In Russia we witness a slow reevaluation of Stalin as victor of World War II. It is part of a rewriting of history. But the Stalin terror poses a problem. As long as Russia doesn't cope with its totalitarian past it will not become a country where human rights are respected, says Nanci Adler.

by Nanci Adler

A walk down the sidewalks of Berlin or Moscow reveals a palpable contrast between the German and Russian approaches to their repressive history. Among its many commemorative symbols, Berlin’s sidewalks solemnly display over 5,000 ‘Stolpersteine’ (stumbling blocks), marking the homes where the victims of Nazism once lived. Inscribed on these blocks are their names, birthdates, deportation points, and dates of death. Over 50,000 such stones have been placed in other European cities. Post-Nazi Germany’s full acknowledgement of its repressive history – impelled by defeat -- permitted it to progress toward a democratic political system.

By contrast, post-Soviet Russia had no similar challenge to its repression of individual rights. Consequently, efforts to bring the Stalinist terror into the public space have been sparse, and are often marginalized. In fact, twenty-five years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the achievements of the Stalinist system, and Stalin himself, are still -- or again -- being acknowledged, and even valorized.

No more than 30 plaques

Nevertheless, small but significant counter-currents have been provided by the anti-Stalinist organization Memorial and other NGO’s who have subverted official attempts to ignore or co-opt the history of repression. In 2014, they orchestrated a campaign, entitled ‘Last Address’, offering individuals the chance to place a name plaque on the buildings from which their relatives were removed, often never to return. These silvery-grey plaques display eight spare lines, for example: ‘HERE LIVED VLADIMIR ABRAMOVICH NIKOLAEV; PEDIATRICIAN, BORN 1902, ARRESTED 1936, EXECUTED ON 19/12/1938;

REHABILITATED IN 1961.’ To the left of the text, a starkly empty square has been cut in the metal, representing the void the repression created in the families of millions of Soviet citizens, arrested without warning and executed or incarcerated. It also represents the void created by the official avoidance of what actually happened.

As of 2015, there were no more than 30 plaques in Moscow, each also representing a renewed struggle with the authorities – this time for permission to hang them. In post-Soviet Russia there is a persistent trend to manage national and public memory by repressing, controlling, or even co-opting the memory of repression.

Gulag museum

Until last year, there was not one state-sponsored commemorative plaque in Moscow to victims of Stalinism. Now a well-funded Moscow-city sponsored Gulag museum opened in October 2015. The museum’s depiction of human rights abuses within the Gulag is fairly accurate, but it avoids mentioning that the system of repression that existed outside the Gulag was the modus operandi of Soviet rule.

Zaal in Goelag museum in Moskou (foto vrij van rechten)

Zaal in Goelag museum in Moskou (foto vrij van rechten)

Moreover, while the museum addresses the crimes under Stalin in elaborate exhibits, it neglects the legacy of Stalinism that found expression in the persecution of the dissident movement of the sixties, seventies, and eighties. That history is not on display.

Revision of the past has been the short-term remedy to circumvent the obligation to undertake ‘transitional justice’ measures in post-Soviet Russia. The fashioning of a good future out of a ‘bad past’ has been facilitated by the construction of a ‘usable past’ for the national narrative.

Today the history of the crimes of Stalin and Stalinism have been so successfully glossed over that nationwide polls show his popularity edging back toward its pre-deStalinization levels. In a 2014 Russian survey, half the respondents rated Stalin’s role in the country’s history as positive. In a 2015 poll, 38% of those asked responded positively to the question of whether the Soviet peoples’ sacrifices during the Stalin era were justified by the high goals and results that were achieved in such a short period. And finally, regarding Stalin himself, 40% polled this year did not consider Stalin a state criminal, and the Stalin era was associated with more ‘good’ than ‘bad.

Parallel process of rehabilitation

Thus, despite official measures that purport to criminalize pro-Stalin propaganda, the parallel process of rehabilitation of Stalin continues -- on busses, in monuments, in stores, in textbooks, and in the public space. And now the Communist Party has seized the opportunity to capitalize on this trend and the longing for order, by declaring 2016 to be the year of Stalin, and the ‘Stalin Spring’. This marks the 80th anniversary of the 1936 ‘Stalin Constitution’, proclaiming the primacy of the Communist Party, and several local parties have developed initiatives to better educate the populace on Stalin.

