Do we witness a ‘reset’ in German-Russian relations? On Iran and Nord Stream 2 a rapprochement between Putin and Merkel is possible, writes security expert Hannes Adomeit. But on all other issues the disagreements are numerous and substantial.

Are we about to witness the beginning of a rapprochement and a ‘reset’ in German-Russian relations? One could be tempted to think so on the basis of a plethora of recent visits by top German officials to Russia.

President Putin welcomes chancellor Merkel in Sochi. May 2018. Picture Kremlin

On 10 May, foreign minister Heiko Maas flew to Moscow for talks with his Russian counterpart, the first in his new ministerial capacity after the formation of the coalition government of the conservatives (CDU/CSU) and social democrats (SPD). Officially, the talks concerned the overall state of German-Russian relations, the conflicts in Syria and eastern Ukraine, and the state of affairs after the United States’ abrogation of the 2015 P5+1 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran. On 14 May, economics and energy minister Peter Altmaier (CDU) flew to Kiev, the following day to Moscow and then back again to Kiev, mainly to discuss the controversial Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project and the consequences of actual and possible future US sanctions against Iran. On 18 May, finally, Chancellor Angela Merkel met with Russian president Vladimir Putin in Sochi for talks on all of the above subjects.

Thus, concluded the Berliner Zeitung, ‘after a long period of increasing tensions in the German-Russian relationship, things are moving in the direction of détente’.

Iran and Nord Stream 2: islands of cooperation

Interpretations of a possible improvement of the strained relationship between Berlin and Moscow have focused mainly on the convergence of EU, German and Russian approaches to maintaining the Iran nuclear agreement and construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. Correspondingly, Dirk Wiese (SPD), the German government’s coordinator of civil society policies towards Russia, Central Asia and the countries of the EU Eastern Partnership, has called Iran and Nord Stream 2 ‘islands of cooperation’ with Moscow.

Concerning Iran, German officials have not only supported their Russian counterparts regarding their adherence to the nuclear agreement but also to persuade them to use their influence in Tehran so that it, too, would continue to honour it. It is safe to assume that Moscow does not need such prompting. It has never been in the Kremlin’s interest to foster the transformation of Iran to a nuclear power. This is not only because of the likely negative repercussions on regional stability but also because of the fact that the proliferation of nuclear weapons devalues Russia’s special status as a nuclear power, no matter whether this concerns Iran, North Korea or any other country. Furthermore, Berlin and Moscow agree that, whereas the nuclear deal may have its flaws, as Merkel stated at the joint press conference with Putin, it was better ‘to have it than none at all’.

Merkel: better to have deal with Iran than non at all

The problem both Russia and Germany have with Trump’s withdrawal from the agreement are the American ‘secondary’ – ‘extraterritorial’ or ‘third party’ – sanctions.

According to guidelines issued by Washington’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), the agency responsible for administering most U.S. sanctions, the re-imposition of sanctions will occur in three phases. Initially, OFAC will revoke general and specific licenses related to Iran and replace them with licenses authorizing limited ‘wind-down’ activities. On August 6, in addition to certain primary sanctions, the United States will re-impose secondary sanctions with respect to Iran’s purchase of U.S. dollar banknotes; the provision of graphite and raw or semi-finished metals, including steel and aluminium; Iranian sovereign debt; and certain automotive sector activity. On November 4, OFAC’s general ‘wind- down’ licenses will expire and the agency will re-institute secondary sanctions regarding shipping; Iranian petroleum, petroleum products, and petrochemical products; crude oil exports; the Central Bank of Iran and other Iranian financial institutions; financial messaging services; and insurance services.

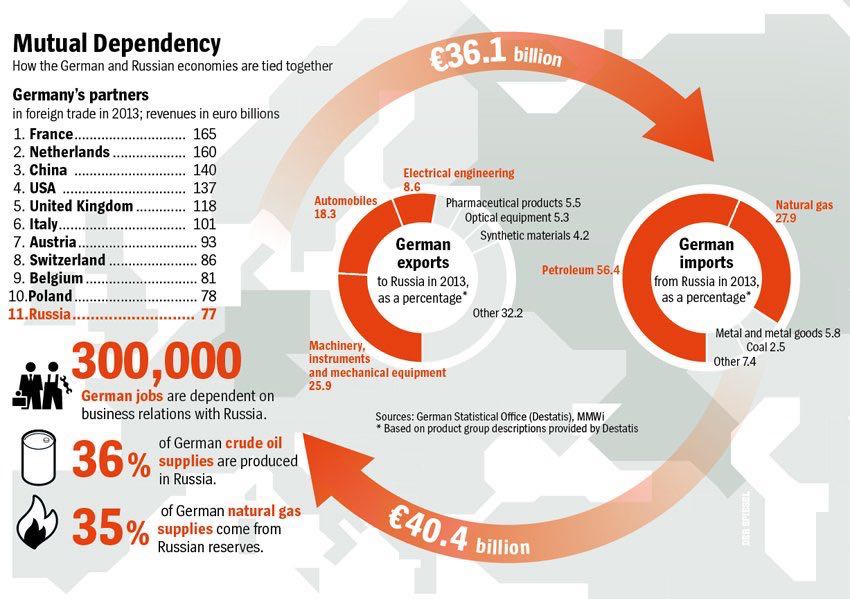

Trade balance between Germany and Russia, before Ukraine-crisis.

