In March the French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen (FN) visited the Duma in Moscow, looking for financial support for her presidential campaign. A month earlier a delegation of the far right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) headed by its leader Frauke Petry traveled to Moscow seeking cooperation with Russian politicians. Why do they and other far right European parties turn to Russia for financing and support? And what is Russia’s policy vis-à-vis the European far right? Researcher Anton Shekhovtsov sheds light on the ties between Russia and the radical right in Europe.

Vladimir Zhirinovsky, leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, was one of the first far right politicians in Russia who tried to build a far right international. The first Congress of Patriottic Parties, that is to say, far right parties, took place in Moscow in 2003. The French Front National was invited, and other far right organisations, but also a number of pro-Russian organisations from Asia and even Africa. At that time Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was under sanctions. Saddam Hussein paid a lot of money to far right forces in the West so they could lobby for removal of the sanctions.

I think many far right politicians actually tricked Saddam Hussein. They did lobby, of course, but their influence was minimal. After the occupation of Iraq some documents were found, that showed that for example two leading politicians of the FPÖ, the Freedom Party of Austria, received 5 million dollars. Jean-Marie le Pen, then leader of the Front National was lobbying for Iraq since the nineties. It’s unknown how much money he received, but probably there was some money involved as well.

Honeymoon and moneylaundering

At that time only the fringe figures of Russian politics were interested in cooperating with the far right in the West. Why did it change? It changed in 2004-2005. Russia had a honeymoon with the West during the first presidential term of Vladimir Putin, from 2000 to 2004. The ruling elites in Russia were quite happy to launder money in the West, to cooperate with big businesses etcetera, etcetera. Moreover, Western politicians were quite happy to cooperate with Putin.

You may remember that US president George Bush remarked that he got ‘a sense of Putin’s soul’ and found him ‘very straighforward and trustworthy’. At a meeting in 2002 Western leaders praised democratic reforms in Putin’s Russia. Within Russia’s ruling elites it created the feeling that the West uses only rhetoric, that liberal democracy are only words, that actually it is the same as with us. Democracy and human rights are a kind of cover for their own corruption. The Russian elite thought: ‘We know we are corrupt. We cooperate with them, so it means that they are corrupt as well.’

Colour revolutions

But all that began to change in 2004. The turning point was a series of colour revolutions in post-Soviet space. First Georgia, then the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and in 2005 in Kyrgyzstan. In Moscow these colour revolutions were considered Western, or US inspired, attempts to bring about a colour revolution in Russia itself. The ruling elites in Russia saw this as breaking the contract between mainstream politicians in the West and Russia. This is the defining moment when the officials, the media and youth organisations in Russia switched to anti-Western and anti-American sentiments.

Rose revolution in Georgia, 2003. Photo Wikimedia

Rose revolution in Georgia, 2003. Photo Wikimedia

The Russian ultra-nationalists, who already in the nineties were anti-American and anti-Western, left the fringes and became more mainstream in Russian socio-political life. Russia’s turn against America, the challenge towards the EU that Russia might become, the Kremlin’s appeal to traditional values, its conservative posture, Putin’s populist language about the rights of the majority, about national identity, about the divide between the elites that promote multiculturalism and the ordinary people – all this caught the attention of the far right. They concluded: Putin’s Russia is our ally.

From fringe to alternative

Since the end of World War II the far right was marginal in Western European societies. They tried to modernize their ideology, but they lingered on the fringes. Turning to Putin’s Russia they could now claim: we’re no longer marginal. Look at Russia, it’s a huge country, a geopolitical power, driven by the same ideas that we have. This had a huge psychological effect. Moscow doesn’t have to sponsor all the far right parties in the West. Many promote Russia-friendly ideas for free. They feel: we’re not on the fringes anymore. We are an alternative mainstream, we are a new mainstream and we are going to take power across Europe and the West.

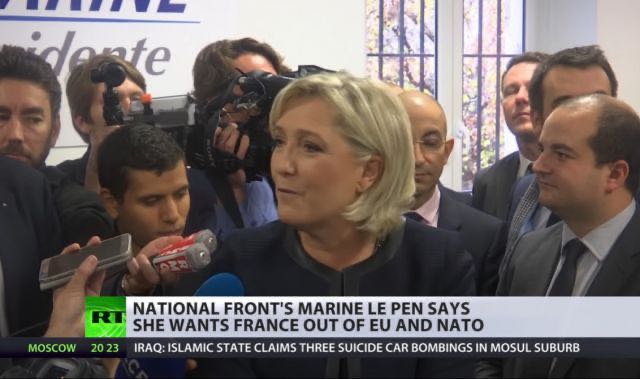

Marine le Pen on RT. Photo: screenshot RT

Marine le Pen on RT. Photo: screenshot RT

Creating ambiguity

These developments materialised in two institutionalised forms of cooperation: electoral monitoring and media. Putin’s regime indeed feared a colour revolution in Russia itself. That threat was largely virtual, a colour revolution was never on the table in Russia in 2004, 2005. Many politicians close to Putin’s regime understood that electoral monitoring, especially by the European security organisation OSCE, could play a very important role in mobilising people in order to reject fraudulent elections. The colour revolutions, I want to remind you, were not revolutions but very successful protests against electoral fraud. How do you know that elections are fraudulent? You can always refer to esteemed monitoring organisations, such as the OSCE. So in order to counter this danger, Russian politicians created their own monitoring organisations.