Such select remembrance led one liberal politician to cynically comment: ‘When they talk about the Stalin era, they imagine the holster at the side, but not the barrel to the back of their neck.’ 1936 marked the beginning of the notorious Show Trials that wiped out the leaders of the revolution, but I suspect these won’t be receiving much attention in the envisaged exhibitions.

So, the casual acceptance of repression has been successfully coupled with the valorization of Stalin. His rise in popularity was accompanied by a sequence of measures, including the 2009 restoration of an ode to Stalin engraved in a prominent Moscow metro station and the creation of a state commission to guard against the ‘falsification of history to the detriment of Russia’s interests’. These measures prompted the chief human rights watchdog organization, Memorial, to presciently argue in 2009 that, ‘de-Stalinization is Russia's acutest problem at the moment.’

Contesting history in labor camp Perm

The revelations regarding state-sponsored repression may not have been a major determinant in facilitating the collapse of the Soviet Union, but their importance might be assessed from the importance placed on censoring them. Accordingly, rather than following the European example of recognizing the victims and crimes of Nazism through commemoration, Stolpersteine, transforming campsites into memorial museums, and substantive compensation, the only museum on a former Gulag site was co-opted by the authorities to misrepresent the Gulag as a bulwark against fifth column subversives seeking to undermine the Soviet people. The labor camp Perm that Gorbachev had closed in 1987, was dedicated in 1995 as a museum, and in subsequent years substantially developed. Observers and participants in those years did not foresee that the government would view it as a threat that had to be eliminated.

Hoofdgebouw Perm-36, nu een museum. Foto Gerald Praschl

Hoofdgebouw Perm-36, nu een museum. Foto Gerald Praschl

In 2014, as the power and water were shut off by the authorities, and the camp’s watchtower bulldozed, it was evident that Perm’s physical survival was in peril. The survival of its factual history was also imperiled by a state-run television report featuring interviews with former guards who claimed that only traitors were incarcerated in Perm. Perm had become the latest battleground for contesting the history of the repression.

Official textbooks

Many Soviet leaders were concerned about de-Stalinization, and imposed limitations accordingly. The reforms a government imposes on curricula are clear indicators of what it wants students to learn about and from the past. It should be noted that though educational materials are fashioned to reflect the political views of the government, in practice, teachers still feel free to disregard the content of the official textbooks. The approved account of history taught in Russian high schools today is a sanitized version of the Stalinist past. Putin, who famously decried the collapse of the Soviet Union as ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century’ in a nationally broadcast address in 2005, was an influential advocate of this narrative. He later argued that Russia should not be made to feel guilty about the Great Purge of 1937, because ‘in other countries, even worse things happened'. Putin admitted that there were some ‘problematic pages’ in their history, but asked in the same breath what state had not had these.

This stance is part consequence and part symptom of the fact that Russia made no substantial attempts to come to terms with the legacy of Soviet Communism. On the one hand, it has been impelled to disapprove of repression by prominent Russians like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, Khrushchev, and Gorbachev, among others. On the other hand, its leaders and many of its citizenry have become dependent on repression to maintain stability.

Promoting patriotism

In 2008, in an effort to promote patriotism among younger people, a teachers' manual covering the period 1900 - 1945 was officially approved for use in schools. Achieving such a goal through the use of history required a considerable manipulation of the facts as well as contriving creative interpretations. Witness this revealing illustration of the systemic bias built into the state-sponsored narrative found in a 2012 manual, approved by the Ministry of Education. It instructed teachers to address the period of Stalinist repressions by focusing on: ‘what we built in the 1930s’. They were told to explain that ‘Stalin acted in a concrete historical situation, as a leader he acted entirely rationally – as the guardian of the system.’ Since the scope of the repression does not readily fit into the concept of ‘rational governance’, the manual suggests working the numbers a bit.

Great country, great past

In 2014 the Putin administration initiated the creation of a textbook whose narrative would present a ‘unitary vision’, emphasizing the role of Stalin as an ‘effective manager’. The central message was to be: ‘We are citizens of a Great Country with a Great Past’; Putin recommended that there be no ‘dual interpretations’.

However, while a culture of repression persists, there have been important political changes, which include the fact that Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago was made part of the high school curriculum. Together with similar works which were prohibited from being published in the Soviet Union, and even illegal to possess, it is readily available.

