The World Cup 2018 in Russia appeared to be flawless and therefore a success for president Putin. But to what extent did civil society participate in the organization of the tournament? In his master thesis Luuk Peters, student at Leiden University, sheds light on the expectations of society to have some say in the decision making process.

Zenit Stadium in St. Petersburg

Zenit Stadium in St. Petersburg

by Luuk Peters

In the midst of the FIFA World Cup in Russia, Vladimir Putin received FIFA president Gianni Infantino in the Kremlin. The mood was cheerful, as the organization of the tournament appeared to be flawless. In a press statement, Putin exploited the opportunity to tackle his fiercest critics by pointing at Russia’s hospitality. Putin’s use of the phrase 'our World Cup' seems to suggest that the tournament was a collective success. Indeed, the tournament had been propagated for and by the entire country. But to what extent did civil society participate in the organization of the tournament?

Civic engagement

Although civic culture in Russia is slowly but steadily developing, the overall level of regular participation in policy-making remains marginal. In a 2016 pollster by the Levada Center, 87% answered the question 'Can people like you influence government decisions in the country?' with 'probably not' or 'definitely not'. The same question regarding the region, city or neighborhood revealed a similar pattern. Moreover, 80% indicated that they were (probably) not ready to actively participate.

Can people like you influence government decisions in the country? (Levada, 2016)

|

Feb.06 |

Oct.07 |

Feb.10 |

Jan.12 |

Mar.13 |

Mar.14 |

Mar.15 |

Aug.16 |

|

|

Definitely yes |

2 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

To some degree yes |

13 |

21 |

12 |

15 |

10 |

11 |

15 |

11 |

|

Probably not |

39 |

31 |

34 |

28 |

35 |

38 |

38 |

38 |

|

Definitely not |

45 |

41 |

51 |

51 |

49 |

47 |

40 |

49 |

|

It is difficult to say |

2 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

Can people like you influence decisions in your region, city, neighborhood? (Levada, 2016)

|

Feb.06 |

Feb.10 |

Jan.12 |

Mar.13 |

Mar.14 |

Mar.15 |

Aug.16 |

|

|

Definitely yes |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

|

To some degree yes |

21 |

16 |

21 |

14 |

18 |

18 |

16 |

|

Probably not |

36 |

34 |

27 |

34 |

38 |

35 |

38 |

|

Definitely not |

39 |

46 |

47 |

46 |

41 |

39 |

43 |

|

It is difficult to say |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

Are you personally ready to play a more active role in politics? (Levada, 2016)

|

Feb.06 |

Feb.10 |

Jan.12 |

Mar.13 |

Mar.14 |

Mar.15 |

Aug.16 |

|

|

Definitely yes |

5 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

|

To some degree yes |

14 |

14 |

14 |

13 |

17 |

18 |

15 |

|

Probably not |

30 |

31 |

31 |

35 |

39 |

33 |

34 |

|

Definitely not |

47 |

46 |

47 |

45 |

36 |

38 |

46 |

|

It is difficult to say |

4 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

The Russian authorities verbally acknowledge the importance of including society in governance. However , it is often argued that the institutionalized instruments of public participation merely serve as seemingly democratic legitimizers of autocratically drafted policies. Many governance networks have been captured by the elite; civic organizations that the authorities consider to be loyal are allowed to participate, whereas opponents are excluded.

Saint Petersburg’s urban context

Saint Petersburg is a distinct city in Russia’s urban environment, with a more active society than elsewhere. The city’s spatial characteristics are among the main contributors to this. Under late socialism, groups aiming to distinguish themselves from the collectivity of socialism emerged. Saint Petersburg’s unique European aesthetics were key in the idea of having a distinct identity. These social groups would develop into the city’s first oppositional movements.

In the late 1990s, integration in the world economy became a pillar of Saint Petersburg’s development strategy. Occasionally, these ‘world city’ ambitions clashed with societal concern about preserving identity. In November 2006, the idea of constructing a skyscraper hosting Gazprom’s new headquarter in the inner city was announced. It sparked dissatisfaction as it would affect Saint Petersburg’s low-rise skyline, culminating in largescale public protests. Eventually, the skyscraper was relocated .

