In 2019, the outcome of a hard-fought battle over the structure of the Eastern Orthodox Church shook Ukrainian religious life to its core. For years, the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow had not recognised the autonomy of a separate Kyiv-based church, instead only recognising their own branch, the Moscow Patriarchate. When the Patriarch of Constantinople finally recognised and granted independence to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in January 2019, many Ukrainians saw the decision as an important victory and further consolidation of the country’s independence. In this thesis Elsa Court examines what happened to parishes in western Ukraine as they were faced with the choice to switch to the new Kyiv-centred church or stick with the politically unpopular Moscow Patriarchy.

People in Kyiv celebrate the unification of Orthodox Church of Ukraine in December 2018 (Photo: Twitter).

by Elsa Court

Since the formation and granting of autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) in 2018-19, the country’s historically larger Orthodox denomination, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate (MP), has come under significant pressure. Unlike the OCU, the MP is part of the Russian Orthodox Church structure and is therefore deemed a threat by many political elites. However, the MP does have extensive autonomy from Moscow in administration, financial issues, and the election of its own primate, and ethnic Ukrainians dominate among both the leadership and membership of the Church.[1] Nonetheless, its hierarchical subordination to the Moscow Patriarchate means there is growing distrust over the ‘Russian’ orientation of this Church in independent Ukraine.

In the run-up to the Presidential Election in March/April 2019, incumbent President Petro Poroshenko centred his campaign around Ukrainian patriotism. With the slogan ‘Army, Language, Faith’, he pushed for the recognition of a single national church in opposition to the MP, thereby increasing religious tensions. Although he lost the elections to Volodymyr Zelensky, he won this religious war, and as many as a third of his voters chose to support him because of his role in the OCU being granted autocephaly. In many communities, however, locals came into conflict when they had to decide whether they wanted to stay with the MP or switch to the OCU. This thesis discusses the main reactions to this conflict in local churches in Rivne oblast (western Ukraine).

Local Orthodox church in Chudel, Rivne Oblast. Photo: Elsa Court.

Three Churches in Ukraine

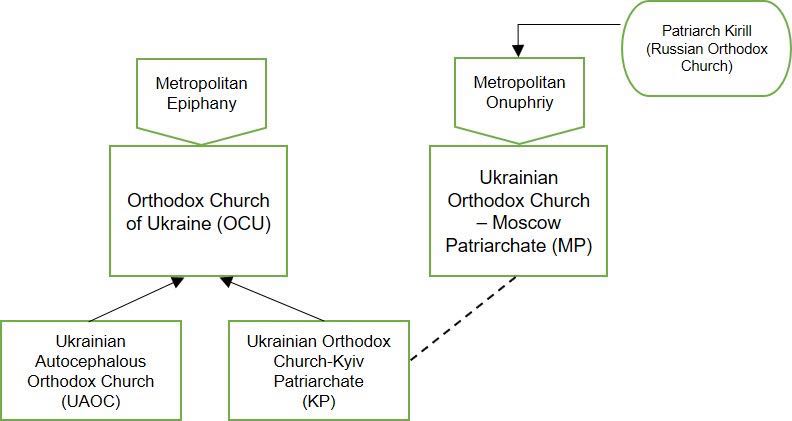

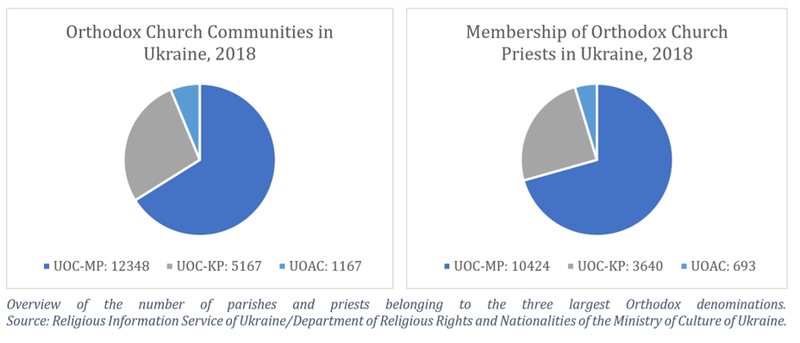

Until recently the religious landscape in Ukraine was fragmented between three branches of Orthodoxy: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate (MP), the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate (KP), and the smaller Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC). The Kyiv branch split from the Moscow branch in the 1990s, initiated by Metropolitan Filaret when the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became independent. He has since been involved in numerous attempts to unite the churches under his leadership and both sides of the schism have competed for favour with the government.[2] The church leadership in Constantinople, meanwhile, preferred to stay out of the fight.

