After days of rumours president Karimov has been officially declared dead. The funeral is September 3. Who will succeed him? Uzbekistan watchers are holding their breath. What will happen to the former Soviet-republic in Central Asia without the man who ruled the country with iron fist for more than a quarter century?

On Sunday, August 28, rumors began to swirl in the Russian and Uzbek language internet that Islom Karimov, President of Uzbekistan, had suffered a stroke. That was not unusual. In recent years, rumors about the 78 year old’s health had become commonplace. He was reported to have suffered heart attacks, to have succumbed to coma's; rumors even had it that he was dead and his public appearances were the work of a body double.

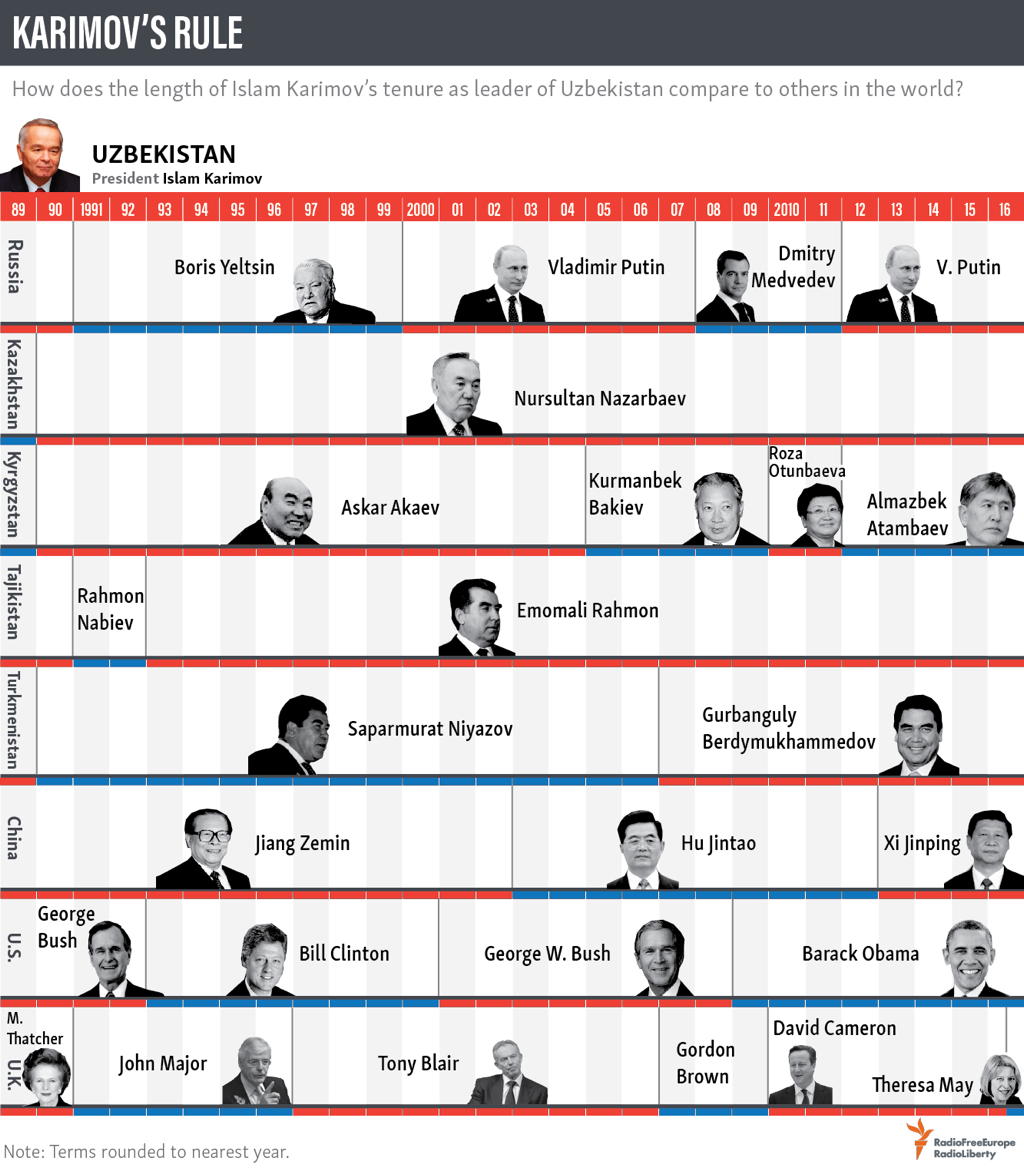

Islom Karimov, 25 year long dictatorship

Islom Karimov, 25 year long dictatorship

This time, however, Karimov’s serious condition was confirmed: first, by his daughter Lola, via her Instagram-account, and later by official Uzbek news sources, which announced gravely that the leader of the country was ill.

