Chief of Russia's Security Council Nikolay Patrushev is the person closest to Putin, and the most sinister figure in Russia's political elite. His views appear to be a seething brew of anti-Western conspiracy theory, paranoia and traditional statism. For him everyone is equally cynical, and talk of democracy is hollow hypocrisy. In his views everything is war and he even favours a return to a sort of 'war communism'. Our columnist Mark Galeotti considers him 'the most dangerous man in Russia'.

Nikolay Patrushev (picture Russian Embassy in Germany)

Nikolay Patrushev (picture Russian Embassy in Germany)

Suddenly, it seems that you can hardly open a Russian news site without hearing what Nikolai Platonovich Patrushev, secretary of the Security Council, thinks about everything from the war in Ukraine to rural healthcare. That this habitually private figure – the greyest of grey cardinals – is suddenly so active in the public sphere is in itself both a worrying and an encouraging sign. As the hawk’s hawk, Patrushev’s new prominence demonstrates how the war is turning Russia into a barracks state, in which everything can and often is being securitised. Yet the fact that he is actually having to argue his case demonstrates that there is still resistance within the apparatus of the state to his dangerous brand of creeping totalitarianism.

The power of influence

Patrushev is a man with huge authority but no constitutional power. The Security Council (SovBez) itself is an essentially consultative body, a place for the key security-related officials can meet to discuss policy and brief the president. It has no power as such. Both in the constitution and, as was made painfully clear in the infamous televised session before the invasion of Ukraine, in practice, the tsar decides and the boyars obey. This is no modern Politburo.

However, Patrushev (like, one might add, Stalin back in the 1920s) has understood and exploited the power of bureaucracy. The SovBez is serviced by a secretariat that, while technically part of the wider Presidential Administration, is effectively autonomous. Once, this was little more than a small team of functionaries circulating agendas and making sure there were pencils and paper at every seat before meetings, a body used as much as anything else as a hostel for ageing spooks and generals on their way to retirement.

Since Patrushev swapped the role of director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) for Secretary of the SovBez in 2008, making him the longest-serving incumbent of that position yet, he has transformed the secretariat. It has grown, recruiting not superannuated siloviki but ambitious youngsters and specialists, supplementing them with serving spooks and soldiers seconded to the agency. More to the point, most security-related materials that end up on the president’s desk have been drafter, edited or at least approved by the secretariat.

In the process, the quiet yet forceful Patrushev has become in effect Putin’s national security adviser. He is not the only person who gets to frame the president’s view of the outside world – not least, because the various intelligence services jealously defend their right to brief him directly – but he is arguably the single most important one.

The hawks’ hawk

As such, he has been at the centre of all key security decisions for years, and has demonstrated himself to be the hawk’s hawk, genuinely convinced that Moscow faces an existential political threat from a hostile West engaged in a long-term, covert political war against Russia. Indeed, he has openly stated his view that the United States ‘would much prefer that Russia did not exist at all, as a state.’

He was convinced that the 2013-14 Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine was little more than a CIA plot, and strongly endorsed the annexation of Crimea. He has been accused of having been the backer behind the abortive 2016 coup in Montenegro, aimed at trying to prevent it from joining NATO. He publicly accused opposition leader Alexei Navalny of being a Western catspaw. Now, he appears fervently committed to the war in Ukraine.

On 21 February Putin's elite supported the recognition of the People's Republics in the Donbas. 3 days later the invasion started (picture Kremlin)

On 21 February Putin's elite supported the recognition of the People's Republics in the Donbas. 3 days later the invasion started (picture Kremlin)

His views appear to be a seething brew of conspiracy theory, paranoia and traditional statism. In a recent interview in Argumenty i Fakty, he claimed:

‘The style of the Anglo-Saxons has not changed for centuries. And so today they continue to dictate their terms to the world, boorishly trampling on states’ sovereign rights. Covering their actions with words about the struggle for human rights, freedom and democracy, they are actually implementing the doctrine of the “golden billion,” which suggests that a limited number of people can flourish in this world. The destiny of the rest, as they believe, is to bend their backs in the name of their goal.’

In one paragraph, he encapsulates so much of his world view. A sense of civilisational struggle, that Russia is engaged in a struggle with ‘the Anglo-Saxons’ not over specific policy, but as part of a multi-generational political-cultural battle, in which, he claimed in April, ‘America has long divided the whole world into vassals and enemies.’

A wilful blend of self-deception and self-justification, whereby the invasion of an independent nation is ignored while he lambasts the West’s supposed ‘boorish trampling on states’ sovereign rights'. (At the end of May, while Russian troops were shelling Ukraine, he claimed that ‘we are for Ukraine to remain sovereign, to preserve its territorial integrity’ but ‘a number of states are already actively working to dismember it,’ and ‘Poland is apparently already moving to seize western Ukrainian territories.)

An unthinking assumption that rhetoric is necessarily empty, that everyone is equally cynical, and talk of democracy is hollow hypocrisy.

A reliance on a conspiratorial and almost mystical view of the world – it is worth remembering that Patrushev’s claim about the US desire to dismember the Russian Federation is based on a Russian psychic’s claims to have read former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s dreams and back in August he warned that ‘behind-the-scenes conspiracies… often decide the fate of sovereign states’ – that in this case manifests itself in the fantasy of the ‘golden billion', the idea that there is a secret and deliberate plan to allow an elite to prosper at the expense of everyone else.

The believer

The problem is this: Patrushev is neither a fool nor a charlatan. He is intelligent, committed and hard-working, able quickly to master a complex brief. Unlike so many ex-Soviet bosses, he does not bully his underlings to make himself feel like a big man, but instead is known for his manners and his capacity to listen. Despite the kind of allegations that swirl around every senior Russian figure, he does not even appear to be especially corrupt, although arguably the careers and fortunes of his sons Dmitri (who became a banker, then Minister of Agriculture) and Andrei (now big in the energy industry) are not entirely down to their own efforts.

