While there is a rich body of Ukranian literature, dating back as far as any other in Europe, it has been mostly undiscovered. Why has Ukraine's literature barely penetrated the broader world literary consciousness, and what has changed since 2022? Uilleam Blacker, associate professor at UCL and a literary translator specializing in Ukrainian and Eastern European culture, provides a short history of the suppression of Ukrainian literature and gives an extensive overview of contemporary works as well as classics worth reading.

Special force serviceman stands guard near a monument of Ukraine's national poet Taras Shevchenko in Borodyanka, damaged during the Russian invasion. Photo: Oleg Petrasyuk | ANP | EPA

Special force serviceman stands guard near a monument of Ukraine's national poet Taras Shevchenko in Borodyanka, damaged during the Russian invasion. Photo: Oleg Petrasyuk | ANP | EPA

By Uilleam Blacker

In late February 2022, editors and publishers around the world scrambled to find Ukrainian authors who might explain the poorly-understood European country that suddenly found itself in the global spotlight. They didn’t find it easy: translations of Ukrainian literature were few and far between; there were few familiar names to call on. Why exactly was the literature of one of Europe’s largest countries so unfamiliar? Ukrainian literature is, after all, pretty much as old as any other in Europe – it has its medieval texts, its impressive baroque tradition; its Romantics fit the broader European nationalist patterns; it has its realists and its avant-garde, its modernists and postmodernists. And yet it has barely penetrated the broader world literary consciousness. Well, the reason is simple: Russia.

Systemic suppression of Ukraine's literature

Ukraine has been a prized colonial possession for Moscow since at least the 17th century. The country has plentiful natural resources, most notably its fertile black earth, so vital for feeding an empire whose core is a colder, more barren northern landscape, but also its coal; Ukraine is a land bridge to Europe and the Black Sea – it can be a staging post for waging war but also, via Odesa, a key trading corridor; finally, Ukraine holds the spiritual roots of eastern Orthodoxy – Prince Volodymyr was baptised in Crimea in 988 and spread Christianity throughout the region from Kyiv. The modern Russian state, whose origins come centuries after Volodymyr’s time and are relatively loosely connected with Kyiv, has spent centuries appropriating this history in the service of its civilizational self-image.

Russia has had an obsession with controlling Ukraine and an obsessive fear of losing it

These multiple motivations, which speak to the economic, political and cultural foundations of Russian imperialism, have led to an obsession with controlling Ukraine and an obsessive fear of losing it. This fear is augmented by the character of Ukraine itself: Ukraine is not a passive territory, but a land inhabited by enterprising, rebellious people who, for centuries, have frustrated Moscow’s attempts to subdue them. From the rebellions of the 18th century against Peter I to the Maidan protests against Russian interference of the early 21st, Ukrainians have repeatedly not only fought for their own freedom, but threatened to spread their freedom-loving spirit to Russia itself. The combination of imperial ambition and fear has inspired brutal responses, from Peter’s massacres of Ukrainian towns to Stalin’s artificial famine of the 1930s and Putin’s ongoing genocidal war.

Russia’s colonial violence has not only been physical. It has also been cultural. The Moscow church was already banning religious books in Ukrainian in the 17th century, a practice extended by Peter I in the 18th; in 1847, Tsar Nicholas I sent Ukraine’s national poet, the fiery anti-imperialist Taras Shevchenko, into ten years of arduous military exile and banned him from writing; in the late 19th century, Alexander II introduced legislation prohibiting Ukrainian from almost all spheres of written and educational activity; in the 1930s, Stalin, spooked by the revival of Ukrainian culture in the 1920s, had most of Soviet Ukraine’s writers shot. Vasyl Stus, the brilliant poet who died in the Gulag in 1985, has often been thought of as the last victim of this grim tradition, but such assessments proved hasty. After 2014, writers once again found themselves targets: the journalist Stanislav Aseyev was imprisoned and tortured for three years by Russia’s proxies in Donetsk; the writer and film director Oleg Sentsov was arrested and tortured in 2014 for opposing the occupation of Crimea and imprisoned for five years (both men are now fighting on the frontline against Russia). After 2022, the brutality accelerated: Viktoria Amelina, a novelist and war crimes investigator, was killed in a Russian airstrike in 2023; the children’s writer and poet Volodymyr Vakulenko was executed by the Russians after his hometown was occupied in 2022; the poet Maksym Kryvtsov was killed on the front in 2024.

Given this history, it is easy to see why Ukrainian literature has struggled to gain a foothold on the world literary landscape. Its most talented writers have been imprisoned or murdered, their works confiscated, censored, destroyed. While Russian literature has been widely translated, supported by the powerful resources of the Russian state in its various guises, Ukrainian literature has been suppressed by that same state – translation from and into Ukrainian has been carefully policed, at times banned entirely, by Tsarist or Soviet authorities.