Zenit Arena: a chronology of concern

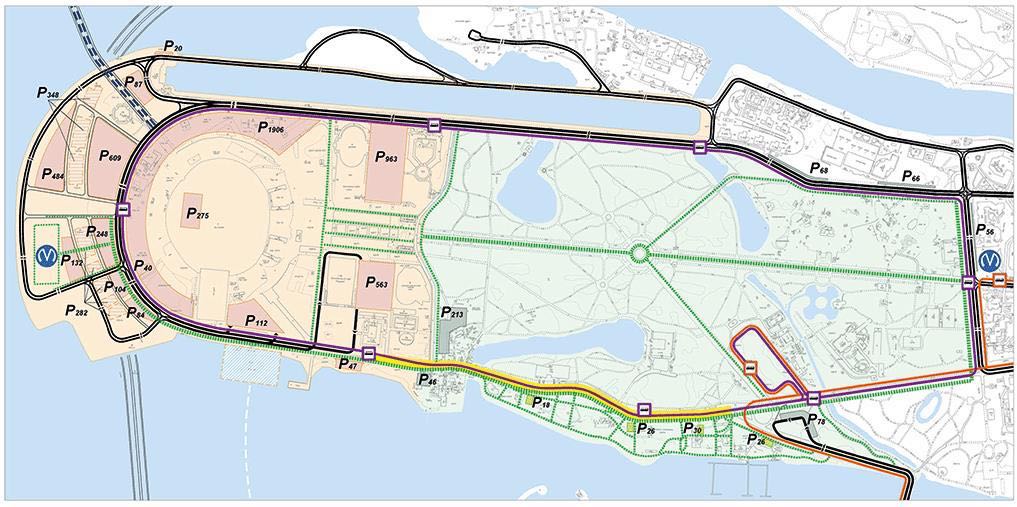

The Zenit Arena evolved into one of Russia’s most controversial projects. In December 2004, it was decided to construct a new stadium on the western part of the Krestovsky Island. In August 2007, construction started and the target date for completion was set in March 2009; however, due to numerous setbacks, the first match was only played on 22 April 2017. After Russia was awarded the organization of the World Cup in December 2010, the project gained federal prominence.

When the stadium was announced, there were numerous reasons for societal concern. Some questioned its sheer necessity . Moreover, the development of the Zenit Arena would come at the expense of the monumental Kirov Stadium, as it was planned at the exact same location. Also, the Zenit Arena was thought to damage the adjacent Primorsky Park Pobedy and residential area.

'It was so unbelievably corrupt, you cannot even start to imagine it'

Most controversy, however, emerged during the construction period. When the design was presented, construction costs were estimated at 6.6 billion rubles ($250 million). In 2016, the authorities officially announced that the final costs were 42.5 billion rubles. However, when Crime Russia added up all contracts, it reached a final outcome of 50,666,793,464.23 rubles ($1,375,366,897.74). Among the contributors was the rampant corruption surrounding the stadium, the most high-profile case being vice-governor Marat Oganesyan’s arrest for embezzling 50 million rubles. A former director of Zenit called the development of the Zenit Arena 'so unbelievably corrupt, you cannot even start to imagine it.'

'Everything that could go wrong, went wrong'

Sheer unprofessionalism resulted in many construction errors, mostly caused by sloppy works by aluminum magnate Oleg Deripaska’s Transstroy, the general contractor from 2008 until 2016. The poor quality of the retractable roof was among the biggest issues. Furthermore, the rails for the roll-out pitch had been so crookedly constructed that it failed to comply with international standards. A journalist of sports magazine Championat poignantly summarized the developments by stating that 'everything that could go wrong, went wrong.'

