De Russische revolutie van 1917 was een keerpunt: voor Rusland zelf, en voor de rest van de wereld. Al honderd jaar zijn oorzaken en gevolgen onderwerp van debat. Voor RaamopRusland schetsen verschillende historici dit jaar hun visie op 1917. Na Marc Jansen, Boris Kolinitski en Sergej Podbolotov schetst Igor Torbakov de historiografische dilemma's voor het Kremlin nu. Deel 4 uit een reeks.

Remembering 1917: a matter of national security

The centennial of the Russian revolutionary events of 1917 is presenting the Kremlin with a difficult dilemma. Vladimir Putin’s regime simply cannot ignore one of key points of Russian history, and yet it seems to be struggling to fit the story of 1917’s political upheaval into its preferred historical narrative, which puts a premium on stability. One saying goes that revolutions are started by politicians, but it is historians who end them. In Russia the historians are not yet ready to finish it off.

The centennial of the Russian revolutionary events of 1917 is presenting the Kremlin with a difficult dilemma. Vladimir Putin’s regime simply cannot ignore one of key points of Russian history, and yet it seems to be struggling to fit the story of 1917’s political upheaval into its preferred historical narrative, which puts a premium on stability.

One saying goes that revolutions are started by politicians, but it is historians who end them. Myths often shroud revolutions, and it is left to historians to peel away the layers of fable to expose facts that can disturb long-held assumptions.

This was the case with the French Revolution: Francois Furet, an outstanding 20th-century French historian, challenged revolutionary myths in a series of highly influential books, and famously liked to proclaim that ‘the French Revolution is over.’ It also holds true for the American Revolution. The understanding of the American rebellion against King George III has undergone a vast shift in the past 50 years, thanks to historians like Bernard Bailyn, who famously recast the revolution not only as a war for home rule, but also one over who should rule at home.

In present-day Russia, however, historians are not in the lead when it comes to interpreting the past. It is Russia’s political and security elite that is in charge of elaborating a ‘correct’ interpretation of history.

According to Russian media reports, Putin’s Kremlin considers the question of how the 1917 centennial is observed to be a matter of national security. Late last year, media outlets reported that experts on the scientific committee at Russia’s Security Council discussed the centennial, and determined that the government needed to take steps to control the narratives, driven by a belief that outside forces were intent on intentionally distorting the revolutionary era, as well as other important periods of Russian history. The committee reportedly concluded that historical memory becomes an object of ‘deliberate destructive actions on the part of foreign government agencies and international organizations which seek to pursue their geopolitical interests through conducting the anti-Russian policy’.

Besides the Russian revolutions of 1917, the Security Council’s experts identified several other significant historical themes as vulnerable to falsification and in need of protection. These are the nationalities policy of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union; the Soviet Union’s role in the defeat of Nazi Germany; the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact; and the Soviet reaction to the political crises in the GDR, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and other former East bloc countries.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 1974. Foto Wikicommons

Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 1974. Foto Wikicommons

Solzhenitsyn set Putin’s agenda

It is eminently telling that the Russian General Staff drafted the key presentation at the Security Council’s session on the national security implications of the manipulation of history. Remarkably, speaking in late January at the first meeting of the Jubilee Committee for the preparation of the 100th anniversary of the Great Russian Revolution, Vitaly Tretyakov, a conservative political commentator, bluntly suggested that Russia’s national interests would be better served if historians were sidelined in the process of appraising the sociopolitical outcomes of 1917. It would be ‘unwise and unfair’, he contended, to give historians a free hand in shaping public attitudes towards the revolution. Tretyakov cited two reasons to support his argument: ‘First, for the most part today, as always, historians are ideologically biased. And second, they are not political thinkers.’

Whatever the shortcomings of professional historians, Russian authorities appear to be at a particular loss when it comes to marking the centennial of the Bolshevik Coup in November 1917 (October under the old style). Prior to that event’s 90th anniversary, the Kremlin opted for a seemingly ‘simple’ solution: in 2004, it swapped an old revolutionary holiday on November 7 for a newly invented nationalist one on November 4 – National Unity Day, which commemorated the expulsion of Polish occupation forces from Moscow in 1612.

Curiously, this decision coincided with the publication of a book, titled Sociosophy of Revolution, by Igor P. Smirnov, a Russian literary scholar based in Germany. In his study, Smirnov offered a highly unorthodox interpretation of False Dmitry’s reign and the Time of Troubles, contending that it was Russia’s first revolution. It is unlikely that the Smirnov study had any impact on the Kremlin’s politics of memory, but the routing of the Poles, and the establishment of an autocracy in the form of the Romanov dynasty’s 300-year rule obviously seemed like a good thing to celebrate.