War as a catalyst for change

The absence of Ukrainian literature in the world is not purely a matter of Russian suppression, however: western audiences have often acquiesced with the Russian view of the literatures Russia has supressed, seeing them as mere folkloric curiosities on the fringes of ‘Great Russian Literature’. Scholars, publishers, translators, and the literary press have shown little interest in exploring these cultures on their own terms.

War, however, is a great catalyst for change – it jolts us into action and deeper reflection. It also garners the attention and curiosity of readers, which can translate into book sales. Translators of Ukrainian literature have been busy over the last two years, supported by a growing community of agents, editors and journalists who have taken up the Ukrainian cause. In the worst of circumstances, Ukrainian literature is finally enjoying some recognition.

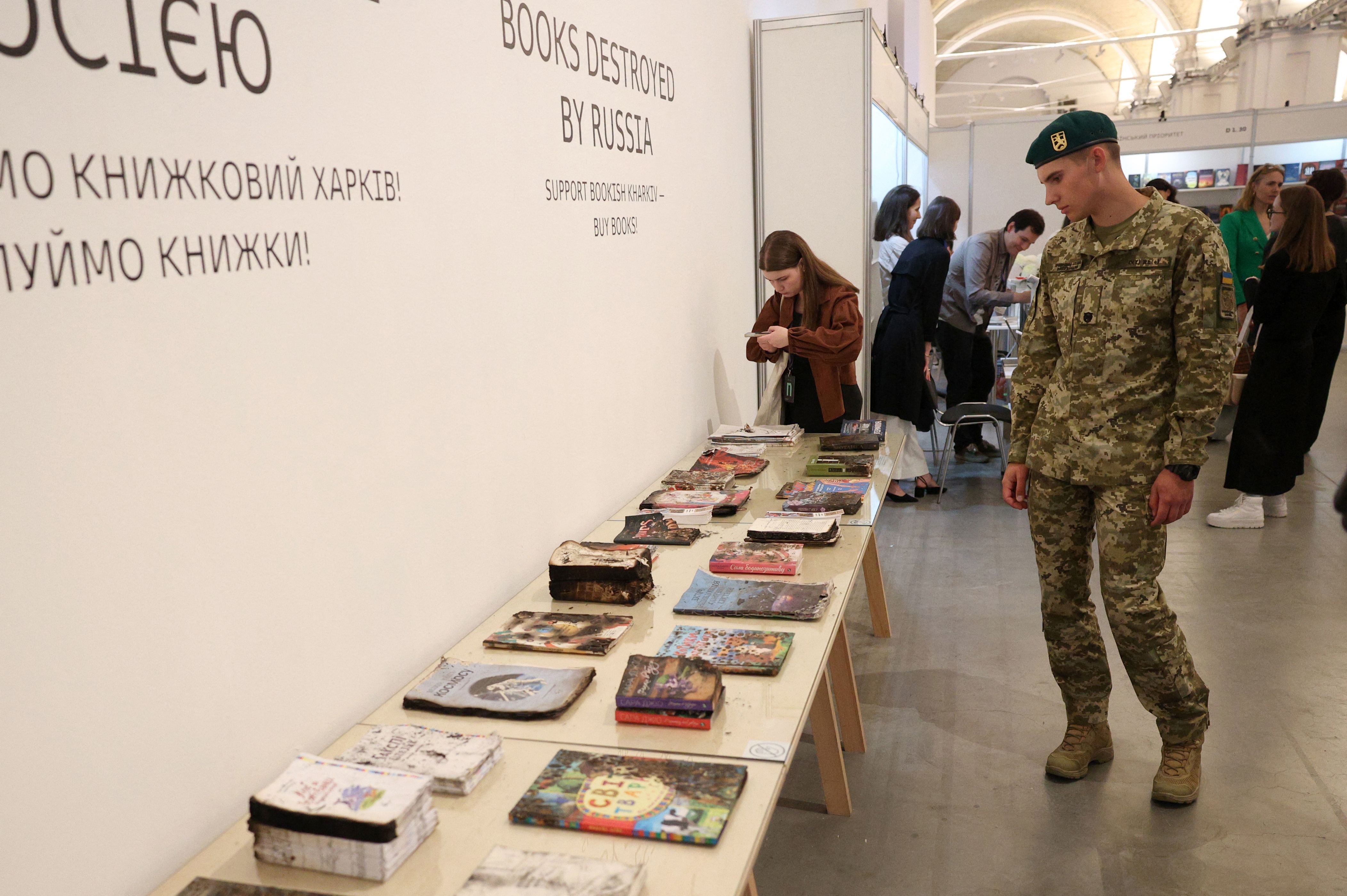

A Ukrainian serviceman stands next to a stand with damaged books of the Kharkiv publishing house, which was destroyed by Russian shelling last month. Photo: Anatolii Stepanov | ANP | AFP