On september 2 his death was finally officially announced. The funeral will be on september 3. Uzbekistan watchers are holding their breath for the succession. For years they have tried to understand the maneuverings at the pinnacle of Uzbekistani politics and outlined possible scenario's for what happens next. Now it looks like they will soon find out. In all likelihood there is a battle going on already. It cannot be ruled out that Karimov has already died and the news is being withheld while the elite decides on steps to take next.

Who is Islom Karimov?

Islom Abduganeivich Karimov was born in 30 January 1938, and grew up in an orphanage. Karimov made his career in the state planning organs. In the 1980s, Uzbekistan had suffered a series of political scandals. From the late 1950s until his death in 1983 the leader of the Communist Party was Sharof Rashidov, a journalist and writer promoted and appointed by Nikita Khrushchev. A candidate member of the Politburo, the main decision-making body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and a close friend of Leonid Brezhnev, Rashidov was the most influential of the Central Asian leaders, and he used his influence to attract investments to his republic. In trying to meet ever-growing Soviet demands for cotton, however, he also allowed a huge system of corruption to flourish. Officials at all levels embellished the numbers of cotton sold to the state, collecting the money and pocketing the difference, or using it to develop patronage networks.

When Brezhnev’s successor Yuri Andropov tried to take on corruption, Uzbekistan was one of the focal points. Hundreds of party and state officials would lose their jobs, and many wound up in jail. What’s more, once Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and began to promote glasnost, or openness, newspapers and magazines began to write about the situation in Uzbekistan. All perverse consequences of the Soviet cotton economy were now into the open for the Soviet readership: not just the corruption (which took different forms in different republics, but was generally endemic to the whole country) but also the environmental pollution, the lack of mechanization, the use of child labor, and the damage to women’s health.

Uzbeks themselves had long been aware of these problems, but the exposes and purges coming from Moscow alienated the local political elite and many ordinary Uzbeks besides. Wasn’t it pressure from Moscow that brought the situation about? And wasn’t corruption endemic? Why should Uzbekistan be singled out? Rashidov’s successors did not last long – if they were seen to be doing Moscow’s bidding they had trouble establishing authority at home; if they were not they lost Moscow’s support. It was in this context that Karimov became first secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan in 1989.

Brief experiments with democracy

Karimov reluctantly oversaw the brief experiments with democratization, allowing several opposition groups to function. In 1990 he was elected President of the Uzbek Soviet Social Republic by the republic’s Supreme Soviet. Like most of the republican leaders, he bided his time during the August 1991 coup attempt in Moscow. When it failed, he declared Uzbekistan’s independence, staying ahead of the nationalist and pro-democratic forces that might have challenged him on the grounds of being a Moscow princeling.

Since then he has stayed in power by sidelining opponents, manipulating regional leaders, and extending his presidential term through various modifications of the constitution. Observers often talk about regional 'clans' that hold power in the country, and Karimov as a figure who stays in charge being their arbiter. Karimov himself is from the Samarkand region, for example, and relied on the patronage of Samarkandi officials in his early years; later he promoted the so-called 'Tashkent clan' to balance out the influence of his original patrons.

Overall, Karimov has one of the most repressive regimes in a region not known for democratic pluralism. Although he has avoided the leadership cult promoted in neighboring Turkmenistan under Supramurat Niyazov (Turkmenbashi - Father of Turkmenistan), he nevertheless maintained a personalized dictatorship. The choice of books in some stores in the capital seemed limited to books about the president, ghostwritten or at least endorsed by the president.

The media were tightly controlled. International computer experts were brought in to set up and maintain surveillance of the country’s internet users.

Divide and rule

In terms of foreign policy, Karimov has successfully played off foreign powers against each other. Karimov’s Uzbekistan engaged with foreign powers, but decidedly on its own terms. After 9/11 it offered NATO forces the right to open a military basis to assist with operations in Afghanistan in return for military aid and training. When US officials criticized Karimov for the bloody crackdown on protesters in Andijan in 2005, however, he told them to get lost, and take their troops with them.

At the same time, Karimov could at least claim, until recently, that economically Uzbekistan had performed better than many of the other post-Soviet states. Ofcourse, the cotton economy with all of its ugly consequences is still there. But by restricting privatization in the 1990s Uzbekistan was able to avoid the steep drop of GDP experienced by others. Gas exports helped too, once hydrocarbon prices began to rise in the 2000s. And the country was able to attract investments from international firms to set up automobile production and other plants.