Notwithstanding all of its ambiguity, if not ambivalence regarding the Stalinist past, in 2015, the Russian government endorsed a bill on the remembrance of victims of political repression. It addressed memorialization, books of remembrance, data bases, archival access, and victim recognition and compensation. It allowed a monument to the victims of Stalin’s terror to be placed in central Moscow, and the city of Moscow allocated a building and funds for the construction of the Gulag Museum mentioned above. Along with these measures, the state supported a parallel ‘practical patriotism’, though it did not define precisely what that was. State support for a de-Stalinization program runs counter to the ‘militant patriotism’ it also endorses, so civil society is chronically tasked to monitor the Russian government’s words and deeds.

Foreign agents

Today the work of historians and civil society actors who challenged the official narrative of present or past events became more marginalized, and in some cases even dangerous. Memorial has been accused of political activities and targeted for official harassment for not having declared themselves ‘foreign agents’, in keeping with a 2012 law.

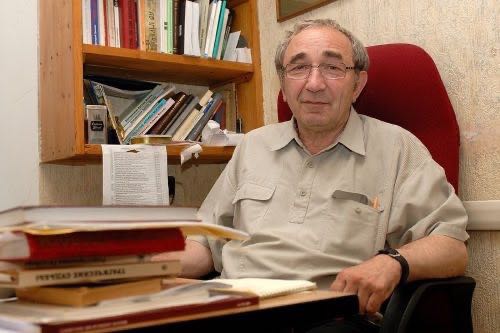

Historian Arseny Roginsky, chairman of Memorial, spent in Soviet times 4 years in labour camps (foto vrij van rechten)

Historian Arseny Roginsky, chairman of Memorial, spent in Soviet times 4 years in labour camps (foto vrij van rechten)

They share this politically precarious status with a number of other NGO’s. It appears that such statesponsored measures could severely limit the functioning of this human rights watchdog, which emerged during Gorbachev’s perestroika in 1987. At that time, Memorial set out to preserve and disseminate materials on the Stalinist past. It quickly went from being an organization that represented the victims of Stalinism, to becoming the most authoritative research center for recording, documenting, analyzing, and exposing the crimes of Stalinism. Their investigation of past human rights abuses also led to the investigation of present human rights abuses.

Memorial’s critical scrutiny of past and present violations is costing them dearly. In the last few years, the organization has been increasingly threatened with liquidation, but has dodged a number of bullets. The latest charge came from the Ministry of Justice, in relation to Memorial’s labelling of Russia’s actions in Crimea as aggressive. The organization was accused of of trying to overthrow the Russian government. In an interview I did last year with chairman Arseny Roginsky, he reflected on the predicament of the organization. He no longer characterized the state’s obstacles to its work as ‘battles,’ rather he termed them a ‘chronic condition’.

What can we conclude from all of this? While integrating the story of the terror into the mainstream history of Russia is a relatively straightforward task at the level of historical scholarship, it has been frustrated by political obstacles. Overcoming them would require a fundamental shift from a system of governance that devalues human rights, toward a democratic ethos that prioritizes them, which would include undertaking transitional justice measures.

However, the Russian government’s efforts to focus attention on the material and military benefits under Stalin and de-emphasize Stalin’s crimes suggest that promoting this skewed version of history is the best mechanism available for sustaining repressive governance. In consequence, organizations pursuing an accurate history of the Stalinist past are at risk for being charged with engaging in undesired political activity, and even of attempting to overthrow the Russian government.

Shared custody needed for social repair

Accordingly, the opening of archives (in Russia), or the proper placement of those records that have been accessed for, and produced by international tribunals, and the exhumation and forensic examination of mass graves, accompanied by gathering and analyzing personal and legal testimonies, would provide the public with the ‘shared custody’ of a ‘common past', necessary for social repair. There is support, however limited, for such an approach in Russia. Arsenii Roginskii emphasizes the importance of the story we tell to ourselves and to others: ‘society and the state will need to work together, and historians bear a special responsibility in this process’.

And so, in a final note, it may be that an inclusive history that recognizes the victims and their heirs, while it verifies, analyzes, records, acknowledges, and seeks to understand the competing narratives on the past could facilitate a shift from dueling monologues to engaging dialogues. Such a common undertaking might move Russia beyond the post-Communist impasse.

Dit is een ingekorte versie van de oratie die Nanci Adler op 14 april hield ter gelegenheid van haar benoeming tot hoogleraar Herinnering, geschiedenis en recht in relatie tot regimewisselingen aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam.