In Putin’s Russia, the space for honest literature has shrunk dramatically. Publishers self-censor, books are being pulled from stores, and writers risk prosecution for even hinting at forbidden subjects. This has revived a Soviet-era practice once used to outmaneuver censorship: tamizdat, an international ecosystem of publishers offering Russian writers the freedom they no longer have at home. Svetlana Satchkova explains how it works.

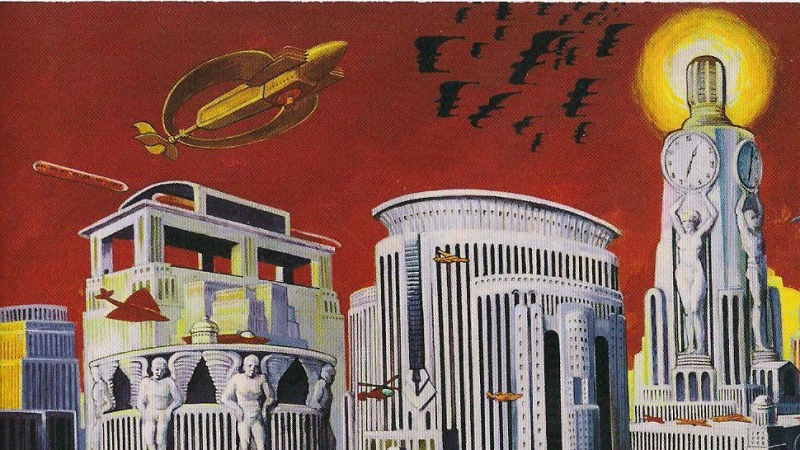

Cover of Yevgeny Zanyatin's novel 'We', generally considered the first case of 'tamizdat' (1924)

Cover of Yevgeny Zanyatin's novel 'We', generally considered the first case of 'tamizdat' (1924)

Before February 2022, Putin’s government paid almost no attention to literature. If writers were targeted, it was usually for their outspoken opposition to the regime, not for their books. But after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the pressure started to tighten, with new censorship laws appearing one after another. The first notable piece of legislation, which has become informally known as the 'fake news about the war' law, was passed in March 2022. Its goal was to prosecute anyone who contradicts the state’s official line about Putin’s military campaign or even calls it a 'war' rather than a 'special military operation'.

Another turning point came in the summer of 2022, when State Duma deputies attacked the popularity of Summer in a Pioneer Tie by Elena Malisova and Katerina Silvanova—a bestselling young adult novel about two same-sex teenagers in a Soviet Young Pioneer camp discovering their attraction to each other. To the officials, the book’s success showed that 'family values' were being eroded. The book began disappearing from stores, and not long after, an updated 'LGBT-propaganda' law was passed, banning this kind of content. In 2023, the 'world LGBT movement' was labeled an extremist organization, and publishing any queer-themed material became a criminal offense.

Soon after, afraid of provoking the authorities, publishers began redacting not only hints of queer relationships but also any references to the war or parallels with the current political situation. Sometimes it was just a sentence; other times entire pages vanished or were visibly blacked out. And it wasn’t only themes that became off-limits. Certain authors were effectively banned as well: the works of writers labeled 'foreign agents' or 'extremists' for their anti-war stance, such as Boris Akunin, were pulled from sale. When, in May 2025, some booksellers in various Russian cities were fined and several publishers arrested, it became clear that a new era in the Russian book industry had begun. And with it, Soviet-era publishing practices that seemed to have ended with the collapse of the USSR came back to life.

Samizdat and tamizdat

Two Russian words that have become known worldwide alongside gulag, apparatchik, and others are samizdat and tamizdat. The former refers to crudely produced, hand-made books, or even simple stacks of barely legible handwritten pages, that circulated because publishing certain literature through official channels in the Soviet Union was impossible. It is believed that this particular way of dealing with state censorship had its start sometime in the 1930s, but received its name in the mid-40s after poet Nikolay Glazkov began signing his typewritten collections 'sam sebya izdat' ('published by myself'). Texts were copied by the author or readers without approval from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, usually by typewriter, camera, or by hand. People got creative, building homemade typewriters and printing devices from stolen, found, or improvised parts. As technology improved, early photocopiers, tape recorders, and later, during perestroika, even computers were used.