In terms of registered communities (i.e. parishes), the MP was long considered the largest, with over 12.000 recorded in 2018. Yet in terms of Ukrainians’ confessed affiliation, polling data shows that 28% of Ukrainians adhere to the Kyiv Patriarchate, and just 12% to the MP.

Politicisation of religion

The differences between these denominations have little to do with belief or practice. Instead, ‘they hinge on the different authority figures each recognises’ – the religious leadership based in Moscow or Kyiv.[3] The Euromaidan Revolution, however, politicised this difference more than ever before.

During Euromaidan, the KP openly supported pro-European protesters, converting the nearby St. Michael’s Monastery into a hospital and morgue. The MP, however, found itself in a more complicated position, as it had received considerable support under President Yanukovych. Their leadership sometimes supported Yanukovych, and often made no statements at all.[4] However, many members of this church, as well as a considerable number of priests, were active on the Maidan alongside clergy of all denominations. They stood between lines of riot police and protesters in last-ditch attempts for peaceful resolution and remained on the square to perform the funeral rites for civilians who had been killed.

Eventually, in February 2014, the UOC-MP issued a statement that ‘under no conditions can the authorities shoot peaceful civilians’[5] but the gap between the official stance of the Church and the actions of the clergy and believers was already putting huge pressure on its relationship with Moscow. The cracks only widened when the military conflict began in Donbas, as priests of all churches became army chaplains, gathered humanitarian aid, and prayed for the nation of Ukraine in their sermons, while a number of high-level UOC-MP clergy spoke in favour of the occupation of Crimea and some MP priests in Donbas openly supported separatists. At the same time, Patriarch Kirill’s close relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin was under scrutiny by critics of the MP.

In this context, many Ukrainians began to switch from affiliation with the MP to the Kyiv Patriarchate, and support grew for the granting of autocephaly to a united Ukrainian church. According to a March 2017 survey, the proportion of self-reporting affiliation of Orthodox believers to the MP fell from 34.5% in 2010, to 17.4%. Meanwhile, those reporting to affiliate with the Kyiv Patriarchate rose from 22.1% to 38.8%.

Religious decree gave Ukraine autocephaly

The situation culminated in a council of bishops in December 2018 in Kyiv, which decided on the unification of the Kyiv Patriarchate and the smaller UAOC, thereby creating the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU). Most of the clergy of the MP boycotted the council.

On 5th January 2019, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople granted the OCU a Tomos. This document is a decree of independence, or official recognition of the newly formed church. In response, the Russian Orthodox Church cut off ties with Constantinople and continues to view the OCU as completely illegitimate.

Much of the reporting on this schism focuses on the (geo)political roots and implications of these events, on the positive impact on Ukraine’s nation building project, and on the way politicians both in Kyiv and Moscow have turned to religion to score political points. However, little attention has been paid to how this affects the lives of average Orthodox believers in Ukraine.

Supporters of the MP propose that the run-up to the Presidential elections polarised the country’s religious landscape. In their opinion, Orthodoxy has remained unchanged for centuries; switching over to a new church that appears to be engineered by politicians appears to be the ultimate blasphemy.

For others, the conceptualisation of the OCU by figures like (former) President Petro Poroshenko as the ‘national’ church is attractive and represents a long-awaited Ukrainian church for the Ukrainian people.[i] For them, the OCU represents the new Ukraine, a country truly separated from Moscow.