Measures to blunt impact sanctions

Russia and the EU are considering measures to blunt the impact of the sanctions. Included in those measures is the planned activation of the EU ‘blocking statue’, which would bar EU companies from complying with the extraterritorial effects of U.S. sanctions. It is also intended to insulate EU companies from certain U.S. sanctions penalties.

As for Russia, the Russian parliament introduced legislation that, too, would function like a blocking statute, imposing criminal liability for compliance with U.S. and other foreign sanctions against Russian parties. Whereas OFAC has sometimes worked with companies abroad when blocking legislation is in place, the agency has also enforced U.S. sanctions irrespective of another country’s blocking laws. As a result, Russian and German businesses, as well as those of other countries, including EU member states, are now faced with the unpalatable choice of deciding which country’s laws they are going to violate, those of their own or those of the United States.

The threat of US secondary sanctions faced by Russia, Germany and other EU countries is not only connected with Iran. It extends to Russian energy export pipelines, including the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline.

Until 11 April 2018 the German government’s stance was unbending. It consistently denied the highly political character of Nord Stream 2, asserting that it was simply a ‘commercial project’.

Existing and planned pipelines. Graphic Wikimedia

Ukraine involved

The major problem with Nord Stream 2, however, is connected with Russian policies toward Ukraine. If the pipeline were to be built and a new pipeline to Turkey replacing South Stream became operational, as Alexei Miller, CEO of the Russian energy giant Gazprom explained as early as December 2014, the role of Ukraine as a transit country would ‘be reduced to zero’. This would deprive Ukraine of revenue for the transit of Russian gas to Europe of $ 3 billion annually. In order to justify the deal, top German government officials have insisted on Ukraine remaining an important transit country for Russian gas. Merkel confirmed that position after talks with Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko in Berlin when she said that she had made it clear in a telephone conversation with Vladimir Putin the day before, ‘that, from our point of view, the project Nord Stream 2 is not possible without clarity as to how the Ukrainian transit role will continue’.

Merkel on Nord Stream 2: political factors have to be taken into account

That was not new. What was new and completely unexpected was her acknowledgment that ‘of course, political factors have to be taken into account’.

This, it stands to reason, is one of the major reasons why, apart from the economic benefits, Russia is averse to change its mind. Putting a positive spin on the mid-April talks, Altmaier discerned ‘positive responses’ by the Kremlin and that it was ‘prepared to make concessions’. Such views may have been prompted by Gazprom’s Miller who had announced his company's readiness to ensure transit supplies of Russian gas through Ukraine at the level of 10-15 billion cubic meters per year.

However, there was a vague condition attached. Ukraine had to ‘prove the economic feasibility of a new contract’. Given that small volume and the uncertainty as to how ‘economic feasibility’ was going to be determined, Miller’s promise can hardly be considered a meaningful concession. Such a verdict is warranted even more by Putin’s qualification conveyed to Merkel in Sochi that Russia could continue to send natural gas via Ukraine to the EU ‘as long as this is economically justified’.

But what volume of gas transit would be ‘economically justified’, and what specifically did Altmaier have in mind when he demanded that the transit gas flow through Ukraine had to be ‘substantial’? According to official data provided by Kiev, the capacity of the Ukrainian gas transportation system at the input is 288 billion cubic meters, at the output some 178.5 billion cubic meters, of which the countries of Europe could receive 142.5 billion cubic meters. In 2017, the volume of Russian natural sent via Ukraine to European customers rose by more than 9 percent to 93.5 billion cubic meters. One of the figures discussed unofficially in Berlin for a ‘substantial’ flow is 38.5 billion cubic meters, arrived at by subtracting the 55 billion cubic meters of Nord Stream 2 from the current Ukrainian transit volume. There are no indications, however, that the Russian side would agree to such a figure.

Nord Stream 2

The project envisages the construction of a 1,220-kilometer pipeline, with a total capacity of 55 billion cubic meters annually, to transport gas from Vyborg in Russia via the Baltic Sea to Greifswald, Germany. It will follow the route of Nord Stream completed in November 2011.

