We are the most educated and globally competitive young generation that Eastern Europe has ever seen, writes Ukrainian journalist Maxim Eristavi, co-founder of tv-station Hromadske International in Kiev. Still our countries fail to give us opportunities in business and politics. Power is heavily concentrated around a small group of oligarchs and their kleptocratic political proxies. Young people are hungry for change, but don't see it coming fast enough. That’s why many vote with their feet.

Eastern Europe is a region of vibrant young energy trumped by growing demographic crisis.

Leaving your country is something almost all young people in Eastern Europe consider at least once in their lives. Coming from Ukraine, I was one of them. I left, but I came back. Still, my country makes it so hard for people like me to stay.

If you are younger than 35 and from Belarus, Moldova, Latvia, Russia, Ukraine or Georgia, emigration is an ever present thought. It is nothing new: it runs in families. Forced mobility is part of our cultural DNA.

Our grandparents were pushed out of their homes by the devastating historical cataclysms of the 20th century: whether by the Second World War that saw tens of millions displaced and turned Eastern Europe into a scorched and blood-soaked land; or by ruthless totalitarian rulers, who, like Stalin in the case of the Crimean Tatars, during the war deported complete ethnic groups, falsely accused of treason, thousands of miles away; or by genocidal design, like in the case of the artificially created Ukrainian famine of the 1930s, the Holodomor. Victims of the war, hunger or political persecutions, my grandparents moved around Eastern Europe a lot before settling in Eastern Ukraine. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union another displacing force hit our homes – poverty.

During the harsh 1990s Ukraine alone lost more than half of its economic output, with hyperinflation running as high as 10,000% in 1994. Millions went on a scavenger hunt abroad, often ending up in the claws of modern slavery. Still, they were considered as the lucky ones by those who stayed behind. Up until now, their remittances keep Eastern European economies afloat, reaching numbers as high as 23% of GDP in Moldova, 14% in Armenia and around 7% in Ukraine. In these years my father would drive his truck over the border to Russia through gang-controlled roads, often negotiating his life with local mafia, in order to earn $100 a month and protect his family from starvation.

Marry a foreigner

After all of this, would you blame Eastern European parents for raising their kids with the idea that getting a good job abroad or marrying a foreigner is the perfect goal in life? My mom would often ‘advise’ me to find a foreign husband. In my country that is the equivalent of wishing your kids the best. The mail order bride industry still thrives in countries like Russia, Moldova and Ukraine.

In a rare study about that business, an American researcher interviewed young Ukrainian women in provinces with high recruitment rates by marriage agencies and found out that two thirds of them would like to go aboard.

There’s also a tragic gap in my region between what young people can offer to their countries and what their countries can offer to them in return. If you travel to Kiev or Moscow or Tbilisi, a regular person younger than 35 there most likely speaks a decent English and is well educated, often abroad, through exchange programs or free scholarships. But in Eastern Europe the demographic crisis works against us. In countries like Russia and Ukraine, accelerating depopulation has reached staggering proportions. In Ukraine, for example, the population has diminished since 1991, downsizing from 52 million in the early 1990s to 42 million in 2015.

Every third youngster is unemployed

But less competition doesn’t bring more work opportunities. The negative spiral of a decrease of population leads to falling productivity and a decreasing number of good jobs. Eastern European countries grow older very fast, which also means that people stick to their jobs and trump career possibilities for the younger generation. For example, the average unemployment rate in Ukraine was 9% in 2015, but 25% for people aged between 15 and 24 – one of the highest rates in Europe. In Russia almost every third unemployed is a person aged between 14 and 29. More than one third of young Georgians aged 15-29 are also out of work, 60% depend on temporary employment.

We are the most educated and globally competitive young generation that this part of the world has ever seen. Still our countries fail to offer us opportunities in business, where power is heavily concentrated around a handful of oligarchs and their kleptocratic political proxies, all older than 45.

Even those who are lucky enough to have jobs, are not rewarded sufficiently. The average monthly income in post-Soviet Eastern Europe ranges between 160 EUR in Ukraine and 400 EUR in Russia. This is especially depressing for local young people, that have lots of friends in the developed world and so can compare incomes.

