27-year-old journalist Viktoria Roshchyna died in Russian captivity shortly before she was going to be exchanged in a prisoner swap. Russian authorities claim that this happened during her transfer from Taganrog to Moscow, but Ukraine is investigating Roschyna's death as murder and a war crime. Hromadske journalists Viktoria Beha and Khrystyna Kotsira reflect on their former colleague's work.

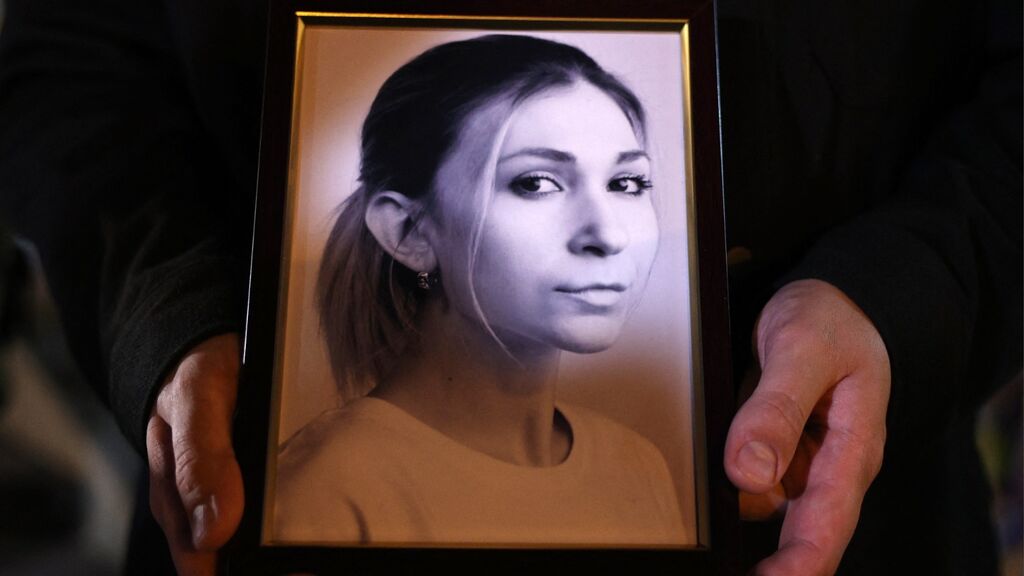

Portrait of Viktoria Roshchyna at a memorial honoring fallen Ukrainians. Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / AFP / ANP

Portrait of Viktoria Roshchyna at a memorial honoring fallen Ukrainians. Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / AFP / ANP

By Viktoria Beha and Khrystyna Kotsira

Viktoria Roschyna worked for Hromadske for more than five years. She was one of those journalists who do not wait for an editorial assignment. As soon as something was happening, Viktoria was already there. At rallies, skirmishes, sites of murders. She took on the most difficult challenges, loved law enforcement topics, attended high-profile and important court sessions. Time and geography were unimportant to her - at any moment, Viktoria was ready to go on a business trip even before she was told to go. She had no days off, holidays, or sick leave.

From 2017 to 2022, Viktoria conducted dozens of livestreams on hromadske - from outside government buildings and courtrooms, meeting national guardsman Vitaliy Markiv and political prisoners Oleg Sentsov and Oleksandr Kolchenko live on the air as they were released from captivity, shooting films and writing articles on various topics.

On February 23, 2022, Viktoria was in Shchastia, Luhansk Oblast. She went there on the eve of the full-scale invasion, because she understood that something was about to happen, so she travelled closer to the front line.

With the beginning of a full-scale war, Viktoria filmed videos and wrote articles from hot spots in the east and south of Ukraine. In the first two weeks, she managed to make a report from Hulyaipole, which was under constant fire at that time, and from Zaporizhzhia, which the Russians were approaching; to talk with the evacuated residents of Volnovakha and tell the world how the temporarily occupied Enerhodar lives.

Then Viktoria prepared pieces about the military operations in the Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk oblasts and planned to go to Mariupol to report what was really happening in the city, which was already encircled.

On March 16, 2022, we learned that she was detained by the Russians on the way to Mariupol and imprisoned in the colony of temporarily occupied Berdyansk. On March 21, she was released. Viktoria wrote the column 'A week in the captivity of the occupiers. How I got out of the hands of the FSB, Kadyrovites and Dagestanis' about that experience. Immediately after her release, Viktoria still made a story about Mariupol, talking to the evacuated residents who were in Berdyansk at that time.

Later, she started working as a freelancer for various newsrooms in order to have more freedom in where she goes and what she covers. She visited the occupied territories and wrote reports from there.

On August 3, 2023, Vika went missing in the temporarily occupied territories. Only in May 2024, Russia confirmed for the first time that it was holding her captive.

On October 10, her death was reported. Petro Yatsenko, the spokesman of the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, said that Viktoria was being prepared for exchange, but 'unfortunately, we failed to do it in time': 'The fact that she was being transferred from Taganrog to Moscow was the stage of her preparation for release'.

We were really looking forward to the day of Viktoria's release. But there will be neither a livestream nor a happy return story.

However, hundreds of her articles remain. They meant a lot to her. They were her life and a part of her.

Film about juvenile detention centers

Shortly before the start of the full-scale war, in January 2022, Viktoria presented a film about juvenile detention centers.

In it, she explored how staying in such institutions affects young men. She communicated with convicted teenagers, those awaiting sentencing, and those who committed a repeat crime, as well as with prison colony workers, volunteers, and psychologists.

In addition, Viktoria worked on stories about a boy who was sentenced to six years for selling several grams of cannabis, and a teenager who was accused of attacking relatives with a knife.

PTSD

In 2021, Viktoria made a film about how to psychologically return the military from the war, what (and is it enough) the state does for this. In the film, she told the stories of Oleksiy Belko, who 'mined' the Kyiv bridge, Dmytro Balabukh, who stabbed a person at a bus stop, and Mykola Mykytenko, who set himself on fire on Independence Square in Kyiv. Viktoria tried to give an answer to the question of why soldiers return from war physically, but psychologically they fail to do so. Why is the war still with them?

Viktoria was the first journalist to deal with the history of a children’s home in Mykolaiv Oblast, where in 2021 one of the underage students was allegedly forced to have an abortion. Then the law enforcement officers opened a criminal case, the girl was sent to rehabilitation, and politicians and representatives of the children's commissioner took the situation under their personal control.

However, the story did not end there. For many alumni and former employees of the children’s home, it became an occasion to openly talk about their pain. Most of the alumni, in conversation with Viktoria, compared this place to a prison: few people know what happens behind the closed doors of the children’s home, so it is difficult even for the relevant authorities to control it.

Maidan

From the beginning to the end of her work at Hromadske, Viktoria did not leave the topic of the shootings on Maidan [during the 2013-2014 Revolution of Dignity]. She wrote articles about the 'Black Company' of the Berkut riot police, the kidnapping and torture of Maidan protesters Ihor Lutsenko and Yuriy Verbytskyi, as well as key verdicts in the Maidan legal cases.

All articles of Viktoria Roshchyna for Hromadske are available at this link.

This article was originally published on the website of Hromadske.