Colonel General Sergei Korolev, appointed as the new First Deputy Director of the Federal Security Service (FSB), is connected with organised crime in Russia. This was probably a deciding factor in finally elevating him, writes our columnist Mark Galeotti. Close ties to the underworld aren’t a problem. The Kremlin, concerned that Alexei Navalny could be an additional source of friction in a system already beginning to grind and groan, is looking for ruthless enforcers.

Sergei Korolev. Screenshot by Boris Yarkov

Sergei Korolev. Screenshot by Boris Yarkov

The appointment of Colonel General Sergei Korolev to become the new First Deputy Director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) may give us a hint on who will rise to head the service soon, and certainly tells us much about the Kremlin’s thinking about the role of the agency. However, it also marks a further degeneration of the so-called ‘new nobility’.

The FSB is, after all, a central element of Vladimir Putin’s power system, the weapon to be unleashed on any of his foes. When the boss wanted surveillance and subtler intimidation, that was what it did. Now that Putin seems to have moved into a new age of more direct repression, again it is the FSB that is at the force. It was the FSB that poisoned Alexei Navalny, that is currently trying to break up his national network, and that was behind the arrest of some 200 municipal deputies gathered to discuss electoral tactics in Moscow. It is more than simply a political police force, though: it has a significant role in the economy and helps shape the security discourse that even influences foreign policy and Putin’s wider understanding of the world. Nikolai Patrushev, the hawkish secretary of the Security Council, and the closest thing Putin has to a national security adviser, is a former director of the FSB, and its current director, Alexander Bortnikov, is another of the president’s key allies. It matters who is in charge of this institution.

In October 2020, FSB first deputy director General Sergei Smirnov retired quietly. It was no surprise that he was going to retire, as he had reached the age of 70 and was already in ill-health, but it was a surprise that he departed office with such a lack of fanfare and no comfortable sinecures. He was, after all, a powerful and influential figure within the Russian security community.

The Smirnov factor

Indeed, in many ways he was more influential in practice than Bortnikov. Whereas Bortnikov is the political director of the agency, Smirnov had made sure that he was in effective control of the most significant elements of the FSB – the Economic Security Service, the Service for the Protection of the Constitutional Order, and the Internal Security Directorate – through both the formal chain of command and the judicious appointments of henchmen and proxies.

The Economic Security Service (SEB), to put it bluntly, is the greatest generator of illegal rents within the FSB. The Service for the Protection of the Constitutional Order (SZKSiBT – typically just ZKS) is the most politically-important element, especially as the Kremlin becomes increasingly concerned about the opposition. The Internal Security Directorate (UVB) provides the best means for bringing pressure to bear on rivals within the service, as well as other security and law enforcement agencies.

The Economic Security Service is the greatest generator of illegal rents within the FSB

It would be hard to overstate Smirnov’s baleful influence, not least in terms of the continuing corruption of the FSB. Of course, he was as much symptom as cause. The agency has long had a problem with the inevitable temptations of extortion and embezzlement given its combination of power and impunity. It is also true that there are many essentially professional and honest FSB officers. However, they by definition both lack the extracurricular advantages of their more morally-flexible peers and also, to be blunt, embarrass and threaten them by their very presence.

Nonetheless, the much-decorated Smirnov – who had been a classmate of Security Council secretary Nikolai Patrushev and former Interior Minister and State Duma speaker Boris Gryzlov at Leningrad’s Secondary School No. 211 – is especially associated with the debasement of the UVB, the very agency meant to watch the watchers and fight corruption within the FSB. In many ways, it became little more than the extortioners’ extortioner, taking its cut from various corrupt schemes in return for turning a blind eye, and also an enforcer for hire.

Bortnikov, after all, is a hawk and a willing executor of the Kremlin’s political repression at home and subversion abroad. He also, reportedly, enjoys the usual lifestyle of a senior Russian businessman and it is widely assumed that the rapid rise of his son Denis to becoming chair of VTB bank owes at least something to his father’s position. However lukewarm an endorsement it may sound, though, by the standards of his peers, Bortnikov has a reputation as one of the more personally honest figures. In the words of one FSB veteran, 'he’s not especially comfortable with what’s happening in the service, the blatant corruption, the indiscipline, the obvious mercenaryism. But he doesn’t know what to do about it, and thinks it’s not as important as doing the [political] job'.