Five European energy companies – Germany’s Uniper SE (formerly E-ON) and BASF Wintershall, Royal Dutch Shell, France’s ENGIE and Austria’s OMV − have committed to provide long-term financing for 50 percent of the total cost of the project, which is currently estimated to be €9.5 billion. Each European company will fund up to €950 million but Gazprom is and will remain the sole shareholder of the project company, Nord Stream 2 AG.

In March 2018, from the technical point of view, the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency, the last German authority to approve the construction and operation of the pipeline, did so. Finland agreed in April. Russia’s consent is still lacking but is certain to come so that only permits by Denmark and Sweden are still outstanding.

Construction work began at the beginning of May 2018 and is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2019.

Nord Stream delayed

But even assuming German-Russian agreement on ‘substantial’ transit volumes, Nord Stream 2 could still be brought down or at least significantly delayed. This could be a consequence of U.S. opposition to the project. Washington’s ‘Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act’ law, adopted by overwhelming majorities in the Senate and the House of Representatives and signed by president Trump on 2 August 2017, gives the government discretionary authority to impose sanctions, including extraterritorial sanctions, for a person or entity that ‘makes an investment […] or sells, leases, or provides goods, services, technology or information to the Russian Federation for the construction of Russian energy export pipelines’. The threat is serious. Thus, U.S. deputy assistant secretary Sandra Oudkirk, an energy policy expert at the state department, said on a visit to Berlin on May 17 that the United States opposed Nord Stream 2 and could impose sanctions on it because of its potential to increase Russia's ‘malign influence’ in Europe. ‘We are exerting as much persuasive power as we possibly can’ to stop the project, she warned.

Trump’s abrogation of the nuclear agreement may have pushed Germany and Russia together on this issue. Germany (and other U.S. ‘allies’) now share Russia’s fate of being subject to sanctions. And the two governments are committed to the construction of Nord Stream 2. However, these two ‘islands of cooperation’ are surrounded by a sea of malign Russian behaviour.

Substantial disagreements

Merkel has never harboured any illusions about the development of the ‘Putin System’ away from democracy, a market economy with fair competition, a law-based state and an active civil society. To Putin’s visible irritation this became evident in her opening statement at the press conference in Sochi. In obvious allusion to the case of Heiko Seppelt, who had reported on doping scandals in Russia and was refused accreditation to the World Cup before the German foreign minister appealed to Moscow on his behalf, Merkel said that she had pointed out (to Putin) that ‘freedom of the press is of decisive importance’ and that she had asked (him) that ‘particular cases’ (presumably including that of Seppelt) ‘should be reconsidered’.

Foreign minister Heiko Maas (SPD). Picture FAZ

The Russia-friendly approach taken by Frank Walter Steinmeier (SPD) as foreign minister and Sigmar Gabriel (SPD), first as minister for economics and energy and then as foreign minister, has been superseded by the duo of Heiko Maas and Altmaier. Altmaier belongs to the same party as Merkel and is considered to be one of her most trusted advisors, and Maas has struck entirely new cords for an SPD minister. In an interview with Der Spiegel on 13 April, he said that ‘regrettably, Russia has been acting in an increasingly hostile manner’. He deplored that, for the first time since the end of the Second World War, ‘chemical weapons have been used in the middle of Europe’, obviously meaning by Russia in Salisbury; cyber-attacks appeared to have ‘become an important part of Russian foreign policy’; and in Syria, Russia ‘is blocking the UN Security Council’. Maas ruled out the possibility of a step-by-step dismantling of the sanctions against Russia if Moscow fulfilled some of its obligations on eastern Ukraine as outlined in the Minsk-2 agreement, thereby adhering to the EU position that requires ‘full implementation’ of the agreement.

Crimea

In all of these meetings, at least publicly, Crimea failed to be mentioned despite the fact that the issue came into the spotlight when Putin triumphantly opened the Kerch Strait Bridge linking the Russian mainland with the peninsula. The German government is still angry about the case of Siemens gas turbines illegally delivered to Crimea, a violation that − upon German initiative – had led to additional EU sanctions on the list of persons and entities responsible for ‘actions undermining Ukraine's territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence’. In Sochi, Putin reiterated that there was ‘no alternative’ to the Minsk peace agreement to which Merkel added that it was the ‘only basis on which we can work’. They also supported the idea of a UN peacekeeping force in the Donbass and that Russia, Germany, France and Ukraine should continue to work together in the so-called Normandy format. All of this, however, is rather meaningless since ‘full implementation’ of the Minsk agreement is not in sight. Not a single one of its provisions has ‘fully’ been carried out; there is disagreement on the mandate and modalities of a UN blue helmet mission; and the Normandy process can only work if there were to be a significant change in Moscow’s policy that still is aimed at using the Donbass as an instrument for preventing Kiev from pursuing the European option.