Flooding of the stadium in 2016 due to leaking roof (Government of Saint Petersburg, 2016)

'It is one of the most expensive stadiums in the world and there is no visible reason for that'

For cost saving reasons, the stadium was stripped off initially planned features such as lounges and facilities for courts. Some design errors have not been solved. For example, from approximately 250-300 seats, spectators are unable of seeing one of the goals. The state of the stadium remains a reason of concern to one of the interviewed urban activists: 'It is one of the most expensive stadiums in the world and there is no visible reason for that.'

Spectators were Unable to see one of the goals. This is their view during the match Zenit Saint Petersburg - SKA Khabarovsk, 13 May 2018

Spectators were Unable to see one of the goals. This is their view during the match Zenit Saint Petersburg - SKA Khabarovsk, 13 May 2018

Another reason for debate has been the exploitation of the city’s social budget. In August 2016, less than a year before the Confederations Cup, the stadium was far from completion and the budget had been emptied. Saint Petersburg’s authorities reallocated 2.6 billion rubles from the social construction budget to the stadium’s completion. Lastly, there have been rumors about exploitation of labor migrants. Allegedly, five workers died during construction. All these factors led an urban activist to conclude that the Zenit Arena is 'one of the most scandalous objects in Saint Petersburg .'

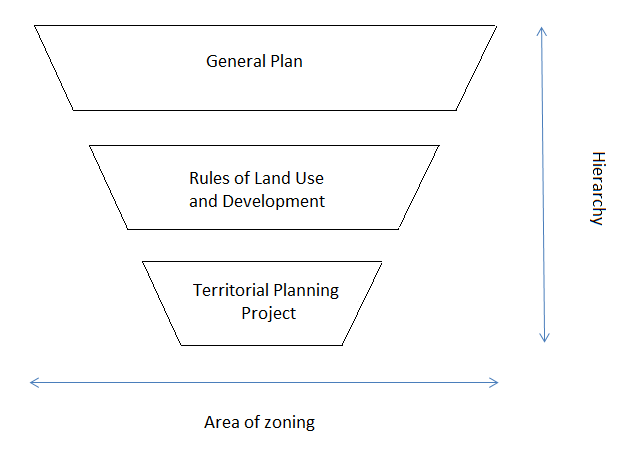

Russia’s spatial system

Russia’s spatial planning system finds its basis in the 2004 Urban Development Code, which introduced a new hierarchy of spatial documentation. General Plans remained dominant, containing a map of the functional areas of the city, boundaries and general development goals. The General Plan became the basis for a new type of documentation: the Rules of Land Use and Development, containing more specific sub-zoning, ordinances and regulation for city districts. The Territorial Planning Project establishes the zoning and development regulations of a territory within a city district.

Spatial planning structure

Legal framework

Public participation in the decision-making related to the Zenit Arena has been entrenched in the Urban Development Code and two regional laws: On the procedure for the participation of citizens and their associations in the discussion and decision-making in the field of urban development in the territory of Saint Petersburg (2004) and its successor On the order of organizing and holding public hearings and informing the public in the implementation of urban planning activities in Saint Petersburg (2006). The most significant participatory instrument is the public hearing: the authorities are obliged to publicly discuss drafts for new General Plans, Rules of Land Use and Development and Territorial Planning Projects, as well as amendments to existing documentation.

Since the development of the Zenit Arena was financed from public money, legislation on public procurements should have also been complied with. Up to 2012, legislation on public procurement did not proscribe a role for society. Then, a presidential decree and governmental order requested the organization of public discussions on public procurements exceeding 1 billion rubles. In 2013, this was anchored in Russia’s legislation by Federal Law On the contract system in the sphere of procurement of goods, works and services for providing state and municipal needs. Since 1 September 2012, Saint Petersburg’s authorities self-imposed the provisions of the governmental order on their procurement procedures.

On certain projects, this framework can be elaborated by additional laws eliminating the obligation of public discussion, as explained by a member of the expert Council for Urban Planning Activity under the State Duma Committee on Land Relations and Construction:

'Sometimes, the authorities try to realize ‘special projects’ by ‘special laws’. The construction of the stadiums for the World Cup was realized by such special law, because it was a very important project for the country’s leadership.'