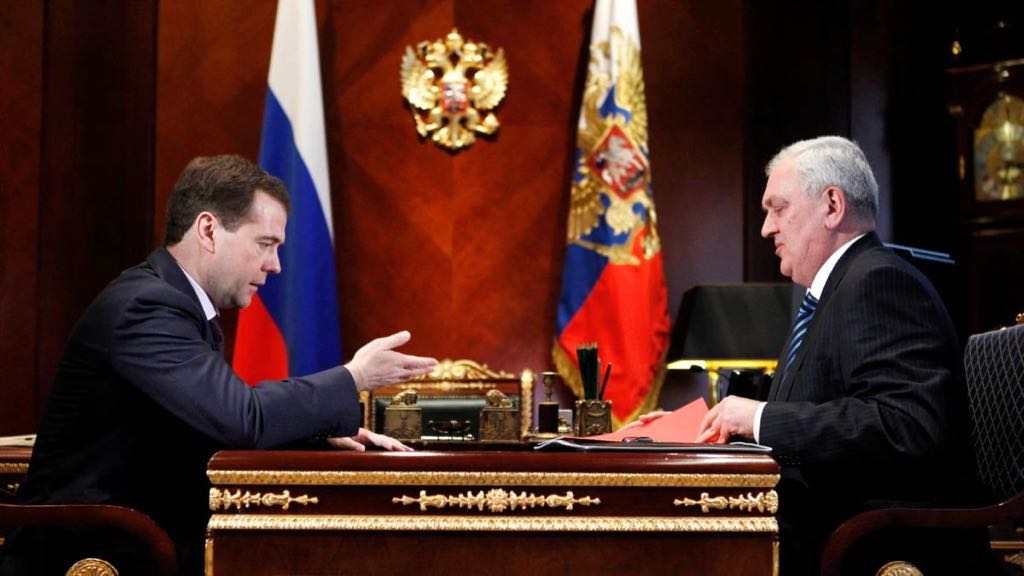

Sergei Smirnov with then president Dmitry Medvedev. Picture Kremlin

As Smirnov neared retirement, it was perhaps unsurprising that Korolev was soon being tipped as his likely successor. After all, Korolev was something of a protégé of his, as well as having the right kind of track record. He had worked in the Military Counter-Intelligence Directorate (UVKR), also part of Smirnov’s empire, and then headed the UVB. During his tenure as its chief, the UVB’s Sixth Department became infamous as the so-called ‘Sechin’s Spetsnaz,’ operating as the enforcers of Rosneft head Igor Sechin – a powerful figure in Russia, to be sure, but with no place in the FSB chain of command. This was precisely the 'mercenaryism' that dismayed – and embarrassed – Bortnikov, yet he seems to have felt he could do nothing about it.

FSB-chief Bortnikov is a hawk and a willing executor of the Kremlin’s political repression at home and subversion abroad

More broadly, the UVB was at the heart of a whole series of high-profile criminal cases that seemed to owe more to political score-settling and economic rivalries than security, including the virtual emasculation of the police’s Main Directorate for Economic Security and Combating Corruption (GUEBiPK) and cases against a range of local officials, including former Kirov governor Nikita Belykh, Komi’s Vyacheslav Gaizer, Sakhalin’s Alexander Khoroshavin, and Igor Pushkarev, mayor of Vladivostok.

In 2016, he was appointed to head the SEB. This follows the resignation of the previous incumbent, Yuri Yakovlev which, in turn, resulted from an investigation initiated by none other than Korolev’s UVB. His reputation at the time was, in the words of National Anti-Corruption Committee Kirill Kabanov, as a 'cleaner', in other words as someone who could clear up problems, whether in the interests of the Kremlin or some other patron or customer.