I am finishing my Politics and International Relations degree at one of the most prestigious universities in England, paid by working hard abroad for years. I have 14 years of work experience in media, 5 years as a contributor to the world’s leading news outlets and 3 years as a prominent advocate for civil rights, I co-founded a newsroom myself. Still the best job offers in Ukraine usually pay 15-20 times less than a low-entry salary in the States or in the EU. Being an agent of change in Ukraine is still a very costly philanthropy for young and educated Ukrainians like me.

Corruption and red tape

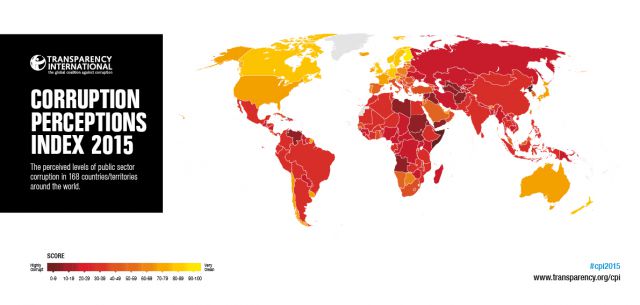

Most countries in Eastern Europe make it very hard to start your own business as well. Corruption, extensive taxation and red tape are still endemic. It is not that the procedures for launching your own company are so complicated. Actually, Eastern Europe is a global leader in cutting down regulations for new businesses, placing itself among the first league at the Doing Business ranking (Armenia and Georgia are in the top ten with Belarus being not far behind.) It is what happens after you start your own business in those countries that actually kills your entrepreneurial spirit. Apart from Georgia, all the other Eastern European countries are at the bottom of corruption indexes and are often described as classic examples of 'captured states'.

Ukraine is in the middle of an unprecedented reform drive and, under the watchful eye of a powerful civil society and international partners, has done a lot in recent years to fight corruption and deregulate the economy. Still, with more than two decades of zero reforms and so many local political elites fighting back against changes, it will take years for Ukraine to cement sustainable progress.

Brain drain

So many of my young brothers and sisters all across the region vote by feet. I myself was living abroad for years. Armenia is in the direst condition: on the day of independence in 1991 the country had a population of 3.5 million, now it is less than 2.5 million. 3 million people left Russia in the decade from 2005 to 2015. More than a million Ukrainians work abroad at the moment, and approximately 3 million more plan to look for a job abroad in the nearest future. Most brutal is the intellectual brain drain.

Look at the number of scientific publications in Ukraine, for example: in 1992 it was one of the leaders in the group of countries similar in population and economic development. Now it falls behind all of them. Russia witnesses the same level of academic stagnation. All the brightest Ukrainian, Georgian or Russian academic minds I know are based abroad, many of them at world’s leading universities, like Harvard, Yale, UC Berkeley or Queen Mary.

Brilliant reformists

Despite all of this, young people in Eastern Europe still don't desert their countries easily.

Last remaining islands of free thinking in Russia, like independent TV channel Rain or civil society initiatives like Open Russia are run by people younger than 35-40. Most of the brilliant reformists in Georgia, the most shining example of post-communist reforms apart from the Baltics, are barely in their early 30s. The average age of ministers in Georgia's first post-revolutionary governments in mid-2000s was 32. Electric Yerevan, the recent civil society uprising in Armenia was led by disenfranchised youth as well.

The biggest example of vibrant young energy is post-revolutionary Ukraine, though. It is experiencing an unprecedented creative renaissance in arts, music, IT and sports, all the sectors that are free of the toxic legacy of corruption, totalitarian mentality. They are full of young minds. Visit any office of the hundreds of local civil society initiatives that sprung up after Euromaydan: they have a strikingly young face.

One of those places, Hromadske, the region’s biggest independent newsroom (where I co-founded the international broadcasting operations) is buzzing with brave reporting talents, the majority of them are in their mid 20s. The country’s biggest independent news website, Ukrainska Pravda is headed by 29-year old Sevgil Musaeva.

