With the end of the Cold War the geo-strategic reality in Europe changed. The Charter of Paris, signed in 1990, confirmed the right of both small and large states to decide their own destiny. Annexing Crimea and claiming spheres of influence, Russia acts against the post-Cold War principles. The European response, pleads German social democrat Karsten Voigt, should be measured: cooperation, as far as possible, and a defensive security policy, as far as necessary.

For a large part of their history, the destiny of the peoples living in Europe has been shaped by the interests of the great powers. For centuries the Russian, Ottoman and Habsburg empires and France and Britain have dominated the European continent. Since the 19th century until the end of World War II first Prussia and then Germany, indirectly and directly, joined this competition for influence. After the First World War in Versailles and after the Second World War in Yalta the big powers of that time shaped the European political landscape for decades.

Division of spheres of influence at the Vienna Congress, 1815

Division of spheres of influence at the Vienna Congress, 1815

This centuries-old experience of being the object of competition between the big powers and not a sovereign subject of one’s own making continues to influence political debates in Europe to this day. Of course, the historical memories of former threats and domination are stronger in smaller states than in larger ones. One reason for this mind-set is that larger states possess more abilities to influence their own conditions than smaller ones. This is still a reality of international politics. Yet a reliable and sustainable order in Europe can only be achieved if states, both large and small, are prepared to establish a fair balance of interests and influence.

Accordingly, the complex voting rules in the European Council and in the European Parliament are a typical expression of the desire to define this fair balance between smaller and bigger countries. Beyond these formal voting rules the European Union is based on the guiding principles of a common political culture, chief among these the ideas of co-dependence and integration. If the largest state in Europe, Russia, first in Georgia, then in Crimea and now in Eastern Ukraine is returning to the logic of the “concert of big powers” this affects not only the direct neighbours of that power but undermines the stability in Europe as a whole.

Small states

With the initiation of the Helsinki Process, the equality of smaller and bigger states has been demonstrably strengthened. The Charter of Paris, signed in 1990, confirmed the right of both small and large states to decide their own destinies. Therefore, when Russia acts against the principles of the Charter, and annexes part of the territory of a neighbouring state, supports the use of military force in other parts of a smaller state, and claims the right of specific zones of influence, then such a policy is an attack on the basic principles, norms, and values that formed the basis of the post-Cold War political order.

If we accept such behaviour, then Europe as a whole will soon be dominated again by the old ghosts of mistrust and conflict. As such, it is not anti-Russian sentiment but a commitment to the principles, norms, and values of a peaceful European order that has guided the German government during the Ukrainian crisis. Russia has not withdrawn the signature of the Soviet Union from the Paris Charta. When it is violating the agreement that does not mean that the values and norms of the Charta are rendered invalid.

In the years after the peaceful fall of the Berlin Wall and the largely peaceful end of the Soviet Union our policy towards Russia was defined by the desire to combine the process of integration with cooperation. In the wake of the Ukrainian crisis, however, the coming years – though hopefully not decades - will be defined by a cooperation, as far as is possible and a defensive security policy, as far as is necessary.

In November 1990 Bush, Gorbachev, Thatcher, Kohl, Mitterrand and heads of state of smaller countries signed the Charter of Paris. Photo Bush Liberary

In November 1990 Bush, Gorbachev, Thatcher, Kohl, Mitterrand and heads of state of smaller countries signed the Charter of Paris. Photo Bush Liberary

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, pan-European cooperation deepened and accelerated. The Charter of Paris defined the common principles of Europe, whole and free. Russia was included in the Council of Europe and became a partner of the EU and NATO. Trade and cultural exchanges increased, and the network of pan-European relations became denser. While the objective of a full membership of Russia in the EU and NATO was perhaps never realistic, the West tried, though not consistently enough, to achieve closer cooperation at least. The security relationship between Russia and the West - and especially Russia and the USA - was dominated by the effort to enlarge the areas of cooperative security and to diminish the importance of the concept of mutual deterrence.

Putin regards the collapse of the Soviet Union not as a historic opportunity for building a modern and democratic Russia

Russia aspires to be a world power

But the Russian leadership has since then changed its view on Russia’s role in its neighbourhood and in the world at large. President Putin regards the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of Soviet Communism not as a historic opportunity for building a prosperous, modern and democratic Russia but 'as the greatest geo-strategic disaster of modern times'. Putin's Russia does not want to be recognised internationally as a great Euro-Asian power, but as what it once was: as a world power, equal to the US, in its hard power arsenal especially. But to be strong militarily and weak economically is the long run not a stable foundation for a country aspiring to be a world power: on the contrary. Such a policy is provoking negative reactions: The attempt to maintain and recover zones of influence is perceived by Russia as its historic right but to most of its neighbours it is seen as Russian revisionism and irredentism.