This ‘special law’ was Federal Law On the preparation and holding in the Russian Federation of the FIFA World Cup 2018 and the FIFA Confederations Cup 2017 and amendments to certain legislative acts of the Russian Federation (2013), introduced to ease the organization of the World Cup and Confederations Cup by temporary relaxation of laws. The relevant amendments were adopted on 3 July 2016, in the context of the upcoming Confederations Cup. At that time, some stadiums were still far from completion, urging the authorities to hurry. The amendments introduced the inclusion of a clause in the 2013 Federal Law on public procurements, stating that this law would not apply for the '[…] procurement of goods, works, services related to […] the FIFA World Cup 2018 and the FIFA Confederations Cup 2017'.

So, the law on public procurement was temporarily suspended for contracts related to the construction of World Cup stadiums. Public discussion on procurements was only mandatory for the procurements that a) exceeded one billion rubles; and b) took place in the period between 1 September 2012 and 3 July 2016.

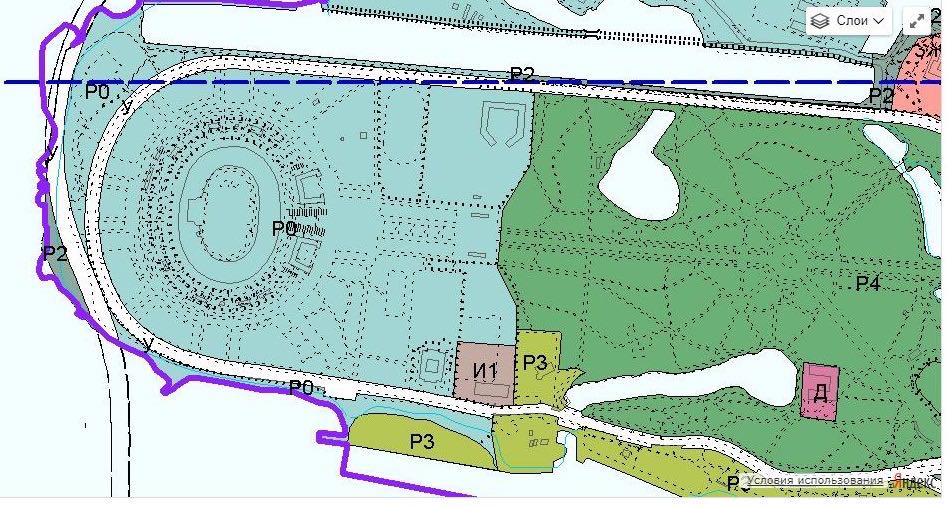

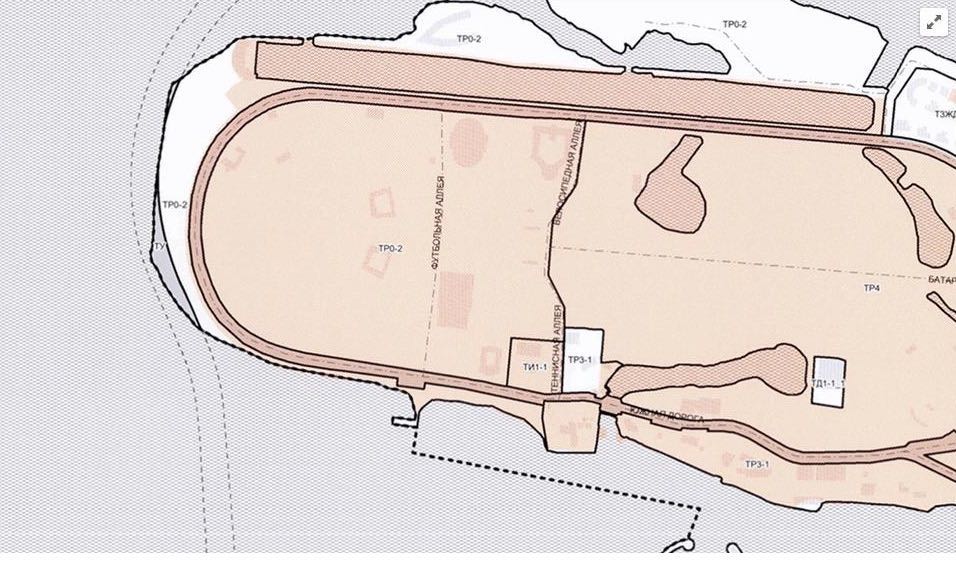

What did this legislative framework imply for the Zenit Arena? For the adoption of or amendments to spatial planning documentation, the organization of public hearings is mandatory. However, the chosen location has a remarkable peculiarity: there was already a stadium in place ‑ the Kirov Stadium - making the location very convenient: as the zoning was already equipped for a stadium, amending documentation was not necessary. Therefore, the organization of public hearings was not required.

Functional zoning of the western part of the Krestovsky Island in the General Plan (Zemelniy Vopros, 2015)

Functional zoning of the western part of the Krestovsky Island in the Rules of Land Use and Development (Peterland, 2016)

Functional zoning of the western part of the Krestovsky Island in the Territorial Planning Project (State Research and Design Center of Saint Petersburg General Plan, 2007).

Functional zoning of the western part of the Krestovsky Island in the Territorial Planning Project (State Research and Design Center of Saint Petersburg General Plan, 2007).

The organization of public discussions on public procurements was mandatory for procurements exceeding one billion rubles that were concluded between 1 September 2012 and 3 July 2016. Only four out of forty-six procurements met both conditions, so most procurements did not have to be publicly discussed.

Contracts to be subjected to mandatory public discussion

|

Contract nr. |

Date |

Value in RUB |

Description |

|

0172200002613000184 |

19 November 2013 |

12.3 billion |

