The big Russian-Belarusian military exercise Zapad-2017 is in full swing. Speculations as to what Russia is up to abound. The Kremlin, bizarre as it sounds, genuinely fears that some day it might face a military challenge from the West, while it is closing its ears to critics of its own conspiratorial world view. But something similar can be said for the West, argues security expert Mark Galeotti for RaamopRusland. So we witness mutual incomprehension exacerbated by the retreat of expertise and a clash of world views. High time for a realistic assessment of our relationship.

Zapad 2017 (pictures Russian ministry of Defense)

Zapad 2017 (pictures Russian ministry of Defense)

The much-discussed joint Russian/Belarusian Zapad-2017 military exercises are in full swing and, at least as of writing, Russia has not mustered 100,000 troops on NATO’s borders, invaded Ukraine or the Baltic States, shown signs of planning to occupy Belarus, or done any of the things that the more alarmist Western reports suggested. Instead, they seem to be precisely what one would expect, a major, regular sequence of training exercises, with a side-order of psychological warfare to exacerbate and exploit European neuroses. Zapad offers a useful window into Russian military thinking and capacities, but it also provides an interesting example of one of the fundamental issues behind the current Russia-West crisis: mutual incomprehension exacerbated by the retreat of expertise and a clash of world views.

Western worries…

In part, the Western hype about Zapad reflects institutional and individual interests. Getting European countries to reach the NATO target of spending 2% of GDP on defence is an uphill struggle, and there is a political imperative to keeping people nervous as a means to this end. For Ukraine, and some frontline European states, there is also an advantage in leveraging a presumed threat from Moscow to attract support and deflect criticism. Then there is also a growing body of self-proclaimed experts eager to capitalise on the crisis of the moment with all kinds of half-understood but fully-bloodcurdling assertions about a mythical 'Gerasimov Doctrine' and a 'new way of war'.

Yet at the same time, it also reflects understandable concerns about a Russian regime that is not only still involved in combat operations on the territory of one of its neighbours, but also maintains a high tempo of intelligence and subversion activities across the West. It is also pouring a considerable proportion of its resources into military modernisation (around 30% of the total federal budget goes to security in its various forms), and its exercises seem to be wargaming aggressive, 'shock and awe' operations. Combine that with the bellicose rhetoric of the Kremlin and its propaganda mouthpieces, such as TV presenter Dmitri Kiselev’s relish at the thought 'Russia is the only country in the world capable of turning the USA into radioactive dust', and suspicions about the Kremlin’s intentions are not conjured from thin air.

…meet Russian paranoias

At the same time, though, the world looks very different through the Kremlin’s windows. Zapad is a wargame of two halves; the latter days are testing how Russian forces would fight a full-scale conventional war with a well-armed enemy – NATO – but the earlier stage was built around the premise that they faced a combination of high-tech long-range attack and close-quarters operations by foreign saboteurs and special forces. Although there is always a degree of theatricality about exercises, for them to be useful and effective, they ought to model as closely as possible the actual kinds of warfare an army thinks it may be called on to fight. To Westerners it may sound bizarre and implausible, but the Kremlin genuinely fears that it might some day face a military challenge not necessarily from the whole NATO alliance, but perhaps from a coalition of some NATO states, and that they would start their aggression by stirring up dissent behind the lines, and sending in commandoes to engage in military-political operations intended to spread chaos and break lines of communication.

After all, it is not simply Kremlin rhetoric that lumps together the 'Arab Spring' risings, the 'colour revolutions' in its post-Soviet neighbourhood, and Ukraine’s 'EuroMaidan' as regime change operations made in the USA. This has become orthodoxy, and I am regularly amazed how many smart, educated Russian military or administration interlocutors appear truly to believe this. This also helps explain Putin’s determination to defend Assad’s regime in Syria, an intervention now marking its second anniversary. In the main it was to distract the West and to force Washington to take Moscow seriously and stop trying diplomatically to isolate it. But it was also to draw a line, to demonstrate that Russia would not allow the Americans to topple yet another of its allies.

Military drills Zapad 2017

Military drills Zapad 2017

This is, of course, wrong. It is every bit as muddled as the Western perception that an article in 2013 by newly-promoted Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov, a career tank commander with no serious track record as a military thinker, somehow represents the blueprint for some radically new and subversive way of war. More than anything else, it represented an attempt to respond to Russian concerns about a perceived Western approach, and to defend the relevance of the armed forces and thus their budgets.

So, both NATO and Russia are desperately trying to work out how best to respond to a perceived new age of war by engineered revolution, each assuming that it is the other who has mastered these dark arts, and that they themselves are trying desperately to catch up. It would almost be darkly funny, where it not so expensive and dangerous.

The understanding gap

During the Cold War, the great worry was the 'missile gap' between superpowers. Now, it is only a matter of time before someone starts talking about an 'information warfare gap', or – even worse – a 'hybrid gap'. But arguably the real resources to worry about are not the relative strengths of missiles, tanks, or even hackers, but a serious and profound gap between Russia and the West in comprehending the other.

In the West, there is a depressing but not unexpected race to the bottom, as policy makers and news media alike pay undue attention to the more extreme, and often least insightful voices in the pundit sphere. As has been said in other fora, a particular problem was the neglect of Russian studies and expertise in both academic and policy institutions through the 1990s and into the 2000s, leading to a shortage of young analytic talent with language skills but also experience living and working in Russia.