Russia failed to build up mutual trust and cooperation with its smaller western neighbours after the Cold War. This failure is not only the result of Russian mistakes. Russia meanwhile sees US policy as the most relevant factor in the souring of post-Cold War relations. Russia´s hope, that this negative trend might be reversed after the election of President Trump has faded away. My own view is that it is the mostly negative and deteriorating relationship between Russia and its smaller western neighbours that is the most important foreign policy reason for the increasing alienation between Russia and the members of the EU and NATO.

At the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, the Congress of Berlin in 1878 and at the Conference in Yalta in 1945, the destinies and the boundaries of Russia’s western neighbours were decided by Russia and the western powers of the time. This geo-strategic reality changed with the end of the Cold War. Already during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, it was obvious to me that leading actors especially in Yugoslavia, but also in Russia did not understand the new European realities after the end of the Cold War. When I met, as president of the Parliamentary Assembly of NATO, with leading politicians in Belgrade at the time, they obviously had difficulties understanding the consequences of the fact that for the US, Britain, France and Germany it was more important to harmonise their views than to follow their traditional different national strategies.

Common European values

Since the 1990s we have a geo-strategic constellation which is different from all previous centuries: all European nations have signed up to the goal of a common democratic system of values as defined by the Council of Europe. Most of Russia’s western neighbours are now members of the EU and/or of NATO. Britain, France, and Germany will - like other countries in Europe - beyond their policies as members of the EU and NATO pursue also individual bilateral policies with Russia. As the debate about Nord-Stream 2 is showing, Germany´s eastern neighbours cannnot exert a veto-right on Germany's Russia-policy. But Germany's Russia-policy will not be pursued behind the back of smaller European states and without taking their interests into consideration. For Germany, Russia is the most important country east of the boundaries of the EU and NATO. But it is not more important than our relationships with our partners in the EU and NATO.

Clearly after 1945 the USA and the Soviet Union were the key determinants of European security. Their impact was often also decisive for societal developments inside their respective spheres of influence. I am not underestimating the role of the US and Russia in Europe today. But their role - and especially the role of Russia - has changed enormously. It cannot be compared to their role during the Cold War or during the period of detente. Russia no longer decides which governments are formed in East-Central or South-eastern Europe. And no Russian government exerts a veto-right over the foreign policy of East-Central and South-eastern European countries. Unlike in the 19th century Western Europe’s powers are integrated into the EU and NATO. This integration has fundamentally changed the geo-strategic framework for their policies towards Russia and - in a different way - towards South-eastern Europe and the Western Balkans as well.

Not only moral reasons

Russia seems to underestimate the importance of these changes, the historical significance of this new European security landscape. The present Russian leadership prefers a return to a concert of big powers, in which they can carve out a sphere of influence and from there apply rules and norms which differ from the accepted international norms and the principals of the Charter of Paris. It is not only for moral reasons but also geo-strategic ones that the preservation of the European order requires a new approach—one that cannot be based on the ideological convictions of previous diplomats, like Metternich, Bismarck, or Kissinger.

