Russia's ruling party United Russia has lost most of its credibility by now, after the highly impopular pension reform and the political protests of the summer of 2019. Being with United Russia is not good for your reputation anymore. But for Putin the party is an irreplaceable element of his vertical of power. And so there will be no changes and no alternatives, as the last party congress showed. With two years to go to the next elections domestic politics in Russia equates authoritarian administration. No room for initiative, flexibility or freedom, argues political analyst Tatiana Stanovaya at Carnegie Moscow.

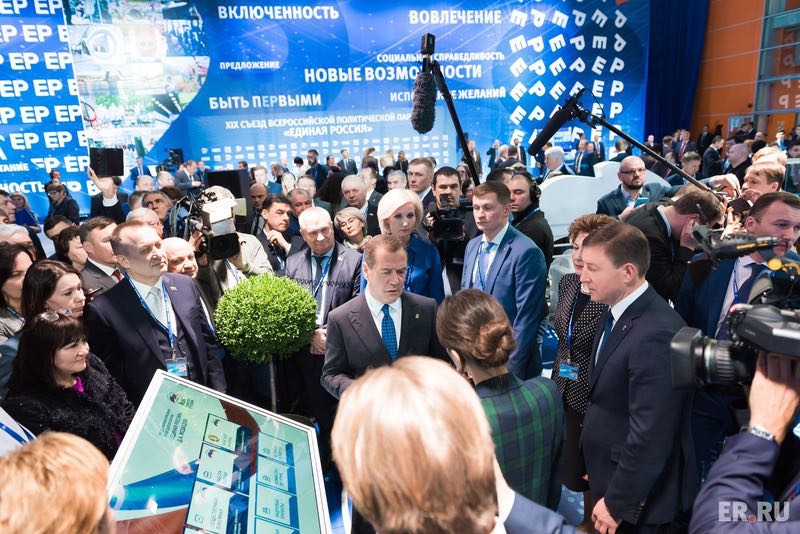

Premier Medvedev at the 19th Partycongress of United Russia in November 2019 (picture United Russia)

Premier Medvedev at the 19th Partycongress of United Russia in November 2019 (picture United Russia)

The fate of the United Russia ruling party has long been under discussion, following a slump in its ratings and electoral defeats for its candidates: will it be replaced with some kind of new project, merged into a broader coalition, or put to the side completely? The party’s annual congress that took place in Moscow on November 23, therefore, was expected to shed light on the Kremlin’s plans for the party. After all, in many ways, the endurance of the regime itself depends on the strength of the party’s position.

In the last eighteen months, United Russia has undergone two difficult experiences. The first was the unpopular move to raise the retirement age. The main political responsibility for this fell on United Russia, since the government pushed through the reform in silence, and President Vladimir Putin only expressed his support for it at the final stage. The party’s rating, which had long hovered around 50 percent, began to fall rapidly after the pension reform in 2018, and since the beginning of this year has been around 33 percent, according to data from the state pollster VTsIOM. The president and government have also seen their popularity decrease, but the slump in United Russia’s ratings puts in jeopardy the regime’s control over the federal and regional parliaments.

The second difficult experience was the exodus of the elite from the party. In September’s regional elections, six out of sixteen governors ran as independents, while in the elections for the Moscow city parliament, there was not a single candidate from the ruling party. If previously not standing as a United Russia candidate was the preserve of the most prominent politicians, such as Putin and Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, now it is becoming the norm. Being associated with United Russia creates a negative ballast in terms of reputation, pulling ratings down. United Russia was turning into something antiquated and half-abandoned that it started to seem a shame to throw away, but shameful to show.

Still, so far, nothing other than a powerful ruling party has been invented. Its significance for maintaining the regime’s stability is simply too great.

Attempts for rehabilitation

The turning point came in the regional elections on September 8, when, in the words of the party’s general council secretary Andrei Turchak, 'United Russia trounced everyone'. That’s a debatable assessment of the situation, but also a symbolic one: it shows that the party’s curators regarded the election results as being entirely to their advantage. From that moment, attempts began to rehabilitate United Russia, and to restrict the trend for running as independents.