Contract with Transstroy on the completion of the stadium. |

|

0172200002614000244 |

6 November 2014 |

1.8 billion |

Contract with Transstroy on the adaptation of the Primorsky Park Pobedy to the modern use of a corridor to the new stadium |

|

0172200002614000248 |

10 November 2014 |

7 billion |

Additional contract with Inzhstransstroy-SPB (Transstroy’s regional branch) on the completion of the stadium |

|

2783000234216000036 |

6 April 2016 |

1.8 billion |

Contract with LEOKAM on the construction of control posts and entrance gates |

The authorities’ attitude towards engaging society

Even more telling than the legislative framework, has been the actual organization of public hearings. The decision to construct a new stadium could be made without consulting the public and the authorities chose not organize public hearings. This decision was taken in full compliance with legislation and documentation, thus legally there were no objections. However, morally, the decision not to engage the public can be considered dubious. The reason why it is not necessary to engage the public when spatial developments do not require amendments to the zoning, lies in the assumption that the character of the space will not be altered too much as long as the proposed development fits in the current zoning. Although technically the Kirov Stadium and the Zenit Arena share the same function, in reality the regular use of the two stadiums differed greatly. Whereas the Kirov Stadium had been out of use for a decade, the Zenit Arena should regularly attract up to 60,000 football fans and concert visitors, with all consequences for the surroundings (e.g. traffic congestion, trash, noise). Thus, although not legally required, publically discussing the plans could be considered ‘the right thing to do’.

Over the entire course of development, there were only three public hearings related on zoning issues on the territory: on 19 March 2007, when temporary regulations were to be introduced; on 30 June 2014, when amendments to the Territorial Planning Project were proposed; and, also on 30 June 2014, regarding land surveying. However, neither of these hearings addressed the object of the Zenit Arena as a specific topic.

For four procurements, public discussions were obliged by legislation. However, the only procurement for which evidence of a public hearing is available, concerns the 12.3 billion rubles contract with Transstroy for completion of the stadium. The tender for this contract, in which Transstroy was the only participant, was organized on 1 November 2013 and the first (digital) stage of the public discussion took place from 2 to 6 October. The second stage of the public discussion – the public hearing – was conducted on 11 October.