Although Ukraine is constitutionally secular, many politicians encouraged parishes to switch from the MP to the new ‘national’ Church, framing the ‘Moscow’ church as pro-Russian and a threat to national security. Parishes were forced to make a choice between ‘switching’ from the MP to the new united Ukrainian church, or face scrutiny at remaining with an ‘unpatriotic’ church. By January 2020, Metropolitan Epiphany said that around 600 of the previously mentioned MP parishes had ‘switched over’ to the new Orthodox Church of Ukraine. However, data remains contentious and as this thesis will show, ‘switching’ is a legally vague process.

How did local churches react to the creation of the OCU?

This thesis examines what happens when daily life becomes political, leaving some communities to abruptly end up on the ‘wrong’ side of a newly-emphasised boundary. It explores the various scenarios that MP parishes underwent in the north-western province of Rivne, in order to understand the complex process of boundary formation and negotiation at a local level, with differing results. It thereby seeks an answer to the question: how did rural Moscow Patriarchate parishes in the Rivne Oblast (province) react to the activation of religious boundaries at a national level, following the unification of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in 2018?

The focus is on rural communities for two reasons. First, rural areas in Ukraine have much higher religiosity rates, thus religion is a more important organiser of social life. For this reason, the activation of religious boundaries has a greater impact on villagers.[ii] Secondly, smaller communities usually only have one house of worship, meaning the question of switchover leaves little opportunity for compromise.

From the start, it was clear that each MP parish reacted differently – some coped well, negotiating dialogue or even a calm transition of the church to the OCU, whereas others experienced violent confrontation and unresolved conflict, as parishioners clashed with each other or with their priest over perceived allegiances. Therefore, although this thesis focuses on how communities reacted, it also discusses which factors cause or mitigate local conflict.

Roughly speaking, there were four types of reactions of rural MP parishes following the unification of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. To visualise these, I plotted the scenarios in the following matrix:

Scenario matrix of rural MP parishes reactions[iii]

|

SCENARIO |

Parish switches to OCU |

Parish does not switch to OCU |

|

No open or visible conflict between local actors |

Agreed-upon switchover |

Status quo with coping mechanisms |

|

Open conflict between local actors |

Contentious switchover |

Ongoing conflict |

The matrix boxes represent a continuum of reactions rather than four clear-cut scenarios. Conflict can range from arguments and verbal abuse to physical violence. Moreover, it can be difficult to know whether or not a switchover happened within my timeframe, as I limited my focus to the immediate impact. In fact, I did not find a clear case of a parish in the Rivne Oblast that made a contentious switchover to the OCU without some degree of an ongoing conflict. While the church building itself may have been used for OCU services, at least part of the population would use another building in the village for MP services.

This thesis looks at three of the scenarios: ‘open conflict’, ‘agreed-upon switchover’, and ‘status quo with coping mechanisms’. I used secondary sources for the first two, and for the case of ‘status quo with coping mechanisms’, I visited an MP parish (Chudel) that I was previously familiar with to gather data.

A religious struggle?

Like many civil conflicts that appear to be informed by religion, the struggle was not about religion itself. Rather, it was about political power, economic resources, or symbolic recognition.[6] This reflects the idea that while a ‘master cleavage’ may drive conflict, local actors use the label of religious conflict, for example, to settle personal grievances and private enmities.[7]

Therefore, local-level conflict can reflect a different reality than the national-level one. Religion has the power to define symbolic boundaries, and institutions can draw boundaries around or between religious affiliations, which can rupture social cohesion. This leads to the question of how, when, and why the (religious) boundaries that define ingroups and outgroups shift or become more or less pronounced.

Local Orthodox Church in Rivne Oblast, Ukraine. Photo: Elsa Court.

Local Orthodox Church in Rivne Oblast, Ukraine. Photo: Elsa Court.

Results of Analysis

Case I: Derazhne (Agreed-Upon Switchover)

It initially appears that in Derazhne, the process moved incredibly swiftly and with no visible conflict. The churchwarden claimed around 300 people were present at the vote on 7th January 2019 (Orthodox Christmas Day) at the church, and they unanimously voted to switch to the OCU. [8] This is not to say there was no one who disagreed, but no disagreement was voiced publicly to the media or through the voting process. The priest refused to speak on camera to journalists, citing pressure from ‘above’, inferring his superiors in the church.[9] Though it was the first reported switchover in Rivne Oblast, a transition from the MP to the Kyiv Patriarchate had been previously attempted in 2015, but was halted after MP representatives visited the priest, and he decided to delay this decision.[10]

In this context, the granting of autocephaly and state endorsement of the OCU in 2018-19 acted as a catalyst for a contested process that had been ongoing for at least four years. The long-term process also may explain the reaction of the community of seemingly unanimous support, at least on a surface level, as the change had not happened overnight.