It proved impossible to dismantle the ruling party for two reasons. The first is the personal position of Putin. The president has publicly described United Russia as the crucial backbone of power. For Putin, United Russia is a verified and irreplaceable element of the political construction that requires unambivalent support at the highest level.

It’s no coincidence that the president attends the party’s congresses, despite the electoral risks, and that he is not afraid of continuing to associate himself with United Russia. This congress was no exception. Putin’s speech put an end to any doubts: the party will retain its place as an institution of power.

The second reason is more banal: any party or supra-party project seeking to become an alternative to United Russia is much more risky for the regime than keeping the status quo. The Kremlin firmly believes that United Russia has its core voters (about 30 percent of the electorate), which could be joined by those still sitting on the fence.

This idea was confirmed by a VTsIOM poll that was clearly timed to coincide with the United Russia congress, and which showed that two-thirds of the population believe that the country should have a ruling party, and that it potentially has the support of 60 percent of voters. No other party, no other project can compete, is the feeling in the Kremlin, which is inclined to underestimate medium-term political risks to the ruling party. Parties concomitant to United Russia may come and go, but they can never lay claim to the position of ruling party.

Building a power vertical

Since Putin came to power, the process of building a power vertical has always gone hand in hand with the formation of a pro-Putin party majority. But the creation of second ruling parties has nearly always been unsuccessful, from Rodina (Motherland) to A Just Russia. The Russian regime is used to dealing with a streamlined and clear hierarchy, not with political pluralism, even if it is all supportive of the ruling authorities. The fact of the matter is that management of domestic politics in Russia has turned into authoritarian administration, where there is no room for initiative, flexibility, or freedom.

Despite it being positioned as a pre-election event, no new ideological narratives, no ways of revamping the party’s image or new visions of the future were presented at the congress. The meeting of United Russia’s expert council held on the eve of the congress, at which preparations for elections to the State Duma in 2021 were discussed, was decidedly conservative in tone and focused on maintaining the status quo.

The council head, Konstantin Kostin, said that the main resources for improving the party’s ratings were its perception as 'Putin’s party' and the 'ruling party', the retention of its core voters, and the creation of conditions for winning over floating voters, as well as the party having the most far-reaching political infrastructure in the country.

For a party with a fragile rating at a time of growing discontent and unpredictability, simply keeping hold of what it has is a fairly feeble pre-election strategy. Administrative resources and Putin’s name remain the party’s main asset. United Russia and its rescuers have no intention of getting to grips with the new challenges of the future. Instead, they are searching for a way of returning to better times, when the party easily won a majority.

Technocratic rather than political

The injection of fresh blood into the party is also technocratic rather than political. Its main manager, Turchak, does not have his own ideological or electoral weight: he is a pure apparatchik, assigned to the party two years ago to reduce the influence in it of State Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin.

The party’s only political leader, outside of Putin’s informal leadership, is Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. He is apparently in agreement that without a ruling party, the regime will crumble, and so has begun actively aligning the party under his own vision. The ruling party will clearly retain its central place under any scenario for the future transition of power, and anyone who hurries to jump on the bandwagon today will likely come out on top.

In Russia, there cannot be any pre-election decisions two years before elections. Two years is a very long time, especially in the current situation. The real parameters of the campaign for the Duma will only begin to take shape after the regional elections in September of next year, and in that respect, the 2020 party congress will be more indicative and important.

The latest congress confirmed the wishes of the Kremlin and the president himself to rehabilitate United Russia and protect it from the destructive tendencies of the last eighteen months. But what the authorities are proposing is merely a rotation of political strategists and the political status quo: no reforms, no new meaning or projects for the future. They are attempting to preserve the ruling party in its former state from the top down, despite the new and more complex political reality.

In practice this means that United Russia will use administrative rather than political methods to achieve its result in the elections. The presence of the opposition will be minimal, with even less competition: everything that enabled United Russia to describe its showing in the last regional elections as victory.

United Russia neither has nor requires any other instruments to ensure its victory. But even for an administrative win of this kind, the Kremlin will have to work hard on further purging the political field: counteracting tactical voting, bringing the in-system opposition into even closer contractual arrangements, and driving out any critics of the regime from the playing field altogether. This is the price the regime must pay to preserve the ruling party: the foundation without which its stable existence cannot continue.