'All these events are not real'

Moreover, the organization of public hearings per se does not automatically engender public participation. According to the interviewees, public hearings can be manipulated in at least five ways. A first method is to ensure a low turnout by deliberate miscommunication. 'There are such abuses when they hide information and do not inform the public about meetings.', said the initiator of Beautiful Petersburg, Saint Petersburg’s largest civic platform for spatial issues. As legislation does not stipulate in which printed media public hearings should be announced, the chosen outlet might be a paper with very low circulation. A local spatial planning lawyer argued that deliberate miscommunication is a big problem: 'Sometimes it is not easy to find out about upcoming public hearings. They can announce a public hearing in some small newspaper and you will never know about it.'

A second way to manipulate public participation, is by organizing public hearings on inconvenient dates and times. Occasionally, public hearings are organized during working hours or on special days – such as 1 September, the traditional start of the school year.

Furthermore, public hearings can be manipulated by the choice of the venue. Legislation does not stipulate a minimum size of the venue and deliberately opting for a venue that is too small to host all the interested parties is a widespread practice. In Saint Petersburg, this occurred when the Gazprom skyscraper was being discussed.

Fourthly, Russian authorities are suspected of paying participants to express loyalty to the authorities’ plans, by direct payments, raising their pensions etc. Although impossible to verify, hiring of civil servants, students, societal ‘activists’ and other 'grey mice' (quoting a former director of Zenit) is considered a widespread practice:

- 'to occupy all spots in the room and exclude critical participants' (interview member of the expert Council for Urban Planning Activity under the State Duma Committee on Land Relations and Construction

- 'to support any proposal made by the authorities.' (interview initiator Beautiful Petersburg)

- 'to manage a majority.' (interview city architect)

Lastly, public hearings may be steered by subjective consideration of comments and proposals made by participants. The authorities easily ignore comments and proposals that are not in line with their own plans. These manipulative practices led a representative of one of Zenit’s fan clubs to conclude that 'all these events are not real.'

The expert-elitist attitude

The authorities’ attitude towards engaging society, is best described as expert-elitist, characterized by distrust towards societal actors. Authorities do not view civil society as an equal partner that they can negotiate with, as an urban activist argued: 'They see these people as a strange mass of stupid people who do not know what they are talking about. Government representatives just do not believe it is possible to talk to this folk.'

In some projects this expert-elitist approach is more dominant than in others. Depending on the significance of the project, there are remarkable differences regarding openness and level of public engagement in different projects. In decision-making processes on the level of the neighborhood, there is a considerable level of pluralism, public participation and constructive dialogue. On issues where the political stakes are higher, such as the Zenit Arena, decision-making process is less open and transparent.

Societal attitude

Civil society had been very aware of all developments, concerns and wrongdoings related to the Zenit Arena. Despite this awareness and accuracy by which urban activists, stakeholders and passersby could reminisce the narrative of the stadium, this did not lead to any real activity. Particularly interesting in this respect is the societal response to the corruption scandals. Civil society appears to be so acquainted with corruption that it does not trigger public outcry:

- 'People think that there is so much corruption that you cannot do anything.' (coordinator Living City, NGO dealing with cultural preservation)

- 'I was not shocked by the corruption. In Russia, they usually steal.' (initiator Beautiful Petersburg).

- 'People will go out on the street if they will be restricted to grill. Not for abstract things like corruption.' (urban activist Center of Independent Social Research).

'People will go out on the street if they will be restricted to grill. Not for abstract things like corruption'

The only public domain in which society expressed its opinion on the Zenit Arena, was the internet. The Zenit Arena became a popular topic of online mockery, particularly concerning corruption, construction mistakes and delay. 'People protest, but people protest from their sofas', concluded the coordinator of Living City.

'Piter in 2050' (Fishki, 2016).

Formal participation

This lack of public interest in actively engaging is demonstrated by the absence of participation in the four public hearings. None of the respondents, including direct stakeholders and urban experts, was able to reminisce any public hearing. 'I never heard that there were public hearings. That is a surprise for me. Even in the expert community, I have never heard of this, ' said an urban activist for the Center of Independent Social Research.

