Thousands of Ukrainians are trapped in Russian 'temporary detention centers' awaiting deportation to Ukraine. Among them are long-term Russian residents and civilians from occupied territories, many held in deplorable conditions and subjected to torture. Independent Russian journalist Anna Snegireva reports how they remain trapped in Russia, often alongside prisoners of war, as deportation to Ukraine is currently impossible.

Screengrab of a video from the Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs, which agreed to deport 65 Ukrainians back to Ukraine. They had been stuck in no-man's land at the Russia-Georgia border for two months after being expelled from Russia. Source: X

Screengrab of a video from the Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs, which agreed to deport 65 Ukrainians back to Ukraine. They had been stuck in no-man's land at the Russia-Georgia border for two months after being expelled from Russia. Source: X

Russia is not only detaining Ukrainian prisoners of war, but also thousands of civilians. Mykhailo Savva, a political scientist from the Ukrainian NGO Center for Civil Liberties, estimates that around 16,000 civilians have been deprived of their liberty since the start of the full-scale invasion. These include residents of occupied Ukrainian territories abducted from their homes and later taken to Russia.

They are scattered across at least 189 official detention sites – prisons, penal colonies, pre-trial centers, and deportation facilities – while many more are held in unofficial places like basements or FSB ‘temporary’ cells.

The Ukrainians held in Russia fall into two main groups. The first are Ukrainian prisoners of war (POWs), who have been captured as enemy combatants. The second group includes Ukrainians who are deemed to be in Russia illegally. Many of them have served prison sentences, either in Russia or in the Ukrainian territories which Russia occupies. The second group has been earmarked for deportation, but since deportation to Ukraine is impossible detention stretches into months or years. Although not combatants, they are nonetheless held alongside Ukranian prisoners of war in Russian prison facilities.

Deportation facilities

The plight of deported Ukrainians first reached broad public attention in summer 2025, when dozens of citizens expelled by Russia were stranded at the Verkhniy Lars crossing on the Russia–Georgia border. Georgia refused them entry, and Russia would not take them back. These people spent weeks in a basement in no-man’s land, trapped in legal and physical limbo. To protest, some launched hunger strikes, others harmed themselves; Novaya Gazeta Europe reported that one man attempted to cut his throat in desperation.

This was not an isolated crisis. Human rights defenders say that around 800 Ukrainians are currently held in TsVSIG facilities across Russia. Officially, TsVSIG are ‘temporary detention centres for foreign nationals’ awaiting deportation. In practice, deportation to Ukraine is impossible due to the ongoing war, and no third country has agreed to accept these people. As a result, temporary administrative detention has become indefinite imprisonment for this group.

Inside of the TsVSIG facilities, conditions are more like prisons than 'temporary accommodation’. In the Smolensk TsVSIG, detainees reported that 87 people were held together. About thirty of them have families in Russia, and do not want to return to Ukraine. ‘Here is my cabin’, one man told me, showing a video of his cell: four men sleeping on bunkbeds, crammed into a small room, clothes and towels hung on the beds. They were ‘always inside, always being watched. We get a forty minute walk each day. They check every morning if the old man in our cell is still alive,’ says the man in a video published by ASTRA.

Deportation center in Smolensk region, ASTRA.

Deportation center in Smolensk region, ASTRA.

Deplorable conditions

Other accounts confirm the same picture. I documented a case of a Ukrainian mother, who was held with her two children in one of these centers for more than a year. Her children have not attended school for a second year in a row. She fears speaking out, knowing that the authorities might transfer the children to state custody.

Inmates describe severe deprivation of basic supplies. One detainee said he receives razors only under guard. After ASTRA’s first report, conditions improved slightly: detainees were issued hygiene kits, bedding began to be changed twice a month, fire alarms were installed in cells, and inmates received at least half a roll of toilet paper per person and soap.

Some of the most disturbing testimonies involve medical neglect and unsafe cell placements. People with HIV and tuberculosis are held without adequate treatment. Others share cells with mentally ill detainees, and are expected to ‘watch over’ these people without training. ‘I am not a nurse,’ a Ukrainian ex-prisoner who served a term in Russian prison told me. ‘But they locked me in with a sick person and told me to cope.’