Nonetheless, his rise to heading the SEB, and now talk of him being a future successor to Smirnov – and even Bortnikov – Korolev, a man who until then had managed to avoid public attention, came increasingly into the public eye. Following his latest elevation, the independent investigative outfit Istories ran a lengthy article on Korolev’s alleged underworld contacts. In 2019, The Insider had run claims that Korolev was the mysterious ‘Boltay-leg’ referenced in intercepted phone conversations with Gennady Petrov, alleged kingpin of the Tambov-Malyshev crime gang (Petrov is wanted by the Spanish police but still at large, presumed to be in Russia). Istories took this further, charting what looks like a pattern of underworld contacts.

Reported involvement in the Golunov case (where a journalist was clumsily framed) may have temporarily stalled Korolev’s most recent promotion (he is the godfather of one of its initiators). Indeed, there were suggestions that the job could go either to the head of the Moscow and Moscow Region FSB directorate, Alexei Dorofeev (as a compromise candidate) or else someone drawn from Putin’s Praetorian Guard, the Federal Protection Service (FSO), such as its current head, Dmitri Kochnev. As it was, while the FSB is often involved in efforts to impose a varyag (‘Varangian’ – slang for an outsider brought in to bring a region or organisation to heel), it managed to resist falling foul of the same danger itself.

The debauchery of the ‘new nobility’

According to Istories, when Bortnikov heard of one of Korolev’s underworld relationships – with the gangster-vigilante Aslan Gagiev – he summoned him for a dressing down. One of Korolev’s friends reportedly said that, while ‘someone else would have started to play around somehow, to invent something, he told everything like it was. He acted like a man.’

Judging by other accounts, Bortnikov was not mollified, but felt he could not dispense with the well-connected Korolev. After all, there is a sense that the ‘top bench’ of the FSB is not looking especially replete with talent, and it is not as though the other senior figures are necessarily beacons of virtue. Korolev is at least considered to be tough, able and ruthless. This was probably a deciding factor in finally elevating him. There is much talk at the moment about the FSB being put in charge of everything from economic policy to political management.

Korolev is at least considered to be tough, able and ruthless

Much of this is over-blown. To be blunt, many of the attitudes embodied by the FSB can be found in all kinds of other individuals and agencies – or at the very least they have learned to be political chameleons and can easily adopt whatever colouration the times demand. Nonetheless, it is clear that the Kremlin is concerned about Alexei Navalny and the opposition. It is not so much that they pose a direct threat, as that they are an additional source of friction in a system already beginning to grind and groan under the pressure of economic stagnation, international impasse and a lack of long-term investment and vision.

Picture: author unknown

Picture: author unknown

In this context, the Kremlin is looking for enforcers, and there is substantial chatter to the effect that Korolev’s survival and then promotion – and with it the prospect of a coronation as Bortnikov’s successor when he turns 70 in November – was less the decision of the director as the president. This is one reason why Putin was contemplating putting someone like Kochnev or another FSO veteran, governor of Tula Alexei Dyumin, into the position. They lack the experience and, unkind souls might say, the wit for the role, but no one would question their loyalty to Putin or their willingness to do whatever it takes to reserve the regime.

Yet arguably here is Putin’s blindspot. On the face of it Korolev seems the perfect candidate: relatively young, undeniably sharp, experienced, well-connected, and as merciless as anyone might want in their new guard dog. As far as Putin is concerned, he does not seem to see corruption, or close ties to figures in both the underworld and ‘upperworld’ elite (Korolev has been linked both with the Rotenbergs and possibly also Sechin), as a problem.

Putin does not seem to see corruption, or close ties to figures in the underworld and ‘upperworld’ elite as a problem

They are, though. It is precisely these incestuous connections between economic and coercive power – witness ‘Sechin’s Spetsnaz’ and the framing of Economy Minister Alexei Ulyukaev – which has led to the current crisis. They are the basis for the industrial-scale embezzlement that undermines the economy and the ‘raiding’ that makes a mockery of technocratic efforts to encourage investment and innovation. They preserve the corruption at every level of the system, especially when carried out by the very agencies meant to police it, that has given Navalny’s message such resonance. And ultimately, they are loyal only to themselves. One has to wonder whether, in a crisis, they would choose to defend Putin to the end.

How many emperors, after all, ultimately found themselves bidding for the loyalties of their Praetorians, and realised that loyalty bought with gold and indulgence is no loyalty at all?