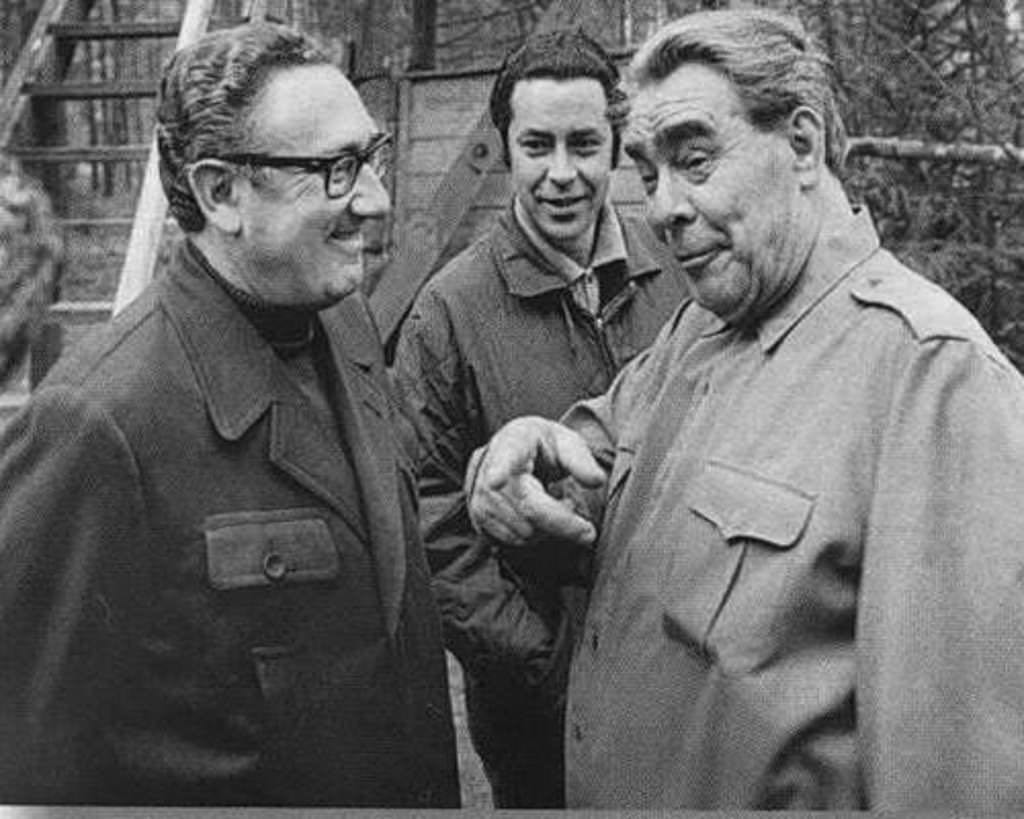

Henry Kissinger with Russian leader Leonid Brezhnev at hunting lodge near Moscow, 1973

Henry Kissinger with Russian leader Leonid Brezhnev at hunting lodge near Moscow, 1973

There are analysts and politicians who argue that the European order does not need to be based on the norms, rules, and values on which we agreed in the Charter of Paris and in the Council of Europe. Yes, it is true: even in absence of such a common basis many compromises and pragmatic agreements with Russia are possible and desirable. The willingness to continue cooperation with Russia, whenever possible and reasonable, is the expression of our realism. But without a basis of common norms, rules, and values we will always be far away from a truly stable European order and peace.

In the next years, we therefore need to protect the stability and security of those parts of Europe which are based on common norms, principles, and values as defined in the Charter of Paris and in the Council of Europe. At the same time, and in a very pragmatic way, we should - where ever possible - cooperate with those European nations, which means in practice especially with Russia, who challenge these principles and values and who thereby directly or indirectly are also undermining the cohesion, stability, and security of the European order and key institutions like the Council of Europe, the EU, and NATO.

Understand, not agree

We should continue pursuing an active dialogue with the Russian leadership and - so far as this is still possible - with the Russian society. To strive for cooperative solutions does not mean to underestimate meaningful conflicts of interests and values. To try to understand Russian policies does not necessarily mean to agree with them either. Especially during a crisis, intensive communication is an indispensable prerequisite to the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

On the other hand, unlike in previous years, we have to accept that the EU and NATO have to take precautions whenever Russian policies pose risks and dangers for Russia’s neighbours, for the members of the EU or NATO, or for European security as a whole. Nor can we accept that boundaries are changed by force and that political and military steps in contradiction of the Charter of Paris are legitimised by any European country, especially not by the EU and NATO. The Russian involvement in the military conflicts in Georgia and Ukraine has led to a revival of NATO and the importance of collective defence. I doubt whether this was intended by the political leadership in Moscow.

Blue Helmets

But the war in Eastern Ukraine has also shown that we need to strengthen the OSCE and other instruments of cooperative security. We need to examine whether OSCE “Blue Helmets” can be deployed in Eastern Ukraine. Whether all members of the OSCE and especially the Russian leadership are ready for an improvement of the existing rules and greater transparency in arms control should also be explored. This could mean that other elements of cooperative security, like confidence-building instruments, and agreements which enhance the transparency of military decisions, are strengthened, and this in an environment which during the last years has been dominated by mistrust and conflict. The NATO-Russia Council should be activated with the goal to enhance the strategic stability in Europe.

OSCE monitoring the movement of heavy weaponry in East Ukraine. Photo Wikimedia

OSCE monitoring the movement of heavy weaponry in East Ukraine. Photo Wikimedia

Many are talking of a new Cold War. Others are expressing their desire to return to the cooperative approach practiced during the period of detente. Both are, to various extents, understandable positions. It would be best of all, however, if we could develop concepts which are appropriate for today's challenges.

It takes two to tango

On the one hand, the conflict in the Eastern Ukraine is a “hot” war. On the other hand, we are - in contrast to the Cold War - at least on paper - united with Russia by common principles; a commitment to a policy of peaceful resolution of conflicts.. We should not too quickly put the institutions, contacts, and norms on which we agreed in the last decades at risk. If Russia, however, were to undermine this network of relationships, we cannot repair the damage unilaterally.

Our future relationship with Russia can develop in different directions. There are alternatives. We should always support policies that tend towards a more cooperative and peaceful direction. Whether such policies are realistic, however, will primarily be decided in Moscow. After all, a policy of cooperation needs at least two for it to have legs.

See also our articles by Hannes Adomeit and Lilia Shevtsova on the spoiled German-Russian relations