Lukashenko is able to repress the opposition, but can he manage the economy of Belarus as well as he manages the crack-down of society? According to our columnist Mark Galeotti the dictator has no coherent economic plan. Therefore his regime will be forced into an ever closer alignment with Russia.

Opposition leader Maria Kolesnikova on trial in Minsk (picture twitter)

Opposition leader Maria Kolesnikova on trial in Minsk (picture twitter)

OMON riot police on the streets, protesters in prison or exile, and tough rhetoric on TV have all helped embattled Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko weather the immediate crisis that followed his rigged elections of 2020, but the long-term survival of his regime will depend on the economy. Can this increasingly authoritarian system manage an economy as well as it manages a crack-down?

The challenges, after all, are numerous. Lukashenko’s legitimacy with his population is limited enough. If they face serious shortages or a rapid decline in their standards of living, they may well again take to the streets. If they do, Lukashenko will again be depending on his security forces: the KGB political police, the OMON and the rest of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and, as the final backstop, the army. They expect to be paid and housed, offered perks and medals, now that they are so crucial. (So far, at least, Lukashenko seems happy to oblige: unofficial reports talk of police getting on average 15-20% bonuses).

Under pressure

The West has been applying increasingly severe and sharply-targeted sanctions, and while Lukashenko may affect defiance – ‘you will choke on these sanctions,’ he said during his recent annual press conference marathon –the truth is that this is having an increasingly evident impact on Belarus. The economy is essentially stagnating, with recent figures showing a 2% growth quite possibly over-stated the case. Foreign debt is around the $18 billion mark. Half of this is owed to Moscow, and while Lukashenko may feel so far that Putin is unlikely to call in his markers just yet, there are wider concerns about the overall impact on the economy, and a shrinking range of options at Minsk’s disposal.

For example, suggestions that the potash industry, the country’s largest foreign currency earner, can simply re-orient to new markets in China and elsewhere, omit the fact that the threat of secondary sanctions mean that many companies will want to avoid being seen to work with Belarusian suppliers lest they also be targeted. Ironically enough, Russia is likely to be a beneficiary, whether snapping up markets lost to Minsk, or gaining new transit business as Belarusian exports can now no longer be moved through Lithuanian ports.