‘We sit here like dogs in a cage,’ detainees say. ‘If we protest, they will bring OMON [riot police], beat us, and call us extremists. There is no point.’

Many of them fear violence, both inside the centre and if they are returned to Ukraine, where military conscription awaits: those Ukrainians who eventually returned home from the Verkhniy Lars ‘no-man’s land’ were taken directly to military enlistment offices upon their arrival.

Tools of coercion

Human rights defenders stress that TsVSIG detention centers have become tools of coercion. Several detainees told ASTRA that officials openly said they were being kept as a ‘reserve’ for future prisoner of war exchanges between Russia and Ukraine. According to Dmytry Gurin, senior legal advisor at the European Prison Litigation Network, senior lawyer at the Memorial Human Rights Centre, and an expert to the Council of Europe, civilians were sometimes added to prisoner-of-war swap lists at the last moment, without explanation.

‘At some point, they decide it is more useful to keep them this way. Exchanges go on, and sometimes, in groups that were supposed to consist of military prisoners, former civilian detainees were simply added in,’ Gurin said in a comment for RAAM.

Ukrainians are detained for months or years without clear prospects. Many of them previously lived in Russia for decades, working legally, paying taxes, and raising children with Russian citizens. Some sought to formalize their status under migration amnesties, only to be arrested later. The war turned them into outcasts overnight.

As one man explained from inside a detention center: ‘They destroyed our families. If they send me back, they will force me to fight. Against my own son, who is now in the Russian army.’ Others, after finishing prison sentences in Russia, were transferred straight to TsVSIG.

'If they send me back, they will force me to fight. Against my own son, who is now in the Russian army’

One detainee, born in Russia in 1980 and raised in Ukraine, spent decades moving between the two countries. In 2007, after hearing President Vladimir Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, he decided to return to Russia for good. He tried repeatedly to obtain Russian citizenship — through consulates, the resettlement programme for compatriots, and local migration offices — but was consistently refused. He built a family in the Volgograd region, lived there legally, and raised children.

In 2023, after he criticised the local authorities for failing to maintain local pavements and attempted to organise a small protest by disabled residents, he was arrested. His residence permit was annulled while he was serving nine days of administrative detention, and he was transferred to a deportation centre. After more than a year in custody he has lost his family, fallen into debt and exhaustion, and now says he wants to be deported simply so that the ordeal can end — even if it means being sent to a country with which he has no ties and risks conscription. ‘They just want to let me rot in prison,’ he said.

Another man, who had lived and worked in Russia for years, was attacked and stabbed in a dispute over the so-called ‘special military operation’ after February 2022. While his attacker received a prison sentence, he himself was placed in a TsVSIG-facility and has remained there for years. ‘When I came out of intensive care, prosecutors and migration officers were already waiting for me,’ he told ASTRA. Officials decided he was in Russia illegally and ordered his deportation. He was never compensated for the attack and instead found himself confined in a cell with dozens of others, including elderly and sick detainees.

Gurin explained that deportees could not be deported to Ukraine through the border with the EU because their names appeared in the Schengen Information System (a database used by European states to flag individuals for refusal of entry) at Ukraine’s request. In practice, this meant that Ukrainians who had served prison sentences in Russia were turned back at the Estonian or Latvian borders and returned to Russia. Georgia has also refused entry to these people. Ukraine had offered direct deportations at the border or via Belarus, but Minsk refused to allow the transfers and Moscow did nothing to press its ally. ‘As a result, people remain locked up for months and years,’ says Mykhailo Savva in a comment for RAAM.

Deported Ukrainians at the Georgian border, Source: Anna Skripka, Facebook

Deported Ukrainians at the Georgian border, Source: Anna Skripka, Facebook

Civilians kidnapped and held alongside POWs

Unlike deportation centres, where Ukrainians are trapped in a bureaucratic dead end, another group of civilians is held much deeper inside Russia — in the same system as prisoners of war. Human rights defenders estimate their numbers to be in the tens of thousands.

Mykhailo Savva told RAAM that at least 16,000 civilians have been detained by Russia since 2022. ‘For Russia, all Ukrainians are potential rebels against the so-called “special military operation”. That is why they do not distinguish between soldiers and civilians: they take everyone. People are kidnapped from their homes, from the streets, from workplaces. Some are charged with espionage or terrorism, but many are not charged at all — they are simply held.’

