lending, banks had to sharply increase the proportion of mortgages for which the borrower could offer only a small (10–20 percent) down payment.

The economic downturn and mobilization fueled an increase in bad loans. For example, in September 2022, nonpayment on car loans increased by 19 percent over a month; 13 percent of such loans are now overdue. Mortgage arrears rose even more significantly, by 35 percent, during September. Increased uncertainty, lower incomes, the forced departure of wage earners abroad, and mobilization have made it difficult for citizens to service loans.

Against the backdrop of mobilization, banks have reduced issuance of loans in all segments of lending, which also contributes to an increase in the share of overdue loans. Mortgage refusals have risen particularly sharply: banks fear that borrowers will be sent to war and will not be able to service loans. The tightening of banks' policies for the first time since 2015 has led to a decrease in the total debt of the population to banks. However, the quality of loan portfolios is tangibly declining as mobilization and the economic downturn make previously issued loans problematic. The possible winding down of concessional mortgage programs will make a decline in housing prices inevitable.

In turn, borrowers are also becoming more cautious. Now they do not view their economic prospects as bright, and since July they have been reducing the average mortgage by about 6 percent (at VTB, in the more expensive housing segment, by almost a quarter). So far, starting in 2015, mortgage subsidies have accelerated home prices, and the average mortgage has risen 2.7 times since then.

Restaurants, Education, and Leisure

Mobilization has also hit restaurants (their revenue has been halved), cinemas, jewelry brands, auto services, goods for construction and repair, bookstores, furniture makers, and fitness clubs, all of which are losing male customers. In large cities, many dance schools and gymnasiums have lost their male teachers: they fled the mobilization. Many of them now teach classes in Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Georgia.

In addition to declining demand for their products, many businesses are experiencing a shortage of experienced staff, who have been drafted into the army. The severity of the problem is evidenced by the fact that in October, the Ministry of Defense promised to mobilize no more than 30 percent of the employees of a single company. The vast majority of companies cannot protect their employees from the draft. For companies that cannot use remote labor and must invest time and resources in training qualified employees, this is a big problem. The new mobilization waves coming up in 2023 will be even more painful.

IT and exports

IT engineers have been the most mobile part of Russia’s labor force: more than 30 percent of IT specialists have left the country in 2022. Some have been helped by their employers to relocate to countries on Russia’s borders. The law obliges companies whose employees have received military notice at their place of work to deliver them to the employees. But there are cases of employers transferring employees for whom they received subpoenas or have placed them on leave, while in fact such people continue to work while hiding from mobilization.

Another indicator of the overall economic downturn is the decline in non-oil and gas budget revenues. In October 2022 they were 20 percent lower than a year earlier. The decline in revenues is forcing the government to raise taxes, cut non-war spending, and resort to debt. In addition to sectors of the economy that work for the domestic market, the iron and steel industry may be in a very difficult situation. Exports are plummeting, and the companies are forced to export their metal at steep discounts.

The population has begun to suspect that Putin’s military adventure is taking place at their expense. Although Russians’ real incomes are said to remain at 2021 levels, this may not be statistically true: Rosstat underestimates inflation and has once again changed its method for estimating the population’s income. Meanwhile, according to the Consumer Sentiment Index of the Russian Central Bank, the population's assessment of its current situation and its economic expectations have deteriorated sharply in the fall.

Expectations have been unjustifiably high since the beginning of the war: the first military victories, as in the case of the annexation of Crimea in 2014, caused an upswell of euphoric sentiment among the Russian people. That elation underwrote both increased support for the government and consumer optimism. In the summer, consumer expectations fell as the war effort dragged on. Ordinary Russians’ assessment of their current economic situation is declining, but currently it is higher than in the spring. The public sees the economic situation much more realistically now than it did in the spring of 2022. The awakening to war realities is slow and far from over, and growing economic disappointment will continue to strengthen negative attitudes toward Putin's dictatorship and the war.

About the author

Boris Grozovski is a prominent Russian journalist writing about the country's economy and development. His work has appeared in Forbes Russia, InLiberty, the Moscow Times, the New Times, Vedomosti Daily, OpenRussia and others. In 2002-2008 and 2014-2015 held various editorial positions at Vedomosti Daily (correspondent, economics editor, opinion page editor). Since 2011 Boris Grozovsky has been involved in various education and public speaking projects. He organized public lectures and discussions, summer and winter schools for the Gaidar Foundation and the Sakharov Center. Grozovsky also worked with the German Naumann Foundation, the InLiberty opinion platform, and the Moscow School of Civic Education.

This article was originally published by the Wilson Center (USA) here.