These practices were incredibly risky. Paper, especially carbon paper, was hard to obtain, not only because of shortages but because anything connected to printing was tightly monitored. Since Stalin’s era, every typewriter and every piece of printing equipment had to be registered. Factories sent the KGB, the secret service of the Soviet Union, a sample page showing that machine’s unique print fingerprint, and later, when personal typewriters went on sale, stores sent the KGB these samples together with the buyer’s name. This system allowed the state to trace any copy back to a specific device and its owner.

Police and the KGB frequently raided the homes of people they suspected, often acting on neighbors’ denunciations. Even owning carbon paper could lead to arrest. Producing or possessing samizdat was treated as anti-Soviet agitation, a criminal offense under several articles of the Criminal Code. Punishments ranged from prison terms to forced psychiatric confinement, internal exile, and labor-camp sentences. Because of that, samizdat was shared only with people you trusted, usually overnight, so the material didn’t stay in one person’s hands for long.

Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita circulated widely in samizdat after Soviet censors blocked its publication

Not all samizdat was political. Some Silver Age [period around the turn of the 19th to 20th century, ed.] poets like Konstantin Balmont or Vyacheslav Ivanov were unpublishable because their work was considered alien to the proletarian state, their style too irrational or decadent. Works about yoga or karate were restricted since they promoted foreign spirituality, self-discipline outside state control, and small autonomous communities. Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita circulated widely in samizdat after Soviet censors blocked its publication; its religious and philosophical themes and its criticism of authority clashed with official ideology. In 1966–67 – more than 25 years after Bulgakov’s death – it appeared in the magazine Moskva in a heavily edited form, which sparked another wave of samizdat copies based on the full text.

The revival of tamizdat since the war

But samizdat in its original Soviet sense hasn’t survived. Today there’s no need to produce books by hand or with improvised printing devices, because nearly everything is available online or can be shared as a digital file. The term samizdat still exists, but its meaning has changed completely. It has essentially become a synonym for self-publishing, whether in print or digital form, and now refers to writers whose work was not taken on by traditional publishers for commercial or editorial reasons. Younger readers unfamiliar with Soviet history might not even know the term’s earlier meaning.

But its sibling practice, tamizdat ('published there'), has become a remarkably active field over the past four years. The term refers to books in Russian that appear abroad, usually works that cannot be published in Russia due to censorship. In Soviet times, manuscripts were smuggled out of the USSR and printed by small foreign presses, sometimes even without the author’s knowledge. The first work generally considered tamizdat is Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We, published in the United States in 1924, a book that inspired Orwell’s 1984. After its appearance, Zamyatin faced a campaign of persecution: the planned Soviet edition of his collected works was halted, his plays were banned, and he was forced out of the Writers’ Union. In 1931 he received permission to emigrate and left the USSR.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the need to publish abroad effectively disappeared. In the new democratic Russia almost anything could go into print, and readers who had been missing out on certain books for decades finally got the chance to read them. But that openness has vanished in the current climate. Following the invasion of Ukraine, tamizdat has returned and a network of small publishers devoted to this literature has sprung up across Europe and the United States.

Bulgakov's novel 'Master and Margarita' is one of the most famous examples of 'samizdat' in the Soviet Union

Bulgakov's novel 'Master and Margarita' is one of the most famous examples of 'samizdat' in the Soviet Union

More than thirty Russian-language publishers currently operate abroad, according to Yakov Klotz, a scholar of tamizdat and founder of the New York–based Tamizdat Project, a philanthropic organization that also publishes books censored in authors’ home countries. Among those publishers is Meduza, the independent Russian-language outlet based in Latvia, which has launched its own imprint focused mainly on journalism and political nonfiction while also publishing fiction. Vidim Books, founded by Poland-based Alexander Gavrilov, works with authors who have been designated 'foreign agents' or are no longer allowed to publish in Russia. Writer Boris Akunin has also created his own press, BAbook, which releases his own titles as well as works by other persecuted writers.

The largest of them in terms of output is Freedom Letters, founded by Georgy Urushadze, the former head of Russia’s Big Book award, who left the country after it invaded Ukraine. About half, if not more, of all Russian-language books published abroad are theirs. In the two and a half years since its founding, Freedom Letters has released 250 books in print, electronic, and audio formats. They publish in many countries and in several languages: Russian, Ukrainian, and English. Their first book in Belarusian is due out in December.