16,000 civilians have been detained by Russia since 2022

One of them is Dmytro Khilyuk, a Ukrainian journalist for the news agency UNIAN. He was kidnapped by Russian troops in March 2022 from a house requisitioned by the Russian military in Kyiv region, where he was staying with his father. Both men were detained, but while his father was released a few days later, Dmytro disappeared into the Russian detention system for more than three years. After weeks in improvised basement prisons in occupied villages, he was moved through Belarus into Russia, and later shuffled between detention centres and penal colonies. In August 2025, Khilyuk was finally released as part of a prisoner exchange.

Speaking exclusively to RAAM, Khilyuk described how civilians like him were treated as if they were POWs: ‘Even civilians like us were given POW status. Back in Hostomel [a town near Kyiv] they made prisoner-of-war cards for all of us. I remember being photographed, and there were forms to fill in — whether you had any injuries, how severe they were, if you were recovering or in critical condition. These were cards designed for soldiers, but they issued them to civilians.’

Khilyuk recalled that while still held in Russian-occupied territory, he and others were locked in industrial refrigerators repurposed as prison cells. ‘We were all hostages. This is a terrorist tactic — to kidnap civilians and keep them without charges, just to hold them for exchange,’ he said in an interview for RAAM.

Dmitro’s release from Russian captivity. Source: X

Dmitro’s release from Russian captivity. Source: X

Torture

Research by the Ukrainian human rights group ZMINA confirms that Khilyuk’s treatment is not one-off. Their 2025 report shows that arbitrary detention and enforced disappearances in occupied territories are part of a systematic state policy. Testimonies consistently identified the FSB as the main agency responsible for abductions and torture, coordinating repression across the occupied regions. Some detainees are placed under fabricated criminal charges such as ‘espionage’ or ‘terrorism’, while many others are held without any charges at all, in complete legal limbo. ZMINA concludes that these widespread practices amount to crimes against humanity.

For families, the result is endless uncertainty: loved ones vanish into the Russian prison system, without charges, without contact, sometimes for years. ‘Those arbitrarily deprived of liberty, kept incommunicado — there is absolutely no contact with them, no one is allowed access’, says Savva.

'When I was first allowed to write to my family, I was given only two lines'

‘When I was first allowed to write to my family, I was given only two lines. I did not know where I was, what would happen to me, or whether they even knew I was alive,’ Khilyuk said.

He also reported that civilians were subjected to beatings — he himself was beaten multiple times while in detention. These physical abuses were accompanied by psychological torture and a total informational vacuum, leaving him unsure of his fate for long periods.