A Ukrainian serviceman stands next to a stand with damaged books of the Kharkiv publishing house, which was destroyed by Russian shelling last month. Photo: Anatolii Stepanov | ANP | AFP

Demand has, naturally, focused on literature about the war. The most recent high-profile book to emerge in this regard is Oleksandr Mykhed’s account of the 2022 invasion, The Language of War (Allen Lane, 2024, transl. Maryna Gibson, Hanna Leliv, Abby Devar). As the title suggests, this is not just a factual account, but a meditation on the experience of war and the struggles we face finding the words to express that experience. It is the latest example of a wave of non-fiction writing that has emerged in Ukraine since 2014. Stanislav Aseyev’s The Torture Camp on Paradise Street (transl. Zenia Tompkins and Nina Murray) and In Isolation (transl. Lidia Wolansky; both Harvard) are acute philosophical and psychological studies of terror and incarceration that are worthy continuations of the 20th century tradition of writing on the Nazi and Soviet camps. A title to watch out for in this regard is Victoria Amelina’s Looking at Women Looking at War (Harper Collins, forthcoming 2025): previously a prose writer, Amelina found that she could only process the war through non-fiction (based on her interviews with women who had experienced Russian occupation) and poetry (some of her war poems appear in the book). Another author who is alive to women’s experience of war is Olesya Khromeychuk. Her The Death of a Soldier Told by his Sister (Monoray, 2022, written in English and available in a Dutch translation by Wybrand Scheffer, published by Atlas Contact) is a memoir about the death of her brother on the frontline in 2017, but also an exploration of the overlapping of grief, rage, and love that war brings. A good example of the growing body of literature written by soldiers is Artem Chekh’s memoir of his (ongoing) military service Absolute Zero (Glagoslav, 2020, transl. Oksana Lutsyshyna and Olena Jennings), a nuanced, non-heroic account of the reality of the trenches.

Alongside non-fiction, other genres are also flourishing, notably novels set in, and written by writers from, eastern Ukraine, the region most affected by the war. Serhii Zhadan’s The Orphanage (Yale, 2021, transl. Reilly Costigan-Humes, Isaak Stackhouse Wheeler; also available in a Dutch translation by Roman Nesterenco with De Geus) is one of the defining works on the pre-2022 war: it is a tense real-time journey through a city split in two by the 2014 invasion. Like Zhadan’s works, Olena Stiazhkina’s Cecil the Lion Had to Die (Harvard, 2024, transl. Dominique Hoffman) studies both the war and the peculiarities of eastern Ukraine, in this case Stiazhkina’s native Donetsk, with humour and insight. The same city is described by Volodymyr Rafeyenko in his The Length of Days (Harvard, 2023, transl. Sibelan Forester) – part sci-fi, part love song to the occupied city. Rafeyenko followed this up with Mondegreen (Harvard 2022, transl. Mark Andryczyk), a novel about the trauma of displacement faced by so many eastern Ukrainians in 2014, and by so many refugees from across Ukraine since 2022. Another notable study of eastern and southern Ukraine, albeit not by a native of these regions, is Andrei Kurkov’s Grey Bees (Maclehose, 2021; transl. Boris Dralyuk), a typically whimsical and tender exploration of Donbas and Crimea.

Flourishing poetry and neglected classics

Perhaps the genre that has flourished most since 2022 has been poetry. Ukrainian poets have responded in real time to the war, often reaching their audiences directly through social media. Notable works in English include Oksana Maksymchuk’s Still City (Carcanet, 2024, originally in English), Halyna Kruk’s A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails (Arrowsmith, 2024, transl. Amelia Glaser and Yulia Ilchuk), Liuba Yakymchuk’s Apricots of Donbas (Lost Horse Press, 2021, transl. Oksana Maksymchuk, Max Rosochinsky, Svetlana Lavochkina) and Serhiy Zhadan’s How Fire Descends (Yale, 2024, transl. Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps). Two publishers mentioned above – Arrowsmith and Lost Horse Press – have an impressive array of contemporary Ukrainian poets on their books that are too numerous to list here. For an overview of how Ukrainian poets responded to the war post-2014, the excellent anthology Words for War (Academic Studies Press, 2017) edited by Maksymchuk and Rosochinsky and featuring several of the names mentioned above, is a must-have.

