For the Netherlands, the risk of hybrid warfare is immensely greater than any form of conventional conflict. Countering hybrid Russian threats should therefore be a priority for the Dutch government, argues Guus Rotink. Rotink is one of the winners of the Raam op Rusland Pitch Competition for students. In his article, he explains why and how the Netherlands should lead the fight against Russian hybrid warfare, concluding his analysis with seven policy recommendations.

The car used by Russian hackers during their attempted attack of the OPCW in 2018 on display in the National Military Museum (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Ever since the Russian Federation took the world by shock with its swift annexation of Crimea in March of 2014, analysts, academics and policymakers have increasingly used the term “hybrid warfare” as an analytical construct in an attempt to explain Russia’s actions. Even though Russia certainly did make use of hybrid methods before March 2014 to gain influence over European states, the use of such methods has since become systematic policy, in which creating maskirovka plays a central role.

Today, aggressor Russia is engaged in a tenacious war with Ukraine and the debate on the future of European, and thus Dutch defence strategy and expenditure is gaining momentum. The recently promised delivery of Dutch F-16s to Ukraine and the focus on supplying conventional weapons on the highest international level such as within the Ramstein contact group have moved the issue of Russian hybrid warfare to the background. This article argues that the issue of countering Russian hybrid warfare, especially for the Netherlands, should be considered crucial and deserves a more prominent position in current debate on defence. It also discusses how this issue can be addressed.

What is hybrid warfare?

Hybrid warfare may be defined as a conflict that involves a number of conventional and unconventional forces, that can include both state and non-state actors, which share the same political purpose4. Since its definition is remarkably broad, the term has been criticized for not being analytically useful. Some say interstate competition is natural, and calling non-military means ‘warfare’ is therefore misleading. The definition is directly deduced from observing the enemy’s actions and thus subject to change. It is also not a new term; we can find examples of hybrid warfare throughout history, from Sun Tzu to the Peloponnesian War and from Napoleon’s Grand Armée to the German Wehrmacht.

Despite the criticism, the topic does provide a useful platform for discussion on the future of warfare and should thus be of interest to the Western powers, for which generating an effective response to security and defence challenges has rarely been an easy task.

Roughly, Russian hybrid warfare may be subdivided into five categories: information warfare, cyber warfare, proxy warfare, economic warfare and finally a mixture of covert and clandestine operations as well as traditional diplomacy. These various forms of hybrid warfare do not operate on their own, they coincide and are often symbiotic.

Why is hybrid warfare crucial for the Netherlands?

The ongoing war in Ukraine has rightfully shifted the focus of European analysts and policymakers to conventional means of warfare and to the ability to mount a sufficient defence with conventional forces in case of further Russian aggression. For example, in the fall of 2022, the Dutch government announced extra investments in its conventional defence, with the Netherlands reaching the NATO threshold of 2% GDP in 2024. Although these efforts are entirely justifiable, several reasons make it of utmost importance to not relinquish the efforts to bolster our defences from hybrid incursions.

Setting false narratives and installing doubt is often enough for the Kremlin to be able to polarize societies

First, the Netherlands is a country that is and has been particularly vulnerable to Russian hybrid warfare operations. The investigation into the downing of Flight MH17 and the referendum on the EU’s association agreement with Ukraine are two prime examples of events in which Russia attempted to create and exploit divisions by means of information warfare. Setting false narratives and installing doubt is often enough for the Kremlin to be able to polarize societies.

When we analyse Russian hybrid warfare, and in particular information warfare, we see a recurring problem of distinguishing people that genuinely want to voice their opinion and those that are trolls, sponsored by Moscow. In a democratic society where freedom of expression is prevalent, anyone can spread narratives, provoke demographic groups or frame governments and institutions. Whereas this freedom is clearly a positive attribute, it remains important to be aware of the fact that the transparency of our societies is often exploited by actors with malicious intentions.

In terms of Russian economic warfare, the Kremlin held significant leverage over the Netherlands and other Western European states prior to the war in Ukraine because of the large amounts of gas it exported to these states. This leverage was used by Russia to frame states such as the Netherlands as hypocritical: even though they repeatedly judge Russia for its lack of respect for human rights and international law, they kept funding the Russian state through energy purchases. The Kremlin exploited this aspect in its narrative labelling the Netherlands as insincere. Due to effective measures taken by the Dutch government as well as strong solidarity within the European Union, this energy dependency has now largely been revoked and the threat of Russian coercion through energy means has disseminated.

'The Netherlands is in a cyber war with Russia'

Unfortunately, this cannot be said for the threats in the sphere of cyber warfare. Despite continued government efforts to bolster cyber defence, Russia has previously succeeded to hack into Dutch sensitive information, such as during the hack of the Dutch police force in 2017, which, at the time, was investigating the MH17 downing. Furthermore, the 2018 attempted Russian hacking of the OPCW in The Hague was arguably a cyber warfare effort to gain an advantage in an information warfare operation. If Russian cyber hackers would have successfully impeded the OPCW’s investigations on the poisoning of Sergej Skripal and the Douma chemical attack, this would have strengthened Russia’s attempt of denying any involvement in both cases by means of an information operation.