At least the real experts and more sober voices do have the opportunity to be heard in the West, though, to join public and policy debates freely. In Russia, the channels of information are far less open, and if anything the Kremlin has been closing its ears to voices questioning its own conspiratorial world view. Just as Putin’s own personal circle of confidants and cohorts appears to have steadily shrunk, with an ever-greater proportion of nationalist KGB veterans and self-interested embezzlers, so too his informational orbit is narrower and narrower. Foreign minister Sergei Lavrov no longer has much of a role; other ministers are likewise confined to a simply executive role, there to enact, not discuss policy. The professional analytic community – from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, through even many of the General Staff’s apparatus, and especially the institutchiki of the think tanks and academe – are increasingly desperate and despondent.

Much of the writings and discussions that we in the West often assume is directed towards us, actually represents conversations within Russia, and attempts to penetrate the iron curtain drawn around the Kremlin. For example, the recent blueprint for a ‘reset’ of US-Russian relations from Fyodor Lukyanov, research director of the Valdai International Discussion Club and Alexei Miller of the European University of St Petersburg, excerpted by Raam op Rusland, is as much as anything a cry of despair as a roadmap. It is a great snapshot into what Russian foreign policy specialists are thinking and saying – but not into what Putin and his cohorts are likely to do. They scarcely pay attention to institutchiki these days, except for those reports commissioned by the Presidential Administration – and whose conclusions are dictated by it, too.

What is to be done?

For the moment, what can be done? First of all, it is worth being honest and accepting that while the Russians’ assumptions about Western hybrid war may be mistaken, there is some small basis for them. There is still a central, unresolved question about Western, or rather US strategy towards Russia. Is it simply to adopt a modern version of 'containment', finding ways to reduce the risks and effects on the West while waiting for this regime to fall and the Russian people to find their way to some more congenial one? Or is it actively to help that process along?

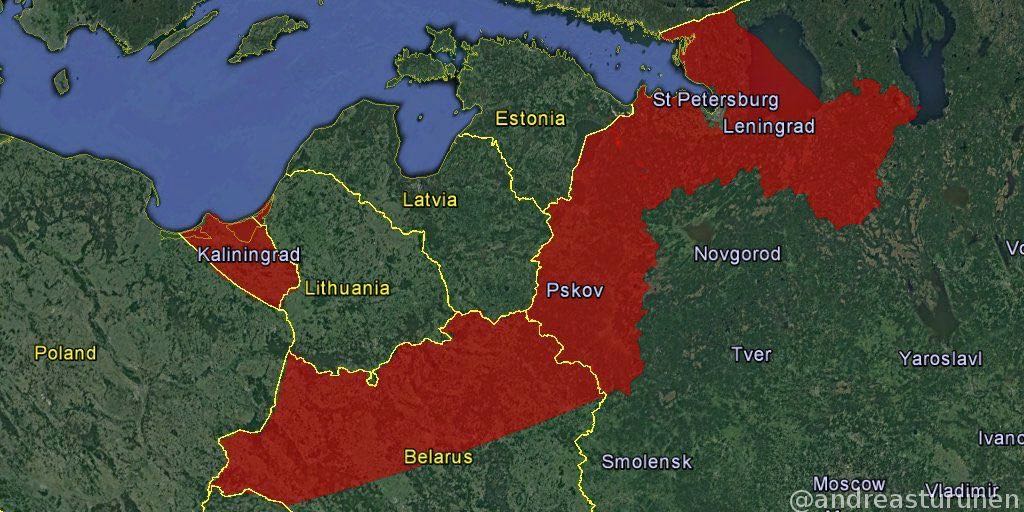

Map of military drills Zapad 2017 in Belarus and Russia

Map of military drills Zapad 2017 in Belarus and Russia

No one will formally admit to the latter, but policy conversations in Washington do often meander that way, and there are activities such as the support for anti-government movements carried out, sometimes covertly, by agencies such as the National Endowment for Democracy, that come close to meeting the Kremlin’s definition of hybrid warfighters. Containment or what George Kennan in 1948 called 'political warfare': either is a valid approach, but at present the policy is neither clearly one nor the other. Or, to put it another way, there is enough talk of political warfare to worry the Kremlin, but not enough to undermine it. If the decision is made to embrace political warfare, so be it, but if not, let there be a clear, explicit and genuine commitment to avoid any such measures.

Secondly, there needs to be a greater appreciation that language matters. Heightened rhetoric and exaggerated claims of the threat may have value as political instruments in the short term, but they have serious longer-term costs. They alarm Moscow, and empower the hawks and nationalists around Putin. They encourage, frankly, bad analysis in the West. They also ironically empower Putin. One of the central elements of his own 'political warfare' campaign against the West – because let there be no mistake, he is waging one – is to make Russia seem so formidable and problematic, that it seems there is no valid alternative to making a deal with him and granting him the kind of status and hegemonic role over Ukraine and the rest of his self-proclaimed 'sphere of privileged interest' that he craves.

Zapad, and the NATO exercises that will follow it, are wargames. They are, in other words, fantasies, yet executed with extreme professionalism by soldiers equally convinced they are deterring a genuine threat. In many ways that is a metaphor for current Russian-Western relations, in which so many smart and dedicated people are engaged in driving forward policies structured around heavily mythologised images of the threat from the other side.