Contemporary Ukrainian literature is, of course, much more than a response to war, and there are numerous works in translation that reflect its breadth. Oksana Zabuzhko’s Field Work in Ukrainian Sex (Amazon Crossing, 2011, transl. Halyna Hryn) was a seminal feminist work for a generation of Ukrainian women when originally published in 1996, and it remains as urgent as ever. Her epic historical novel Museum of Abandoned Secrets and her wickedly ironic short prose Your Ad Could Go Here are also available with the same publisher in translations by Nina Murray and others. Another important figure in the 1990s/2000s was Yuri Andrukhovych; several of his novels, as well as some of his superb essays, are available in English, though perhaps the best is The Moscoviad (Spuyten Duvil, 2008, transl. Vitaly Chernetsky), a fiendishly funny riposte against Russian imperialism. The botanist-philosopher Taras Prokhasko, who, like Andrukhovych, comes from the western city of Ivano-Frankivksk and was a staple of Ukrainian postmodernism, is another whose works have found new life in translation (the anthology Earth Gods, forthcoming with Harvard, includes my own translation of his magical-realist reimagining of the Carpathians The Unsimple, as well as translations by Ali Kinsella and Mark Andryczyk). Of more recent novels, Tanja Maliartschuk’s layered reflection on memory, history and Ukraine’s links to Central Europe via its Habsburg heritage Forgottenness (WH Norton, 2024, transl. Zenia Tompkins) is a standout, while Oksana Lutsyshyna’s expansive Ivan and Phoebe (Deep Vellum, 2023, transl. Nina Murray) provides fascinating insight into the political turmoil of the early years of Ukrainian independence. There are also some exciting works in the pipeline: Sofia Andrukhvych’s epic Amadoka, which spans the current war, World War II, and Stalinist terror, is being translated by Daisy Gibbons and is scheduled for publication with Simon and Schuster.

Ukrainian classics have been virtually unavailable to English-speaking audiences

The final piece in the puzzle is the most neglected one: classics. Ukrainian classics have been virtually unavailable to English-speaking audiences, often only available in obscure editions in university libraries. English-language publishers specialising in world classics have largely ignored Ukrainian literature. The Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute has sought to rectify this situation with its Library of Ukrainian Literature project, producing translations of writers like Lesia Ukrainka. One of the most fascinating and eternally relevant figures in Ukrainian literary history, Ukrainka’s dramas reimagining western cultures' foundational myths through a feminist, anti-imperialist lens are among the great neglected works of European literature (her Cassandra, transl. Nina Murray, is out later this year). Other highlights include novels of the 1920s renaissance such as Valerian Pidmohylnyi’s psychological exploration of urban life in the early-Soviet Kyiv, The City (transl. Maxim Tarnawsky) and Mike Yohansen’s gloriously eccentric avant-garde ‘landscape novel’ The Learned Dr Leonardo’s Journey with his Future Lover, the Beautiful Alceste, to the Switzerland of the Steppes (in my own translation). Other places to look for Ukrainian classics are Glagoslav Press (the modernist poets Pavlo Tychyna, Maksym Rylskyi, Bohdan Ihor Antonych and others) and Academic Studies Press (who published a pioneering volume of translations of the avant-garde poet Mykola Bazhan). For Ukrainian classics and more online, a great place to turn is the London Ukrainian Review, published by Ukrainian Institute London, which features, for example, a whole issue on Lesia Ukrainka.

Ukraine's place in the family of literatures

Progress has been made, then. The challenge now is to capitalise on this momentum and ensure that Ukrainian literature is recognised not only for its astounding war literature, but for the whole breadth of its richness. This will require publishers to overcome the attention span problem as focus shifts to other global events. It will also require institutional and financial support – grants like those provided by the Ukrainian Book Institute, House of Europe, or local equivalents in countries around the world, will continue to be crucial. Ukrainian literature has been denied its place in the family of European and world literatures for too long; by the same token, readers around the world have also been denied its riches and its insights. These insights that could have been in crucial in foreseeing and understanding the current war, but they are also relevant wherever culture thrives under pressure and freedom stands up to tyranny.

Uilleam Blacker (1980) is associate professor at UCL and a literary translator, specializing in Ukrainian and Eastern European culture. He writes about cultural memory, cities and Ukrainian literary heritage. The Atlantic, The Guardian and The Times Literary Supplement, among others, published his articles. His translations have been published by Deep Vellum and Harvard University Press, and appeared in numerous anthologies and journals.

This article was published in collaboration with The Dutch Review of Books, who published the Dutch translation.