'We plan to publish even more books, and we are also starting a large program of translations from English, German, French, Bulgarian, and Polish into Russian,' Urushadze says. 'Freedom Letters books are sold in Russia, and we even print them there, demonstrating the weakness of Putin’s regime. Last year, we printed queer books and titles sharply critical of the regime just a mile from the Kremlin. Naturally, the authorities are trying to punish us. Many of our authors and I myself have been labeled “foreign agents.” I have already been tried in Russia. They have issued a travel ban in case I ever get the idea to go there. They file lawsuits against the publishing house. Our authors are declared “extremists” and “terrorists” for supporting Ukraine. The Prosecutor General has banned many of our books. Roskomnadzor [the Russian government’s internet watchdog, ed.] has blocked our website in Russia. And finally, several thousand copies of Sergey Davydov’s Springfield and Ivan Philippov’s Mouse were destroyed.'

Literary ecosystem in exile

Around these publishers, a whole ecosystem has begun to form. New Russian-language bookstores have opened across mainland Europe, as well as in London and Israel. New literary prizes focused on tamizdat writing have appeared, along with dedicated book fairs and public events. Recently, the Berlin-based shop Babel Books launched Tutizdat, an online bookstore that brings together all Russian books issued by presses outside Russia and serves as a central platform for news about tamizdat publishers’ activities.

The channels for bringing tamizdat books into Russia are limited, although they do exist. Buying electronic versions in Russia is usually impossible because international bank cards are blocked. Some books can be found on Russian online marketplaces such as Ozon or Wildberries, but only if you know what you are searching for. According to Urushadze, Freedom Letters titles can sometimes be found in independent bookstores, although these are becoming fewer. For electronic versions, the press sells books inside Russia for rubles and cryptocurrency through a Telegram bot: letterspay_bot.

Publishing in Russia from abroad

For many Russian writers in exile, there is no real choice. If they want to publish, they rely on these small tamizdat presses. But some writers who live outside Russia continue publishing their books at home in Russia, mainly because they want to reach a wide Russophone audience. This comes with a price. They must ‘sanitize’ their books to avoid attracting the attention of censors. Two such writers I contacted declined to comment, saying they didn’t feel comfortable discussing the issue. Perhaps this is because they understand that publishing in Russia today may be ethically questionable.

I don’t intend to publish anything in Russia for the foreseeable future: I don’t want to support Putin’s war effort economically

I can explain my own views. My last book in Russian came out in 2020, well before the invasion. It’s still being sold in Russia in various formats, as far as I know, but I’m not receiving royalties. I’ve lost contact with my publisher, Eksmo, the largest in Russia. They haven’t sent me sales figures since early 2021. When my agent reached out a couple of years ago, the publisher ignored her. I will probably never know whether this is because I now live abroad, or because it’s simply their usual way of doing business. In any case, I don’t intend to publish anything in Russia for the foreseeable future. The most important reason is that I don’t want to support Putin’s war effort economically. Even if a publisher is run by like-minded people, they still pay taxes and participate in the Russian economy.

Others, however, make different choices. In an interview with Republic, Polina Barskova, who continues to publish in Russia, said that when she imagines her ideal readers, she thinks of specific people living there. For them, being able to walk into Poryadok Slov (an independent bookstore in Saint Petersburg) and buy her books matters. Much also depends on who wants to publish her. 'If some glossy Moscow magazine invited me, I would probably say no. But when Irina Kravtsova [editor at Ivan Limbakh press, SS] or Igor Bulatovsky [poet and translator, SS] invite me, I agree without hesitation.'

A friend of mine, who also publishes in Russia, likewise thinks of concrete people when making his decisions. 'I’ve been publishing with the same house for almost fifteen years,' he told me. 'The people who work there are dear to me, and I feel deeply loyal to them. It would be strange to boycott them now. On the contrary, I’m sure that as long as there are publishers that continue to exist in spite of what’s happening in Russia, it’s important to support them.'

Help ons om RAAM voort te zetten

Met uw giften kunnen wij auteurs betalen, onderzoek doen en kennisplatform RAAM verder uitbouwen tot hét centrum van expertise in Nederland over Rusland, Oekraïne en Belarus.