Language issues

A second factor that may have that limited contention in the community’s reaction concerns the issue of language. One of the key differences between the services of the two denominations is the language used in the liturgy – in the MP the liturgical language is Old Church Slavonic, whereas in the OCU, it is Ukrainian. The language issue often broadens the divide between parishioners who support the MP and those who want to transition to the OCU.

The priest in Derazhne had been conducting services in Ukrainian since 1995, even though he was ordained in the UOC-MP.[11] Following Euromaidan and the ongoing war, ‘Ukrainian is valued not only for its communicative functions but also for its symbolic role as the national language’.[12] It is possible that the long-term nature of the decision to switch, as well as the language situation, minimised the possibility of conflict between actors. It therefore demonstrates the importance of the village’s social and historical context.

Case II: Nova Moshchanytsia (Contentious Switchover/Ongoing Conflict)

In exploring how the community reacted, it should be reiterated that there were two separate votes held on the switchover, which ended in different results. The first was held in the church and those partaking voted to stay with the MP, whereas the second took place in the village hall, and resulted in a vote for a switch to OCU.

Tensions first arose after these meetings, and this demonstrates how vague legal language can create confusion and conflict within communities (see endnote ii). However, it cannot be excluded that the situation acted as a ‘master cleavage’ and was used to settle local scores, which can only be investigated by long-term fieldwork.

Within timeframe of my research, conflict was limited to verbal aggression and confrontation as villagers clashed over the physical property of the church. Both sides felt a constant threat of violence, and called on those from outside the community to come to the village to support them. The residents who wanted to remain with the MP reacted with anger, to the extent that they mobilised others in the region and protested outside the regional administration in Zdolbuniv.

Case III: Chudel (Status Quo with Coping Mechanisms)

Fieldwork in Chudel uncovered various coping mechanisms that likely kept the community peaceful. I wanted to interview the priest to hear his perspective, but he initially declined. He was wary of discussing anything to do with the situation with me, and this hesitation to talk about the religious situation with me was also reflected in the ordinary population. They also refused to speak about it with me, as they ‘didn’t want to talk about politics.’ The priest and others considered the topic to be sensitive, and wanted to minimise the risk of provoking conflict, which so far had not affected Chudel.

Towards the end of my time in Chudel, my host had convinced the priest (Father Serhii) to speak to me, allowing an interview after the Sunday service. I asked him how he talked about the issue with those who supported a switchover. He told me that he took the initiative to have open discussions with the community, immediately after the unification council meeting in Kyiv in December 2018, which created the new church.

‘I initiated this discussion with people to have a conversation, to find out what people thought and their different views, their attitudes. And I laid out not my opinion, but the facts of what had happened[…]so that I could hear the opinions of people, what their position was.’

Consequently, it appears there are two mechanisms at play: while the natural reaction, at least to outsiders or on an ‘everyday’ level, is to avoid the topic completely, the priest also reacted in a way that tackled the issue head-on through dialogue. Therefore, how (or whether) the issue is discussed is the result of a distinction between different relationships between actors: the issue may be less likely to be discussed among locals than between locals and their priest.

While the events were perceived as controversial (as evident from the priests reference to the ‘so-called’ council), the priest felt it as necessary to speak with his parishioners about their concerns. He told me that this strategy of dialogue was not easy, and other priests had not taken such initiatives:

‘I communicated with neighbouring priests and they have not talked and in all this time, there are tensions, and so they don’t know, how people are concerned, what are their perceptions. I immediately decided to openly discuss, because every person has their own thoughts and on social media there is also a discussion. They listen to my position and I listen to their position.’