Russian disinformation concerning the MH17 investigation (Photo: stopfakenews.org)

Russian disinformation concerning the MH17 investigation (Photo: stopfakenews.org)

The Russian agents that were involved in the hack were later expelled from the Netherlands, after which Minister of Defence Ank Bijleveld declared that 'The Netherlands is in a cyber war with Russia'1 and argued that the Dutch should get rid of naivety on this front. The Netherlands has produced valiant efforts to improve cyber defence, most notably in its strategy document Dutch Cybersecurity Strategy 2022-2028. The debate on these efforts should not regress, as the Dutch are likely to remain a target of Russian hackers due to the plethora of international organizations the nation plays host to.

Perhaps most importantly of all, a key element of the Russian hybrid strategy is that it is a tenacious one, often aimed at achieving results in the long term. This is because the Kremlin has viewed itself as fighting an ongoing war with the West since long before its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. For Russia, the traditional binary distinctions between peace and war no longer exist in the 21st century2. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Western response to Russia has been similarly persistent. However, the democratic nature of the West also entails that this persistence cannot be taken for granted and may change or attenuate, whereas a change in the Russian attitude towards the West would arguably require a much more unlikely and revolutionary change.

The Netherlands as a frontrunner

As concluded above, it should be deemed highly likely that Russia will continue to launch hybrid operations against the Netherlands and other Western states. In this, the Netherlands does not stand alone. In fact, European states face very similar threats. Baltic States such as Estonia are only a stone's throw away from Russia compared to the geographical distance between The Hague and the Kremlin but are faced with similar hybrid incursions. In this, information warfare is clearly the Kremlin’s most appealing instrument, because of its positive cost-reward balance as well as low risk.

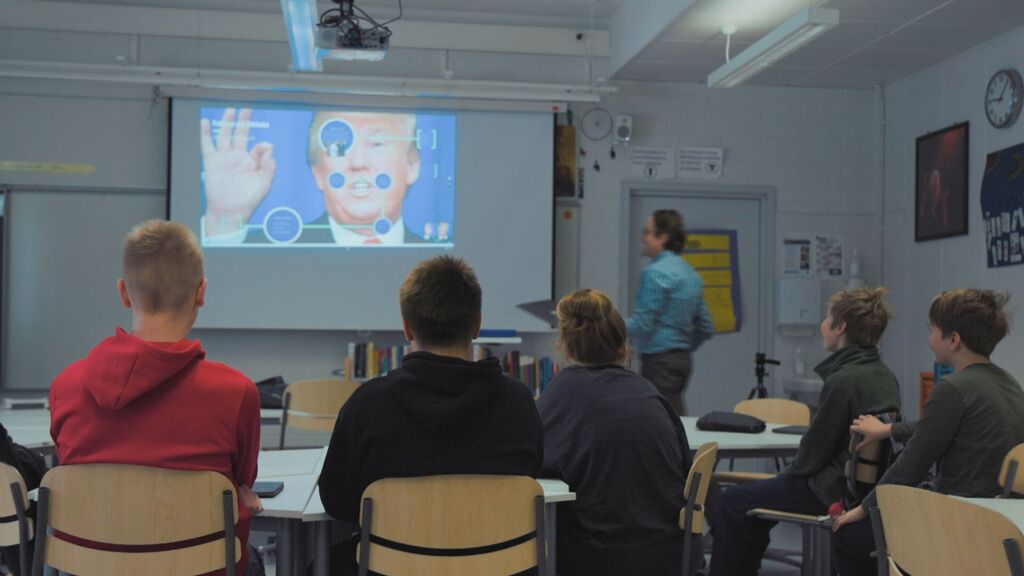

Finnish children are taught about fake news from kindergarten onwards. The country ranked first in the 2023 European Media Literacy Index. (Photo: YouTube)

Finnish children are taught about fake news from kindergarten onwards. The country ranked first in the 2023 European Media Literacy Index. (Photo: YouTube)

Members of international organisations such as the EU and NATO are often targeted by Russia as part of that organisation instead of as an individual state. The Kremlin understands that its information campaigns are more effective when they target the international organisations that states are part of rather than the state individually. This is because states like the Netherlands are heavily embedded in these organisations. Russia is likely to make attempts at discrediting a state’s membership of these organisations and instilling an idea into a state’s population that a state’s membership of such organisations is unbeneficial or even harmful.

It is clear that European states share this common problem of Russian hybrid warfare which is unlikely to dissolve naturally. Thus, we should propose and promote solidarity and cooperation, as is good European practice, on the issue. The Netherlands ought to be a frontrunner in this regard; Dutch foreign policy has had the promotion of democracy and international law at its core for decades. Where better to propagate these ideals than on home soil, forming a front against hybrid threats in order to defend Western democracies more effectively?