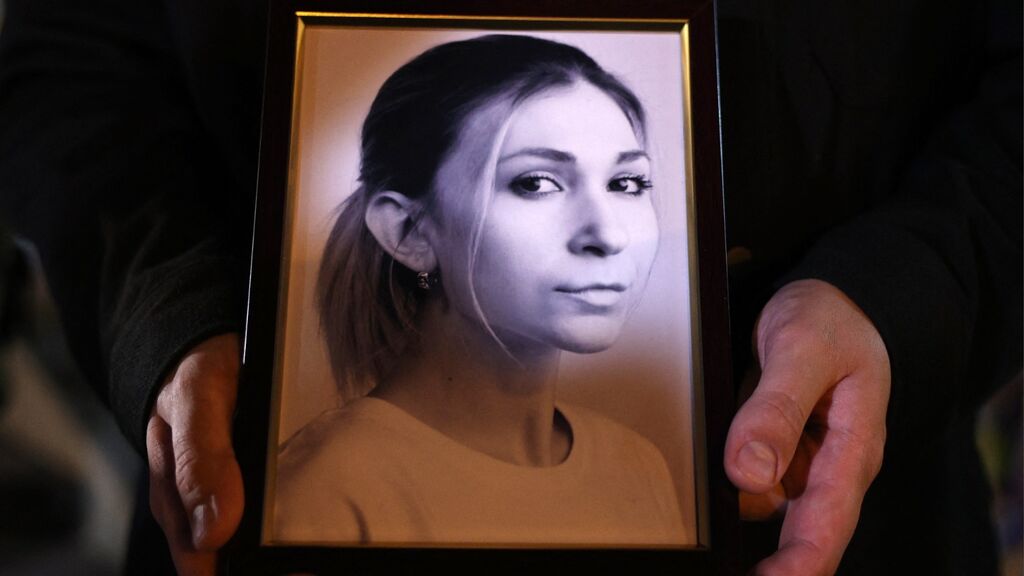

One of the best-known and grimmest examples of this systematic torture is the case of the 27-year old Ukrainian investigative journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna. Captured in the summer of 2023 in Russian-occupied territory while reporting on detention centers, she was held without charge and without access to a lawyer. A forensic medical examination of her body — returned to Ukraine in February 2025 — showed signs of torture and ill-treatment. Preliminary reports also indicate possible electric shock burns and other injuries consistent with violent abuse.

Portrait of Viktoria Roshchyna at a memorial honoring fallen Ukrainians. Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / AFP / ANP

Portrait of Viktoria Roshchyna at a memorial honoring fallen Ukrainians. Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / AFP / ANP

‘Torture has become routine. Our data shows that the overwhelming majority of detainees are subjected to it. And they suffer not only physical pain but also daily humiliation,’ said Mykhailo Savva of the Center for Civil Liberties.

His warning is echoed internationally. In her annual report to the UN Human Rights Council, Special Rapporteur Mariana Katzarova described ‘the continuing widespread and systematic recourse to torture and ill-treatment by Russian law enforcement officials, security forces, penitentiary officials and members of the armed forces.’ She pointed to a ‘clear pattern of participation or acquiescence by medical professionals in the most horrific forms of torture, especially against Ukrainian detainees.’

The BBC also reported systematic torture of Ukrainian POWs in the prison camp IK-10 (located in the autonomous republic Mordovia in the west of Russia) and said survivors saw Ukrainian civilians held there as well. Witnesses alleged medical staff were involved in the torturing, with one feldsher using a stun gun on prisoners.

The situation is only worsening. In September 2022 Russia ceased to be a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, and this year the government also announced its exit from the Convention for the Prevention of Torture.

‘Concentration camps are a much less cruel regime’

Human rights defenders say Russia’s treatment of Ukrainian civilians is a blatant breach of the rules of war.

‘Civilians from occupied territories cannot be abducted and held as prisoners of war. The Geneva Conventions forbid this absolutely,’ says Mykhailo Savva. ‘If these were concentration camps, that would actually correspond more closely to the Geneva Conventions. Concentration camps are a much less cruel regime. But Ukrainians are kept under prison conditions in facilities all across Russia; from the western border to the Pacific Ocean.’

According to the Center for Civil Liberties, Ukrainians in Russian custody fall into a second category once formal criminal cases are opened. In these instances, at least some information becomes available, since even state-appointed lawyers create a minimal communication channel. Among this group are both civilians and prisoners of war. Human rights defenders stress that prosecutions of POWs are categorically prohibited under international law, yet Russia has already sentenced at least 300 prisoners of war and roughly the same number of civilians.

Russia has already sentenced at least 300 prisoners of war and roughly the same number of civilians

Human rights defenders say their fate depends not on law, but on fragile diplomatic arrangements and international pressure.

Savva argues that Ukraine and its partners should pursue cases before the International Court of Justice and encourage states to apply universal jurisdiction to prosecute abductions and torture.

So far, the International Committee of the Red Cross has had little access, and Western sanctions have not freed civilians. ‘There are no legal mechanisms today to force Russia to stop these practices or to grant access through courts. Threats and pressure do not work. That leaves only one option — diplomacy. It is imperfect, because Russia refuses normal diplomatic contact. But we see that Middle Eastern countries have acted as mediators in exchanges, and for that we are grateful, because every life saved matters. Legal methods do not work here. What works are diplomats — pleading, negotiating, offering something in return, and pulling people out,’ concluded Dmytry Gurin.

Help ons om RAAM voort te zetten

Met uw giften kunnen wij auteurs betalen, onderzoek doen en kennisplatform RAAM verder uitbouwen tot hét centrum van expertise in Nederland over Rusland, Oekraïne en Belarus.