Gas turbine of Siemens. Picture Wikimedia

Divergence on Syria

German and Russian perceptions and policies in the Syrian conflict also diverge. They are far apart on Bashar al-Assad, who was received by Putin in Sochi just one day before the German chancellor’s arrival, and the role he should play in any peace settlement and the future shape of the Syrian domestic political system. Merkel has been incensed by the combined Russian and Syrian air campaigns and the large-scale destruction of Syrian cities, including Aleppo, and the huge civilian casualties the bombardments that have been a major contributory factor for the flow of refugees to Germany.

The two governments are at odds also over who is to pay for reconstruction. To add insult to injury, it seems that Moscow wants Berlin to repair the large-scale damages the Russian air force has inflicted on the country and assume a major role in the reconstruction and resettlement of Syrian refugees. Furthermore, whereas the Kremlin wants Germany to stop linking political demands to the extension of humanitarian aid, Merkel, as she stated in Sochi, wants Moscow to exert influence on Assad to rescind a decree that threatens to confiscate the property of refugees who fail to return to their homes in the next few weeks.

Maintaining Assad in power and eradicating any opposition to the regime in Damascus are goals that Moscow shares with Tehran. The Kremlin, therefore, is aiding and abetting the more far-reaching aims of the Mullahs with the help of their Revolutionary Guards and Lebanon-based Hezbollah militia in Syria to create a contiguous Shia-dominated area stretching from Tehran via Baghdad to Damascus and Beirut, as well as spreading their influence and control beyond that area. The German government, however, considers Iran’s role in the Middle East as destabilizing and also wants Teheran to curtail its missile programme. These, too, are positions that Moscow at least publicly fails to endorse.

Turkey

The German concern is heightened even further by the developments in Turkey and the country’s increasing cooperation with Russia, undercutting the international sanctions against Russia, helping through Turkish Stream to secure Gazprom’s Miller goal of terminating all Russian gas flows through Ukraine and supporting the Russian military-industrial complex by purchasing S-400 air-defence missiles.

Most significantly, the de facto cooperation in the quadrilateral Putin, Assad, Erdoğan and Khamenei is yet another painful reminder to German policy-makers that anti-democratic, repressive political systems have gained strength and spreading malign influence. It is also a confirmation that their concepts of Germany acting as a civil and civilian power in the framework of a liberal, rule-based order are inapplicable in the real world.

Former chancellor Schröder and Putin. 2008. Picture Kremlin

Germany will stay the course

To sum up, a substantial reordering of Russian-German relations is not about to occur. Contrary to what German apologists of Russian malign behaviour appear to believe, both ‘islands of cooperation’, Iran and Nord Stream 2, do not lend themselves to becoming starting points for a broad improvement of relations. The ‘islands’ remain isolated. The common position on the Iranian nuclear deal does not extend to Berlin condoning Teheran’s destabilizing activities in the Middle East. On that issue as well as on U.S. extraterritorial sanctions Merkel is careful not to turn parallel German and Russian interests into a coordinated anti-American policy. Similarly, Nord Stream 2 has remained controversial. It is not only a cooperative venture but also a bone of contention in German-Russian relations since it has been opposed by the United States, the Baltic States and Poland and Merkel now openly acknowledges these countries’ assessments that the project is not simply a commercial transaction but has serious economic and political implications.

What, then, explains the flurry of German-Russian talks last month and their interpretation as harbingers of a significant change in the relationship? For Putin it is important, to convey the notion, domestically and abroad, that vse normal’no, vse v poryadke, that everything is normal and in good order, and that the country is not isolated internationally.

For the German government the domestic exigencies are paramount. There is a growing groundswell of opinion in Germany that is tired of the government’s ‘confrontationist’ approach towards Moscow, warns of the dangers of war in Europe, calls for an end to economic sanctions against Russia and advocates renewed efforts at a ‘dialogue with Russia’. Such views are shared by influential sections in the SPD, as represented by Schröder, Steinmeier and Gabriel; parts of the Bavarian wing of the CDU, the CSU, with past and present leaders like Horst Seehofer, Helmut Stoiber, Ilse Aigner and Wilfried Scharnagl; prime ministers of the eastern Länder with economic interests in Russia; the populist and right-wing AfD; the left-wing Die Linke; the Eastern Committee of German industry (Ostausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft); and civil society organizations like the German-Russian Forum. Their representatives are incensed by the new foreign minister’s characterization of Russian foreign policy as ‘increasingly hostile’ and his blunt enumeration of Moscow’s malign activities.

The government, therefore, wants to be sure to be seen as heeding the demand for ‘dialogue with Russia’. For a genuine rapprochement and reset of relations, major changes of Russian domestic and foreign policy would be required.