Yet this figure, who certainly seems closer than Putin to their shared idol, ascetic KGB chief turned General Secretary Yuri Andropov, nonetheless has played a crucial role in pushing Russia down this current disastrous road to war, confrontation and immiseration. Furthermore, he seems to believe that the answer is not to recalculate but rather to double down.

He is one of the key advocates of the new narrative, so central to Putin’s 9 May speech, that the war in Ukraine is actually a war with NATO. Furthermore, he is smart enough to recognise that this struggle will be a long and difficult one, but amnesiac enough to seem to believe that the answer is to try and replicate the planned, state-controlled economy of the Soviet era.

On June 5 Russia again attacked Kyiv

On June 5 Russia again attacked Kyiv

He would not frame it in those terms, he might not even think that is what he doing, but the logic of the hard-liners’ manifesto, of what he described to Rossiiskaya Gazeta as a ‘deep structural restructuring of the Russian economy’ is not only one in which the state increasingly intrudes into the market, but in which the SovBez and its busy secretariat plays a growing role, effectively supplanting Prime Minister Mishustin’s cabinet.

Indeed, according to Kommersant, he has already told a meeting of the SovBez Scientific Council that he wants ‘a single strategic plan for the transition to structural modernisation of the internal contours of the national economy.’ If his words back in April are anything to go by, this means a plan not shaped by ‘the fascination of our entrepreneurs… with market mechanisms alone’ but instead driven by the state and, if needs be, ‘significantly tighter discipline.’

What is interesting is that the hawks had pushed this line right at the start of the war, and for a day or two it looked as if they would carry the day and what might be considered ‘War Communism’ without the pretence of communism might be imposed. The technocrats fought back and Mishustin, his cabinet, and Central Bank chair Elvira Nabiullina were, at least provisionally, given control over the economic response which Putin himself continued to focus on the war and play with his soldiers.

That may not last forever, not least as there are limits to what can be done with fancy financial footwork. Russia’s balance of payments surplus may be looking healthy, but if there is little on which this money can be spent, then it is pretty moot. Patrushev may well be smelling blood, or at least trying to position himself for a renewed push to have the economy securitised.

Everything is war

After all, for him, everything is warfighting. Not just domestic politics and foreign relations but everything. The economy is not just the engine of war but a battlefield in its own right, where ‘Western countries seek to provoke a full-scale economic crisis in Russia, which carries the threat of exacerbating the social situation in the country'. Education ought to be about defending national values and morale: ‘in the conditions of the hybrid war, which is now deployed against Russia… teachers are at the front line.’ As for rural healthcare, it was part of an agenda he laid out in Kazan for ‘the neutralisation of threats to national security in the implementation of state policy in the field of demography and improving the quality of life of the population of rural areas’ not least as this was crucial for food security.

There have been many understandable but politically-illiterate attempts to brand Putin’s Russia as fascist. However, the irony is that Patrushev, one of the only senior Russian figures still leaning heavily on the ‘de-Nazification of Ukraine’ line that even Putin is largely eschewing now, would probably recognise and approve Mussolini’s totalitarian motto: tutto nello Stato, niente al di fuori dello Stato, nulla contro lo Stato, everything in the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.

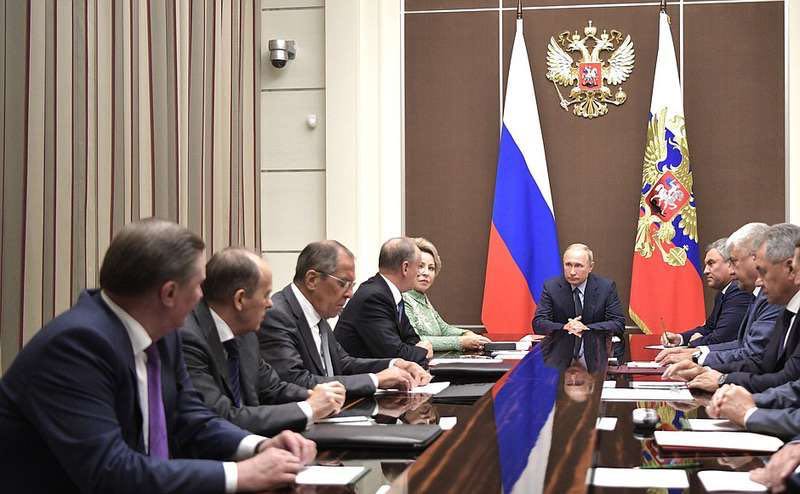

Putin with his Security Council (picture Kremlin)

Putin with his Security Council (picture Kremlin)

And this is the man standing by the side of the president. Tabloid suggestions that he may actually be a potential successor or stand-in have little plausibility – this would be both constitutionally impossible and politically dangerous, not least because of the harm it would do the chain of command. Besides, he has never sought direct political power but prefers influence behind the scenes: he is a Cardinal Richelieu, not a Bismarck.

But the man who approvingly name-checks the tsarist General Mikhail Skobelev, who oversaw the 1881 massacre of Geok-Tepe in Turkmenistan and believed that ‘the duration of the peace is in direct proportion to the slaughter you inflict upon the enemy. The harder you hit them, the longer they remain quiet,’ who believes Russian psychics have proven a dark conspiracy against Russia, and who feels that the interests of the state are best served by resuscitating the worst of the Soviet system, without the idealism that in theory at least justified it – this is the man who whispers in Putin’s ear and shapes his view of the world. Which is why I continue to call him ‘the Most Dangerous Man in Russia.’