'I have never heard that there were public hearings. That is a surprise for me'

Low awareness translated into an extremely low turnout in public hearings. At the public hearing on the amendments of the Territorial Planning Project, only two civilians showed up, leading one of them to question the validity of the hearing:

'The Chkalovskoe municipality has 22,000 inhabitants. There are only two people here, so I think that there is no reason to recognize this public hearing as valid.'

However, according to the authorities, the number of participants was irrelevant:

'The number of participants is not established by law. The procedure for conducting hearings is fully observed. We believe that there is no reason to recognize public hearings held as not in accordance with the law.'

The public hearing on the procurement of the contract with Transstroy was organized on 11 October 2013. According to the authorities, 'based on the results of the open public hearing, it was decided to continue the procedure for placing the order without making changes.' In reality, not a single civilian showed up. The hearing was organized as the second stage of public discussion within the legislative framework of public procurement. The online discussion took place from 2 to 6 October and received only one comment: a user with the nickname ‘kolomen23’ answered ‘yes’ to all questions.

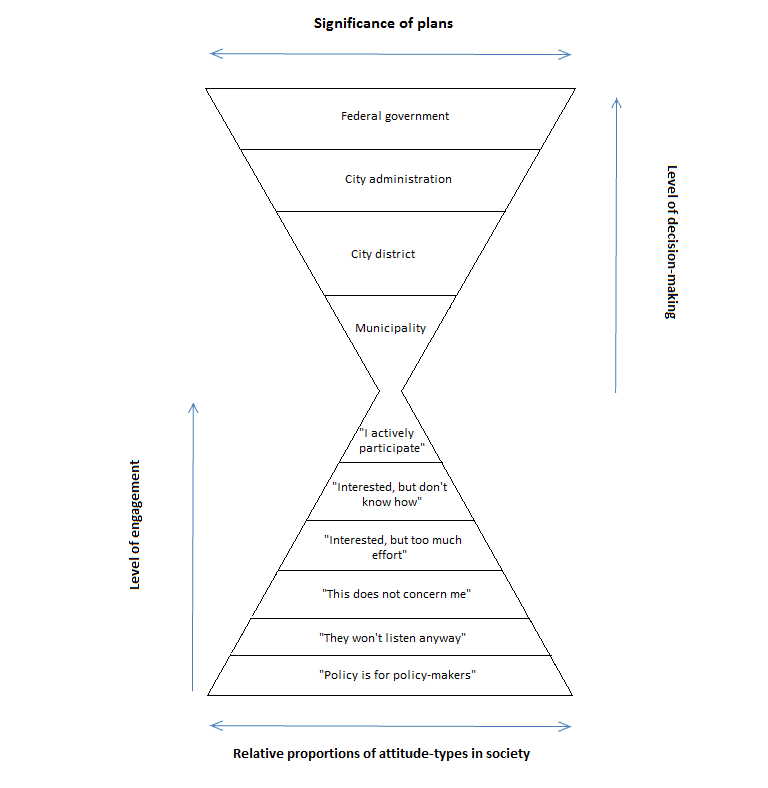

Six types of public attitude towards participation

Societal attitude towards engaging in formal governance processes can broadly be classified in six categories. The 'policy is for policy-makers'-type believes that policies should be drafted by a professional elite, since ordinary civilians lack knowledge and are therefore not entitled to participate. 'Why should I participate? I am not a planner, nor an architect,' said a passerby when asked about participation. According to the coordinator of Living City, 'people want someone to take the decisions for them. They always want some kind of tsar.'

The 'they won’t listen anyway' -type is skeptical towards institutionalized participation. According to this group, participating is useless as they feel that the authorities will not allow them to genuinely contribute. 'Many people do not want to be part of bla-bla-bla demonstrations,' said the urban activist for the Center of Independent Social Research.

The 'this doesn’t concern me'-type is only interested in participating in matters in which someone has a direct interest; issues such as corruption and wasting of public money are considered too opaque to be of direct concern.