He therefore agreed that dialogue was an important strategy to minimise conflict, underlining that it was crucial to ‘set out immediately’. The quote above also demonstrates that while there was no open conflict, he was aware that there may have been more heated exchanges on social media that can undermine social cohesion. His focus on engaging in conversation with his parishioners, even if they have opposing views that they do not openly talk about, may therefore be an important factor that limited confrontation within the community.

Silence to evade conflict

I asked Father Serhii if he was aware of any parishioners saying that he was ‘pro-Moscow’ or ‘pro-Russian’, and he answered:

‘So far I have not encountered that in my life. But firstly, it’s an opinion and maybe some people have that opinion of me. But I don’t disagree that these thoughts exist, I could even say I am sure that they are there. Maybe that is due to the fact that I have so far not compromised faith (…) Maybe it’s because of that, but I don’t know. But so far I have not heard it with my ears, but I am sure that it is there.’

Silence is a relatively under-studied mechanism of averting conflict, perhaps due to the negative connotations the word has within the field of conflict studies and human rights, where ‘silence’ is often linked to collective amnesia (forgetting). However, in some contexts silence can be a useful tool in societies that are vulnerable to conflict, since the absence of any reference to a certain word, phrase, or insult may prevent tensions from boiling over. In this sense, silence is a form of strategic politeness.

Local identity

A final potential factor is related to the topic of local identity. It is important to note that regionally, the northern half of Rivne Oblast had not seen considerable contentious reactions. My first question to the local priest concerned why the politicisation of religion had not inflamed tensions in the village, in the way it had in others that created conflict.

‘It’s hard for me to say why. Firstly, my feeling is that here in Polissia, the people you find are altogether different compared to there, such as in Dubno or Volyn. Here people are, well, more kind hearted, understanding, in this sense they are educated and more peaceful, than in Dubno or Ostroh. Here we have many spiritual people.’

The first factor that came to Father Serhii’s mind was therefore the distinct identity of not just the village, but the surrounding area, which is known as Polesia (transl: along the forest). This historical region lies along the border of Ukraine and Belarus, stretching from the border with Russia in the east to where Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland meet in the west. However, only the northern half of Rivne Oblast is considered to be part of Polesia – the area around the cities of Rivne, Dubno and Ostroh lie outside the boundary.[13] Later in the interview, Father Serhii referred back to the difference between the area around Chudel and other parts of the oblast, saying:

‘Here there are many religious people, good and righteous ones […] Of course, there are different people, but this is the majority. When I arrived here in 1992 that was right away a large, cardinal difference that I saw. People from Rivne to the west and between Rivne and here, there is a large difference.’

Father Serhii’s words may point to regional identity as a factor which helps to prevent conflict. This is not to say that there were no religiously-informed conflicts in Polissia, but a sense of sub-national identity may have been used to limit conflict and defer blame to Kyiv. This is potentially reflected in the local discourse as the religious situation was often labelled as ‘politics’, putting the matter at a distance and blaming it on the manipulation of political actors in Kyiv. However, this hypothesis would require in-depth research through further fieldwork.

Conclusion

This thesis sought to answer the question of how rural Moscow Patriarchate parishes in Rivne Oblast reacted to the activation of religious boundaries at a national level, following the unification of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in 2018. Focusing on three cases in one region of Ukraine revealed the importance of the role of priests and the local authorities in determining the reaction of a community.

However, it should again be underlined that this research was exploratory and thus limited in terms of number of cases, geographical scope, and timeframe. The long-term impact of the unification of the OCU still needs to be assessed, particularly within the context of a change of President. In this sense, there are still further questions. For example, the puzzle of why in some districts (raions), regional administrations became deeply involved in local religious affairs, whereas in others their presence was hardly noticed, remains to be explored.

In tackling the question of how MP parishes reacted locally to the activation of religious boundaries, this thesis shows how decisions made in the political centre can unpredictably impact lives on the periphery, and shows that the unification of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine was not simply accepted across the country overnight. Focusing on rural areas, a demographic often ignored when considering structural level changes, allows for a more comprehensive understanding of Ukraine’s evolving religious landscape, and in turn, its social boundaries beyond the east-west dichotomy.