In recent years, though, even these relatively meager achievements have proven to be fragile. Hydrocarbon prices have fallen, demand for other Uzbekistani products is low, and Russia’s financial crisis caused a drop of demand for Central Asian migrant labor and lower salaries for those who do find jobs. The national currency, the som, has fallen precipitously from 2500 to the euro in 2012 to 3500 in 2016. At the black market a euro costs up to 6000 som. State employees have gone months without salaries.

Rustam Inoyatov

Rustam Inoyatov

Succession Scenarios

Like many dictators intent on staying in power for as long as possible, Karimov has avoided naming a successor. Doing so could mean giving up one’s own power, as everyone tries to gain favor with the successor. Transfer of power within the family, of the kind that took place in Azerbaijan and now apparently is being set up in Tajikistan, is not an option. Karimov has two daughters. Even if transfer of power to a daughter was possible in the masculine political culture of Uzbekistan, neither of Karimov’s is a likely candidate. Gulnara Karimova, the more famous one, was briefly discussed as a possible successor, but this may have been a fantasy of pundits (and perhaps her own). She was most famous for her pop albums and music videos, as well as for using her position to attract bribes from foreign investors. In the Netherlands, were she had registred two of her firms, Gulnara even became involved in a lawsuit. Her reputation eventually became so bad that her father effectively disowned her, putting her under house arrest in 2014.

Uzbekistan watchers generally assumed that after Karimov's death the representatives of various regional alliances would get together and agree on a successor that was acceptable to all of them. Such regional alliances are not the only possible base of support, however. Uzbekistan has strong government institutions, in particular its security agencies, that will play an important role in any succession and ensuring stability.

Intelligence officer

Most observers agree that there are three powerful individuals who are likely to play a key role in the succession. The first is Rustam Inoyatov, an intelligence officer who rose to power in the 1990s and consolidated control in the fifteen years since. He is credited with turning the SNB, the KGB’s successor, into the country’s most powerful security service; his personal influence extends to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and even the military. According to a cable released through wikileaks, US diplomats saw Inoyatov as 'one of two or three top power brokers in Uzbekistan, a key gatekeeper to President Karimov and a decider of issues large and small that do not necessarily fall under a strictly intelligence purview'.

Yet Inoyatov is relatively old (72) and while he is likely to be involved in any transition it does not seem he will go for the job himself. More likely, he will try to hold on to his power behind the scenes.

That leaves two other potential candidates: Shavkat Mirziyoyev and Rustam Azimov. Mirziyoyev has been prime minister since 2003 and the former head of the Samarkand region. Before that he was the governor of Jizzakh District. The prime minister will lead the funeral procession, which means that his omen is good.

Mirziyoyev with Putin

Mirziyoyev has been able to maintain Karimov’s trust in part through self-effacement – he reportedly never challenges the president and always portrays himself as executing the president’s wishes. Indeed, his political instincts resemble those of Karimov – as governor he reportedly beat up a farmer who complained about conditions in the province. As prime minister he is in a strong position to succeed the president, but it is unclear if he has enough of an independent power base and support within the security institutions. Mirziyoyev’s longevity, however, suggests that Inoyatov feels comfortable with him near the formal pinnacle of power.

Economist and banker

Rustam Azimov is, at 56, the youngest of the three. An economist by training, he headed Uzbekistan’s central bank after independence, and has stayed in various finance-related posts since. Since 2005 he has been the minister of Finance, and since 2008 he has also held the post of first deputy prime minister. Azimov is seen as a competent technocrat, respected by foreign diplomats and the international institutions that have dealt with him for the last 25 years. Of all three he is most likely to pursue a reformist course, but he has no real power base. Should he succeed Karimov, it will be because Inoyatov decides that a technocrat would be easier to control than Mirziyoyev. (It was reported that Azimov had been arrested earlier this week, but his ministry has since denied that rumor).

Azimov is the only candidate who would attempt serious economic reforms. None of these three, however, is likely to undertake a major political liberalization of the country. Anyone who comes to power would be dependent on the support of the security services, especially in their first months. More importantly, the elite is united in its assessment of existential threats to the country and themselves. The country held together when neighbour Tajikistan was engulfed in civil war; it has largely avoided the ethnic and political unrest that Kyrgyzstan has faced. With reports of Uzbek fighters active in ISIS and Afghan militants becoming more active in northern provinces, some of which border Uzbekistan, there will be very little incentive to experiment with opening up political space.