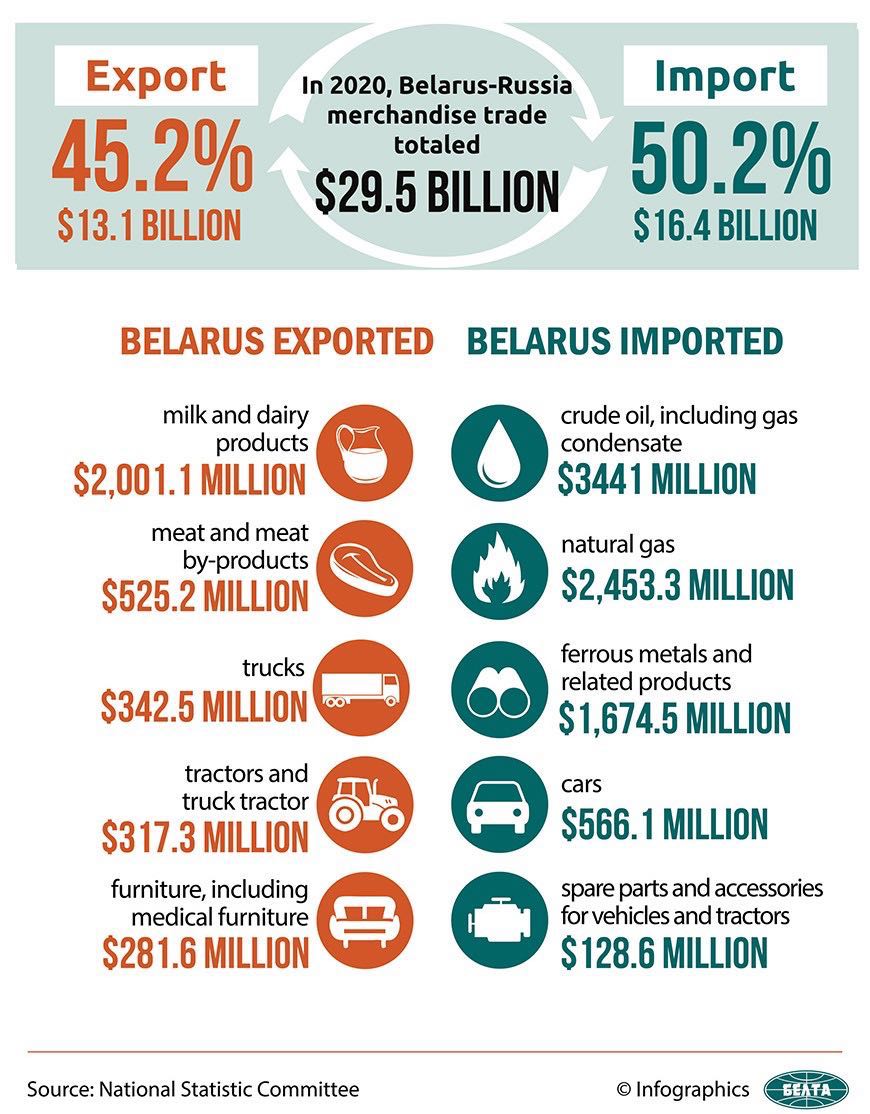

Trade balance Belarus-Russia. Government approved graphic by Belta

Brain drain

At the same time, the new mood in the country has accelerated a brain drain among those able and willing to find new lives in the West. This has hit the country’s IT sector badly. Especially since 2017, when tech companies had most of their tax liabilities waived, Minsk has emerged as an unlikely IT hub, whose Hi-Tech Park scheme saw more than 1,000 tech companies with over 70,000 workers register to operate in Belarus. The World of Tanks online gaming phenomenon, the Viber calling app and a host of other services and developments had their genesis in Belarus.

In 2020, the sector recorded a 25% year-on-year growth, with $2.7 billion in exports, accounting for 4% of national GDP. However, this is a very mobile, dynamic and volatile sector. Companies can easily relocate and their star programmers are welcome across the world. Although the closing of Belarus’s borders at the end of 2020 was presented as a pandemic response, it was as much as anything else intended to reduce out-migration. All the same, the best and the brightest can get out – and more than 15,000 of them reportedly already have.

Slow-burn problems

These are all slow-burn problems for Minsk, though: they are likely to eat away at the state, but as authoritarian regimes around the world have demonstrated, so long as their elites remain sufficiently united and their security forces sufficiently loyal, they can survive years of such pressure.

On the other hand, a liquidity crisis would have a potentially rapid effect, if people could not get money out of banks to pay for food and other necessities, or if there were a sudden run on the Belarusian ruble. As is, the national bank’s reserves of foreign exchange could cover only two-thirds of the total currency deposits held in banking sector’s private and corporate accounts.

It is to a large extent to avoid this danger that the Kremlin – which sees Lukashenko as the lesser of two evils, compared with another ‘people power’ street revolution – continues to provide loans and debt relief. Perversely, Minsk has also just received $900 million from the IMF, part of the funds it provided members to help fund their response to Covid-19. However unappetising, Lukashenko’s regime is still the internationally-recognised government of Belarus.

There is talk of optimising benefits from past investment, of new opportunities for cooperation with China (including bidding for loans from the Eurasian Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China), of support for new ventures. Yet at the same time, it is clear that much of that old investment was wasted, Beijing is not about to do Minsk any favours, and corruption and the primacy of political repression often gets in the way of any efforts to generate new business. In April, for example, Imaguru, one of the key start-up hubs in Minsk, was effectively shut down, apparently because its owners spoke out against political repression.

Man without a plan

Overall, there is little-to-no evidence that the regime in Minsk has any coherent, serious or long-term economic plan. It is focused on survival and the short term. To a large extent that simply seems to mean continuing to cajole, beg and lever Moscow into continued support.

Lukashenko and Putin in Sochi (picture Kremlin)

Lukashenko and Putin in Sochi (picture Kremlin)

According to the IMF, Russia subsidised Belarus to the tune of $106 billion between 2005 and 2015. Part of this was through preferential access to its markets: it is Belarus’s biggest trading partner, accounting for about half of imports and exports alike. Even more important have been discounted loans on favourable terms. However, a key role was played by waiving tariffs on oil exports and subsidising gas sales, together worth over $54 billion up to 2020. If anything, Russia had been looking to reduce the scale of its support for a regime it considered irritatingly wilful, and in January of last year it halted oil sales to Belarus for a time as part of lengthy and acrimonious negotiations over tariffs.

To some observers, this suits Vladimir Putin, as it makes Lukashenko increasingly dependent upon him. Up to appoint, this is true, although neither man likes or trusts the other, and Minsk remains stubbornly independent. Lukashenko’s continued refusal to recognise the annexation of Crimea, for example, is a mark of this complex relationship: he knows he depends on Russia, but he also knows the Kremlin now feels it cannot let him fall to the street. Likewise, those who see the best way of putting pressure on Minsk being to raise the cost to Moscow omit to consider that if Russia finds itself in effect bankrolling Belarus, it may feel it might as well assume the privileges of ownership as well as the cost. Annexation or merger is not something the Kremlin is especially interested in right now, but it may come to feel it is the least worst choice on an unappetising menu.

Who’s willing to get one’s hands dirty?

Justified indignation in the West; cynical cluelessness in Minsk; frustration in Moscow. The use of conventional economic statecraft to try and punish this toxic regime and force some positive change upon it may well actually push Lukashenko into increased repression, and Russia into ever closer alignment.

Yet while it is easy to dissect the weaknesses of current strategy, it is rather harder to create an alternative one: as much as anything else, Belarus stands as an example of the inescapable truth that it is hard to dislodge a ruthless and repressive regime unless one is willing to get one’s hands dirty, and so far it seems no one in the West is.