However, the new holiday idea proved to be highly unpopular, and the Kremlin, unnerved by ‘color revolutions’ in Georgia and Ukraine, shifted its approach in a clear attempt to bring subversive revolutionary ideology into public disfavor. On February 27, 2007, the government daily Rossiyskaya Gazeta published Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Reflections on the February Revolution. For Solzhenitsyn, a conservative-monarchist, February 1917 was nothing more than a ruinous prelude to the catastrophic October. So his essay (originally penned in the early 1980s) unambiguously cursed the entire revolutionary period and mourned the loss of stability, sovereignty and the statehood of ‘historic Russia’.

February – harbinger of October?

Ten years on, political upheavals in the world, including Ukraine’s Euromaidan uprising, seem to indicate that the specter of revolution cannot be ignored. At the same time, Russian leaders do not have a clear message to convey. A sign of this confusion is a recent article written by Sergei Mironov, a Putin ally in the State Duma.

Mironov’s essay, titled February – a Harbinger of October and published in Nezavisimaya Gazeta, seems to demonstrate the Kremlin’s growing ‘poverty of philosophy’. It is a disjointed assembly of contradictory theses. Mironov acknowledges the February Revolution’s positive achievements, including the establishment of a republican form of government and the recognition of political rights. But he also bemoans the downfall of tsarism, claiming the February Revolution caused the erosion of traditional Russian values. ‘Power lost its sacredness’ in 1917, he also laments. He goes on to add, referring to the chaos that accompanied the Soviet collapse, that ‘the same devastating effect of the spiritual and ideological crisis we observed in the 1990s’.

Former czar Nicolas II and son Alexey in Siberian exile in 1917. Foto Wikicommons

The chief lesson Mironov draws in his analysis of 1917 is that Russia requires a strong hand at the helm of state. ‘Russia is not a country that can afford to have a weak power, led by such a weak-willed ruler like Nicholas II’, he wrote. ‘It is a great boon for all of us that in the current difficult times the country is ruled by such a strong personality as President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin.’

Mironov’s conclusion fails to take into account an important fact: as 1917 (and 1991) showed, autocratic regimes may be outwardly strong, but can be inwardly brittle, and can therefore collapse with startling speed. Autocracy tends not to supply enough glue to keep the social fabric together during times of economic and political stress. ‘Rus’ has faded away within two days. At most, within three’, the Russian writer Vasily Rozanov incredulously noted in 1917.

Uncomfortable questions for current regime

The divergence between the image of the Russian Empire’s greatness and its ingloriously swift demise should raise uncomfortable questions for those who support a new form of autocracy in Russia. The history of the 20th century shows that autocracies and authoritarianism can be more brittle and more susceptible to sudden breaks than other systems that allow for broader public participation.

Russia’s present-day leader, Vladimir Putin, would love nothing more than to be seen as the heir to the power and glory of the halcyon days of the Romanov dynasty that was toppled back in 1917. Yet, the system that Putin presides over, in its shape and form, is more of an outgrowth of Soviet Communism than a link to Russia’s tsarist tradition.

This dichotomy is the primary reason why Kremlin ideologues find themselves in an awkward position these days: in the historian Mark Edele’s words, the tumultuous events of 1917 ‘can neither be fully embraced, nor fully disowned’ by today’s Kremlin.

Putin’s love-hate affair with Bolshevism

Putin clearly has a love-hate relationship with Bolshevism. On the one hand, he has stated that he is no great fan of Lenin and his followers. He has described the Bolsheviks as traitors who sabotaged Russia’s war effort in World War I – something that ultimately led to Russia’s ‘losing to the losing side’. He has likewise heaped scorn on their domestic and economic policies, and characterized Lenin’s nationalities policy as a time bomb that detonated in 1991, causing the Soviet Union’s collapse.

At the same time, Putin has remarked that he ‘very much liked, and still likes communist and socialist ideas’. Moreover, Putin is proud of his membership in the Communist Party, as well as his 20 year service in the KGB – an agency that was, he once said, seemingly with pride, ‘the successor organization to the Cheka’ and widely known as ‘the Party’s armed unit’.

The contradictory views held by Putin are not just the result of cognitive dissonance. The Kremlin’s ambivalence about the revolutions of 1917 stems from ambiguity relating to Russia’s post-Soviet identity.