The 'interested, but too much effort'-type is intrinsically interested to participate, but fails to do so because there are too many obstacles. In particular, lack of time is considered a reason not to participate.

The 'interested, but don’t know how'-type is willing to engage, but frustrated to do so by a lack of knowledge and experience. Despite their intrinsic motivation, these people are deterred by the bureaucratic nature of formal decision-making processes: it simply is too difficult to find out how.

Lastly, there it the 'I actively participate'-type. There are two types of spatial projects that yield significant public participation: spatial objects that directly infringe upon people’s lives; and spatial objects that endanger the identity of the city. 'Topics of interest can be very elementary. A mother walking in the park with her baby, finding there are no benches to rest. Someone who is drinking a coffee to go and cannot find a garbage bin on the street. Infrastructure. People show real interest in these low-level problems,' explained the initiator of Beautiful Petersburg. The high degree of public participation in such projects has two explanations. First, as such projects are very relatable, public interest is high. Second, the low significance of such projects implies that entry barriers to participate in decision-making are low. The other projects that spark above average public engagement, are projects that are considered to damage the city’s identity. The Gazprom skyscraper was the most iconic example of such; in the words of a professor at Moscow Higher School of Economics, the demonstrations were 'bigger than anything' and the initiator of Beautiful Petersburg referred to it as 'the second revolution, after the one in 1917.'

Although these topics seem to appeal, the 'I actively participate'- type remains marginal in the city. Beautiful Petersburg is the biggest spatial developments-related civic platform in the city. Its VK group enjoys approximately 55.000 followers and up to 100.000 people can be reached. Although not insignificant, in a city of approximately five million inhabitants, this is still marginal.

Relationship between state and society

The conclusions of this research can be incorporated in the model of an hourglass society, in which civil society and authorities are two separated entities with a clear role division and a small area of interaction. The lower half of the hourglass displays the biggest obstacle to public participation on the side of the public: the more participatory the attitude, the smaller the relative proportion of this attitude in society. Interaction between society and state takes place in the area where the top of the bottom half (the 'I actively participate'- type) meets the bottom of the top half (the municipal level of decision-making). As the level of significance of the spatial project increases, decision-making is distanced further from society.

Hourglass society

The development of the Zenit Arena demonstrates that the extent of public participation in Russian governance networks depends on two factors: tolerance of the authorities towards society and society’s affinity with a project. On the side of the authorities, there is an expert-elitist approach to decision-making based on an overall distrust in civil society’s capacities, as well as on the significance of a project to the elite. However, the absence of public participation in the decision-making concerning the Zenit Arena cannot solely be attributed to this expert-elitist attitude. Societal interest to engage was extremely low, as the turnout at public hearings demonstrates. In conclusion, the case of the Zenit Arena demonstrates that both authorities and civil society lack the vital interpersonal trust necessary to make decision-making genuinely participatory.

References

Fishki (2016). Response in society to the construction of the Zenit Arena. https://fishki.net/2179534-reakcija-socsetej-na-stroitelystvo-stadiona-zenit-arena.html

Government of Saint Petersburg (2016). Implementation of the project 'Design and construction football stadium in the western part of the Krestovsky Island with dismantling of the existing structures of the stadium. Kirov at the address: Krestovsky Island, South Road, 25'. https://www.gov.spb.ru/static/writable/ckeditor/uploads/2016/08/23/%D0%9F%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B7%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F%20%D0%BA%20%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%84%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%B8.pdf

Levada (2016). The participant in the policy. https://www.levada.ru/en/2016/09/05/the-participant-in-the-policy.

Peterland (2016). Territorial Planning Projects of Saint Petersburg. http://www.peterland.info/pzz/.

State Research and Design Center of Saint Petersburg General Plan (2007). Territorial Planning Project and land surveying project of the western part of the Krestovsky Island. http://gugenplan.spb.ru/ru/541.

Zemelniy Vopros (2015). General Plan of Saint Petersburg. https://www.zemvopros.ru/genplan.php

This master thesis can be read in full here.