They invited far right politicans, from Russia itself and far-right and far-left politicians from the West. In March 2014 during the referendum in Crimea we saw these same far-right and far-left Western activist as observers. Ofcourse the results of their observations were never taken seriously by the OSCE or the UN. But they managed to create this façade of independent electoral observation. For domestic audiences in Russia they could be presented as legitimate observers. It creates ambiguity. There is one point of view, the one of the EU or OSCE, but there is also a contrasting point of view.

The West is bad

The engagement of the state controlled Russian media with the far right started in 2008. In August 2008 Russia provoked Georgia into a war. Russia managed to occupy Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The ruling elites in Russia understood that it was easy to win a war, but they lost the information war. They had tv channels like Russia Today and the Voice of Russia, but they truly felt that the Kremlin’s soft power was failing. In 2009 Russia Today was renamed into RT to conceal the obvious link with the Russian state. If previously they promoted the idea that Russia is good – which is soft power – a new idea was added: that the West is bad.

Ideologically the cooperation is driven by anti-Americanism, anti-liberalism and anti-multiculturalism. It developed from an attempt to legitimize Russia’s foreign policy. Increasingly it became a factor of destabilization of Western unity.

It was important to present to Western audiences the point of view of Westerners themselves. Who do you invite to tell that the West is bad? The far right. Isolationists, conspiracy theorists, some parts from the far left milieu. Many of the people who were invited by RT and other Russian media came from previous contacts of the Russian ultra-nationalists. For example: Manuel Ochsenreiter, who is a German neo-fascist, editor of a journal called Zuerst; Lyndon LaRouche, American political activist, with obvious fascist affiliations;

Geert Wilders for several weeks was asked for comments on Trumps victory. On Russian tv they are labeled right wing or conservatives, never far right. Their affiliations are never mentioned.

Kremlin’s attitude is flexible

The Kremlin always welcomed pro-Russian activities, but they always look at the national context, whether they can cooperate with the far right in any particular country. For instance: Putin’s Russia was quite happy to cooperate with the social-democrats and the conservatives in Austria, because these are the parties that have good ties with the largest businesses and financial institutions, which could be beneficial for the Russian ruling elites. Cooperating with the Austrian Freedom Party, FPÖ, the major opposition party, would compromise Russia’s links with the social-democrats and conservatives.

But in 2016 something changed. In the first round of the presidential elections in Austria no representatives of these mainstream parties won. The two candidates in the second round were FPÖ-leader Norbert Hofer and the independent candidate Alexander van der Bellen. This gave the feeling that Putin’s allies in Austria were in decline. It created the opportunity that the Kremlin could support the FPÖ. In November 2016, before the rerun of the elections, the ruling Russian party United Russia decided to conclude a cooperation agreement with the FPÖ. I’m sure that it was the initiative of the FPÖ, that asked for such an agreement years before. It opens many possibilities for the FPÖ. In December not Hofer, but Van der Bellen won the elections. Now the aim of the Kremlin is 2018, the parliamentary elections in Austria. The FPÖ is the most popular party in Austria and Moscow hopes the party will rule.

Another example is the French Front National. Marine le Pen was in 2011 elected as partyleader. She immediately said that she wanted to go to Russia and get in touch with people in power. The Kremlin didn’t offer high level officials, because of the upcoming elections in France in 2012. Moscow didn’t want to spoil its relations with either Sarkozy or Hollande. When Hollande was chosen, Putin met him and Hollande ostracized him for his support to Assad in Syria. Then the advisers of Putin concluded: this is not working. Let’s support the Front National. That’s how it started. The FN received an 11 million euro loan from a Russian bank.

Plan A of Kremlin’s politicians is: we cooperate with mainstream politicians of an European country. If it doesn’t work, we have plan B and will cooperate with far right parties and make life difficult for the mainstream parties that refuse cooperation. The Kremlin may also return from plan B to plan A. Moscow doesnot want to compromise its relations with the French presidential candidate Fillon, who has a Moscow-friendly attitude, by supporting Le Pen. This is why the Front National got into problems with the loan.

This is an short version of Anton Shekhovtsov's lecture at the Institute of Human Sciences (IWM), Vienna, held on January 25, 2017