In terms of cultural identification, Putin’s Russia yearns to reconnect to the lost world of the Romanov dynasty. The Russian Orthodox Church has canonized Nicholas II, and Putin now stages pomp-and-circumstance rituals that clearly strive to evoke a sense of tsarist-era grandeur. But there is no escaping the fact that in purely legal terms, the present-day Russian Federation is a direct successor of the Soviet regime. The reality is that the Bolshevik decree of November 22, 1917, abolishing all laws of the Russian Empire, retains its validity. That decree erased centuries of tradition from Russia’s legal memory.

The way post-Soviet Russia handled the issue of property rights underscores the strength of the Soviet legacy. Russia’s economic relations today rest upon the decision made following the Soviet collapse in 1991 to recognize the legality of Soviet notions of property, i.e. that land, structures and enterprises belonged to the state, not individuals. It was then easy for all such ‘state’ property to be privatized, as if it had previously never belonged to anyone. The privatization that occurred in the 1990s, then, ignored the rights of tsarist-era owners who had seen their property arbitrarily expropriated by the Bolsheviks.

The decision to not offer redress for the Bolsheviks’ ‘nationalization’ of property continues to have adverse ramifications today in that it abets an atmosphere of lawlessness and insecurity when it comes to property rights. A dynamic economy cannot be constructed unless property rights are secure and uniformly applied.

Time for moral and historical assessment

Notwithstanding the Putin administration’s occasional criticism of past totalitarian practices, the Communist era of Russian history has yet to receive a comprehensive moral and historical assessment. The Communist regime’s many crimes have never been repudiated and condemned, and, as a result, no acts of national atonement have occurred. One could even argue that the process of the Russian nation’s moral revival has not yet begun.

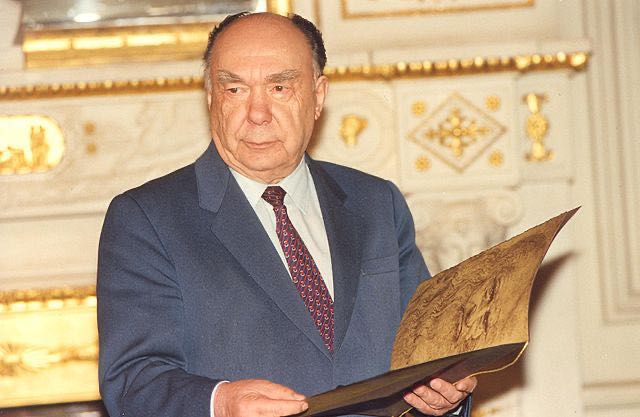

Alexander Yakovlev (1923-2005). Foto Wikicommons.

Such a perspective was held by Alexander Yakovlev, one of the leading ‘architects’ of perestroika, the reform drive in the late 1980s that aimed to make Soviet-style Communism more efficient, but which ultimately sowed the seeds of the system’s demise.

Not long before his death in 2005, Yakovlev was interviewed by Jonathan Brent, who at that time was the editorial director of Yale University Press and founder of the Annals of Communism series.

‘In conversation’, Brent wrote in his 2008 book Inside the Stalin Archives, ‘Yakovlev always returned to the fact that Russia was never fully de-Sovietized. There was no Nuremberg trial, no general accounting, no public reconciliation between victims and victimizers, no restoration of property, or adequate compensation to the many millions whose lives were permanently damaged or destroyed by [Lenin’s and] Stalin’s ‘utopia’.’

‘Instead the country drifted into indifference and forgetfulness, hardly knowing whether it wanted freedom or not – hardly remembering freedom at all’, Brent added.

Ambiguous stance towards past and future

The Russian leadership’s ambiguous stance toward the revolutions of 1917 is also a byproduct of its inability to formulate an inspiring vision for the future. What is present-day Russia’s social ideal? Where is it heading? Some segments of the Russian political elite style themselves as supporters of conservative ideas. But conservatism presupposes respect for institutions. Others say they are the champions of a political system that is led by the wise and strong ‘national leader.’ But an ideology built upon a charismatic leader demands a grand vision.

Ultimately, post-Soviet Russia is not a country that holds institutions in high esteem; nor is it the home of big ideas. Incapable of generating a compelling vision for Russia’s future, the country’s leadership is mainly concerned simply with perpetuating its own power.

As a result, Russian claims to Great Power status, as well as the Kremlin’s domestic emphasis on centralized authority and the preservation of stability above all else, are built upon an eclectic historical foundation, developed from a mish-mash of the Soviet and tsarist past.

Originally published as series of two articles by EurasiaNet.org.

This is the fourth article on the Russian revolution. Earlier RaamopRusland published interviews with Sergey Podbolotov and Boris Kolonitsky and an essay of Marc Jansen.