In order to improve and ensure continued resilience against Russian hybrid strategies the following is recommended:

- Informing the population. More effective policies to inform the public of information wars are essential to counter the problem at hand. Critical thinking is an important asset that should be taught from an early age, and the public should be made aware that foreign powers such as Russia intend to sway the public’s opinion in its favour whilst making use of fabricated facts and narratives.

- Consulting with big tech. Many of today’s information wars are essentially fought on big tech platforms such as Twitter (currently rebranding to X), Facebook and Telegram. These spaces are often sanctuaries for those that spread false narratives or false information. More needs to be done to either remove or raise awareness of content intended to drive wedges in societies.

- Focus on transparency. Instilling a seed of doubt, making the population second guess the workings and aims of its institutions is often enough for the Kremlin to drive wedges in our societies. Therefore, decision-making processes, (criminal) investigations and elections amongst others must be inherently transparent, to remove the opportunity of creating smoke screens that aim to polarize.

- Maintain a high-level judiciary system and law enforcement. Groups that feel disconnected from society are often more susceptible to Russian meddling. Minority groups or groups of people that have lost trust in government institutions are easily swayed by the alternative narratives posed by Moscow. Coinciding with transparency, this cynicism can only be taken away by a state-of-the-art judiciary system and law enforcement agencies which do everything to avoid discrimination of minority groups.

- Economic progress. Groups that are economically at a disadvantage compared to others in a state are also more likely to be prone to the Kremlin’s narratives. An excellent example of how economic progress trumps the Russian effort comes from Estonia, where polls show that the largely ethnic Russian population in the country’s eastern regions does not wish to be part of Russia because of its lesser economic situation. In fact, citizens of the Russian border town of Ivangorod attempted to join Estonia on multiple occasions for exactly those reasons3,5.

- Avoiding naivety & dependency on authoritarian regimes. Western European nations such as the Netherlands have continuously opted for a policy of appeasement towards Russia, retaining economic relations. Whereas a reinstation of such a relationship in a post-war era should not necessarily be avoided, a change in our posture towards such a relationship is important. States such as the Netherlands ought to improve their middle to long-term strategical thinking when dealing with authoritarian regimes to avoid situations such as the energy dependency discussed earlier in this article. Going forward, partnerships with authoritarian regimes over vital resources and industries require extensive strategic thinking. We already see positive developments on this front in cases such as exports of semiconductor chips.

- International cooperation. Allies, especially Eastern European states that were formerly part of the Soviet Union, have greater experience in dealing with Russian threats and are often better aware of what is required to counter the Kremlin’s influence. In this regard, there are positive developments worth mentioning, such as the opening of the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats in Helsinki in 2017 or the renewed focus of the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) on the hybrid domain. It is important for the Netherlands to participate actively in these organisations, where it can learn lessons on areas such as cyber warfare from Estonia, a state that has a highly digitalized society and already cooperates extensively with international partners on the issue, for example by opening a back-up of all its digital data in Luxembourg in 2019.

To the Dutch, the risk of Russian hybrid warfare is immensely greater than any form of conventional conflict

It is understandable that in the midst of an ongoing war in Ukraine, the production of tanks and ammunition stands higher on the agenda than countering hybrid threats. And as much as we need to ensure our continued support for Ukraine in its struggle, the Netherlands needs to realize that to the Dutch the risk of Russian hybrid warfare is immensely greater than any form of conventional conflict. Much has already been done on this issue, but it is vital to keep it in the spotlight and on the agenda in the years to come.

Prior to the outbreak of all-out hostilities in Ukraine in February 2022 the Dutch posture towards Russia often seemed lethargic and naïve. That has now of course changed but the current attitude is not to be taken for granted. Governments change, policies get altered, such is the fate of a democracy. What we need to do is instil the idea into the population as well as policymakers that even though we are prosperous and enjoy great freedoms, we are vulnerable to information operations, hacking attempts and economic blackmail.

One thing is almost certain: unless we see an alteration in the Kremlin of November Revolution proportion, the Russian effort will be persistent, as Russia views itself at war with the West and has opted for a cost-benefit strategy that involves all elements of its state, from propaganda to diplomacy. It already did so prior to its invasion of Ukraine, the only change being the all-out deployment of conventional forces. In the new world order that follows, the Netherlands can and must take the lead in repelling the hybrid threat, be it from Russia or other authoritarian powers that wish to expand their influence.

Annotations

1. AD. (2018, October 14). Bijleveld: Nederland in cyberoorlog met Russen. https://www.ad.nl/buitenland/bijleveld-nederland-in-cyberoorlog-met-russen~ac0b5320/

2. Chivvis, C. S. (2017). Understanding Russian “Hybrid Warfare” And What Can Be Done About It. In RAND Corporation. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT468.html

3. Lagnado, A. (1998, July 31). The Moscow Times. The Moscow Times. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/1998/07/31/town-petitions-to-join-estonia-a287105

4. Murray, W., & Mansoor, P. R. (2012). Hybrid Warfare: Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present. Cambridge University Press.

5. Radio Free Europe. (2010, April 13). Russian Border Town Seeks To Join Estonia. RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/Russian_Border_Town_Seeks_To_Join_Estonia/2011276.html