A constellation of young Ukrainian reformists is well-known abroad as well: from restless anti-corruption crusader and member of the parliament Serhiy Leshchenko (aged 36), his colleague Svitlana Zalishchuk, who notwithstanding her 33 years is considered the founding mother of Ukrainian civil society, to Yulia Marushevska (27), who is dismantling the country’s most corrupt customs system in Southern Ukraine.

But behind those high-profile faces, there are hundreds of thousands of young Ukrainians hungry for changes and jobs. The Russian invasion in the Eastern Ukraine and the occupation of Crimea brought an unexpected migration boost to the country. The Russian-backed insurgency affected Ukraine’s most urban and industrially advanced regions. The Eastern Ukrainian war, followed by repression of civil society and massive wartime pillage in the socalled People's Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk forced the brightest, the youngest to flee, older and less economically active people stayed behind. Therefore, the majority of those two million internally displaced people from Eastern Ukraine and Crimea are young, educated and eager to rebuild their lives from a scratch.

Refugees-entrepreneurs

With the government offering almost zero assistance, many of them rely on their wit and talents, create job opportunities themselves by setting up small businesses all across the country. Some of those refugee-entrepreneurs have made international headlines.

Refugees-entrepreneurs in Kiev. Hromadske tv

Every day I work shoulder to shoulder with bright and young Ukrainians forced out of Crimea or Eastern Ukraine by the Russian invasion. Some of them lost everything fleeing the war, some have still close ones trapped across the frontline. Where in their position many others would succumb to depression, they keep muddling through with astonishing energy. Thanks to this influx of internally displaced people, many Ukrainian cities developed dense clusters of young and entrepreneurial creativity. My favourite example is Maria Kulikovska, a young Crimean artist who made a globally-hailed art out of her tragedy.

Maria Kulikovska, 'Sanctuary'

Maria Kulikovska, 'Sanctuary'

Still, lack of opportunities and the above mentioned demographic crisis make it harder and harder for young agents of change to operate in Eastern Europe. Almost all of my young friends, who were heavily involved in the building of new Ukraine, either left or would like to leave the country for better job offers after their savings burned up. Internationally recognized artists, like Maria, spend more time abroad now where their art is financially appreciated. Just days ago the country learnt that Marina Zanevskaya, one of the leading tennis players in Ukraine (23), took Belgium citizenship. I won’t even mention that almost all queer Ukrainians I know definitely think about leaving the country that, despite recent modest progress, still does not recognize any basic rights for them.

In 2013 I decided to ignore all the hurdles and come back to Ukraine. The desire to be part of the pivotal change was stronger than financial and career concerns. Three years later, I’m still a firm believer I made the right decision, although I have to divide my time between Kiev, Prague and London projects just to stay financially afloat. Nevertheless, I’m aware that I’m lucky and don’t have to decide between bringing change to my homeland and make ends meet. Most other young Ukrainians don’t have the same luxury. I shuttle back and forth in the world, not only gathering foreign support for Eastern European progress, but from Eastern European emigrants as well. Many are, like the Ukrainians, inspired by the unprecedented opportunities in their homelands, by small victories over the old system that we win almost every day. With my Eastern European friends living abroad I often discuss if they would like to come back. And many do.

House of Cards

But sometimes it seems their homeland is not ready to welcome them back. I recall an incident during a small gathering we had with well-educated and successful Ukrainians living in London.

Kevin Spacey as source of inspiration

Kevin Spacey as source of inspiration

While browsing the social media, we hit a film where Kevin Spacey was giving a speech in front of a gathering of oligarchs in Kiev. Prominent young MPs from Ukraine took the floor and told the actor that they went into politics inspired by House of Cards. Some even would address Spacey as Frank Underwood. We laughed and rolled our eyes. One friend nodded to me: ‘Do you really think I can quit my job in the City and go back to merge with people like that?’

At first I thought it a bit patronizing, but suddenly I saw the enormous gap between the reality and opportunities of the developed world and what Eastern Europe can offer our young generation. This big gap is widening every day.