This master thesis can be read in full here.

Notes

[i] Although Poroshenko failed to win a second term, statistics show as many as a third of his voters chose to support him because of his role in the OCU being granted autocephaly. See: ‘Svezhiy opros: Stalo izvestno o reitingakh Zelenskogo i Poroshenko’, Hvilya.net, 11 April 2019, https://hvylya.net/news/exclusive/svezhij-opros-stalo-izvestno-o-rejtingah-zelenskogo-i-poroshenko.html?fbclid=IwAR2lMihlHJq1_IardPAXjb2YJ0DhUFxAyy7qq__hRFSHv9M4357ASlPT1Fc.

[ii] I use the word ‘villagers’ and ‘parishioners’ interchangeably in this thesis, use the word parishioner in terms of someone living within the village parish, rather than in the sense of a regular churchgoer (though some are).

[iii] In terms of defining ‘switchover’, the law (no. 4128/D, which came into force January 31st 2019) states that a transition requires a vote by a two-third majority by the church community, and that there must then must then be a legal re-registration of the religious community, under the new church (the law does not clarify who belongs to the ‘church community’, and therefore who has the right to vote). Those who voted against a switchover have the right to form their own religious community. In terms of property, the ‘church community’ remains the owner and user of the church building, though in the case of a split into two religious communities, an agreement should be arranged as to the alternate use of the church.

References

[1] Katarzyna Jarzyńska, ‘Patriarch Kirill’s Game over in Ukraine’, OSW Commentary (Warsaw: Centre for Eastern Studies, 14 August 2014), https://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/commentary_144_0.pdf.

[2] Cyril Hovorun, ‘Churches in the Ukrainian Public Square’, Toronto Journal of Theology 31, no. 1 (2015): 6.

[3] Catherine Wanner, ‘“Fraternal” Nations and Challenges to Sovereignty in Ukraine: The Politics of Linguistic and Religious Ties’, American Ethnologist 41, no. 3 (2014): 432.

[4] Cyril Hovorun, “Churches in the Ukrainian Public Square,” Toronto Journal of Theology 31, no. 1 (2015): 6.

[5] Shlikhta, “Eastern Christian Churches Between State and Society: An Overview of the Religious Landscape in Ukriane (1989-2014),” 138.

[6] Brubaker, ‘Religious Dimensions of Political Conflict and Violence’, 4.

[7] Stathis Kalyvas, ‘The Ontology of “Political Violence”: Action and Identity in Civil Wars’, Perspectives on Politics 1, no. 3 (2003): 476.

[8] ‘Persha hromada UPTS (MP) na Rivnenshchyni perei’shla do PTSU’, Radio Svoboda, 8 January 2019, https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/news-persha-hromada-upts-mp-na-rivnenshchyni-pereishla-do-ptsu/29697376.html.

[9] Anna Yatsuk and Volodymyr Zakharov, ‘Z MP u PTSU: hromada na Rivnenshchyni zminyla tserkovnu iurysdyktsiiu’, Rivne 1, 10 January 2019, https://rivne1.tv/news/z-mp-u-ptsu-hromada-na-rivnenshchini-zminila-tserkovnu-yurisdiktsiyu-video.

[10] ‘Bor’ba za khram na Rovenschine: svyaschennik posle obscheniya s predstavitelyami UPTS MP poteryal soznanie’, Novosti Rovno, 30 June 2015, http://topnews.rv.ua/other/2015/06/30/36596.html.

[11] Yatsuk and Zakharov, ‘Z MP u PTSU: hromada na Rivnenshchyni zminyla tserkovnu iurysdyktsiiu’.

[12] Volodymyr Kulyk, ‘Language and Identity in Ukraine after Euromaidan’, Thesis Eleven 136, no. 1 (2016): 98.

[13] Anatoliy Melnychuck, Oleksiy Gnatiuk, and Mariia Rastvorova, ‘Use of Territorial Identity Markers in Geographical Researches’, SCIENTIFIC ANNALS OF „ALEXANDRU IOAN CUZA” UNIVERSITY OF IAŞI 60, no. 2 (2014): 166.