Since Alexei Navalny’s arrest upon returning to Russia on the 17th of January, supporters of the opposition leader have made their voices heard in cities around the country. Facing a wave of popular unrest, authorities have asserted their dominance over the streets, twice breaking the record for mass arrests in a single day. The penalty for defiance has been loss of livelihood or placements in education facilities for some, while others have seen the full force of the law. Over 11,000 people were detained as a result of three days of protesting, Russia’s detention centres are fully occupied.

Crowded cells in detention center Sakharovo outside of Moscow (picture Mediazona Telegram)

Crowded cells in detention center Sakharovo outside of Moscow (picture Mediazona Telegram)

by Adam Tarasewicz

When 22-year-old student Vera Inozemtseva went out into the streets in Astrakhan on January 23 to protest against the arrest of Navalny, two uniformed officers and one man in civilian clothes approached and detained her. They drove her to the local police station while refusing to tell her why she was being arrested. Her phone was confiscated and a man in plain clothes in a ‘talk’ asked her about the regional headquarters of the Fund to Fight Corruption (FBK) in Astrakhan and her personal contacts with Navalny. Also, he wanted to know why she does not support Putin.

After her husband reported her missing, the same man who abducted her drove her home in an unmarked car with tinted windows. She was ordered not to file a complaint with the prosecutor’s service. The officer gave her back her phone only after she refused to leave the car without it.

Student Vera Inozemtseva (picture personal archive)

Student Vera Inozemtseva (picture personal archive)

Having left the car, however, she was immediately detained again by three other officers, who took her back to the Police Department, and again refused to answer her questions. She discovered that her phone had been used to distribute fake posts inciting further protests on VKontakte and Facebook. Eventually she was charged with infringements against unlawful rallies or demonstrations (section 5 of article 20.2 of the Criminal Code), which carries a fine.

After attending the Navalny-protests of 2017, sparked by his film about Dmitry Medvedev’s lavish houses, Inozemtseva started working at Navalny’s regional office as an assistance coordinator and a volunteer until it was shut down in 2018. Local outlet Ast-news.ru reported that she also ran as a self-nominated opposition candidate in a 2020 city council election, failing to be elected after finishing last.

Inozemtseva decided to tell her story to reduce the chance of anyone else falling victim. She believes that police have been ordered to do all in their power to find protest organisers, even though there were no organisers in Astrakhan.

More than 11.000 detentions

According to data from ngo OVD-Info, protests on the 23rd saw a record of over 4,000 arrests, quickly surpassed by more than 5,658 arrests on the 31st. After Navalny's verdict on the 2nd of February, a further 1,463 were arrested in 10 Russian cities. In total, 4,908 cases were opened, 2,204 of them have been heard in court.

Tactics in Police Stations

Alena Kitayeva and her sister Alexandra were arrested in Moscow following the protests after Navalny’s verdict on February 2. In an interview with tv-station Dozhd she explained that she was subjected to torture and violence by Moscow police in the Donskoy district.

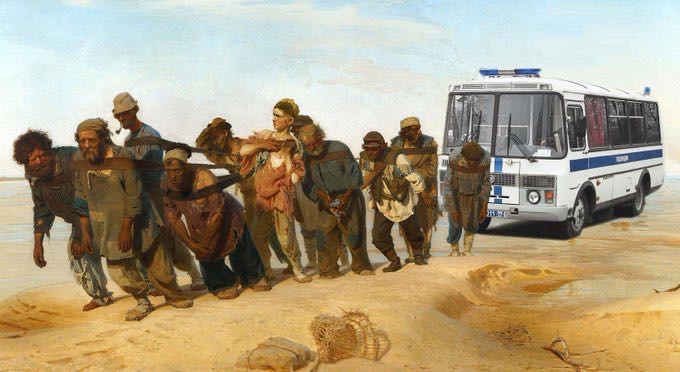

On the internet people made a mockery of Russian painter Ilya Repin's famous painting The Wolga Boatsmen: an overcrowded police van in Moscow broke down and had to be pushed by the inmates. This really happened.

On the internet people made a mockery of Russian painter Ilya Repin's famous painting The Wolga Boatsmen: an overcrowded police van in Moscow broke down and had to be pushed by the inmates. This really happened.

Alena, a volunteer at the Moscow office of FBK, and her sister were trapped in an alley by riot police and taken to the station. Officers demanded her mobile phone and fingerprinted the pair even though they had their passports with them.

When Alena refused to tell the officers her phone password, she was shut in a room with no cameras. Two Police Officers and two functionaries at the police station were present. The officers put a plastic shopping bag over her head, and she suffocated while her chair was pushed from under her.

Her cries for help were mockingly imitated by the officers, one of whom scratched his own face, insinuating that no one could prove it was not her who attacked him. When they threatened her with a stun gun, she gave her phone password and the officers went through her personal data and contacts.

In an interview given to The Insider, Alena’s sister Alexandra told how she was yelled at when asking to wait for her lawyer, and having her hand forced open by a man and a woman in order to take her fingerprints. Her hand was bruised.

When Kitayeva asked about her sister, the officers said: ‘we killed her’, and ‘she is dancing a striptease for us’. After further threats, she gave up her phone password, and the officers searched her contacts, social media, and wrote down the numbers.

Repression of the Press

During police raids tens of journalists were harassed as well. According to The Guardian, 82 journalists were arrested on the 31st alone. OVD-Info, an ngo that tracks arrests at police stations (the Russian abbreviation stands for Department of Interior Affairs), reported at least 49 journalists detained on the 23rd. Sergey Smirnov, editor-in-chief of the critical Russian news outlet Mediazona, was arrested, while walking with his little son, for inciting ‘an unlimited number’ of people to participate in protests on the 23rd.

Smirnov’s crime was retweeting a joke which featured the date of a pro-Navalny rally. As a result, he was found guilty of 'repeatedly violating rules to prevent public incidents' (part 8 of article 20.2) and given 25 days. After protests by media, colleagues and the Union of Journalists the sentence was reduced to 15 days. Smirnov was interned at the Sakharovo detention centre on the outskirts of Moscow.

Conditions in Sakharovo

Due to a lack of cells in Moscow the migration detention centre in the village of Sakharovo on the outskirts of town received at least 812 detainees. According to a BBC report Sakharovo struggled with the numbers as well. Often, police vans with new inmates are forced to queue up due to lack of space. On the 2nd of February, detainees could not be accommodated quickly enough so had to sleep in the vans, video messages detail how they were deprived of water and food and not allowed to go to the toilet.

On the outside of the detention centre, one father named Yuri organised a waiting list to help relatives bringing supplies adapt to the strict one-at-a-time system. Visitors put their name on the list and while waiting were able to keep warm in their cars, yet Nikita (89th in line), said he arrived at 8am, and was not sure if he would get his turn that day.

On the inside, inmates talk of cramped conditions, and the necessity for the rations brought by their relatives. They are given food three times a day but reports from other police stations suggest this is not the case everywhere. Ekaterina explains she was given no food or water for nearly two days until her friend filed a complaint.

Cramped conditions are noted in both women’s and men’s cells. While explained as temporary overnight arrangements, in order to stop detainees having to sleep in the police vans, pictures of Sergei Smirnov in a cell, designed for 8, but filled with 28 people, has attracted attention. Toilets are nothing more than a hole in the floor with no privacy from other inmates. Other reports have mentioned a security camera is pointed at the toilet in women’s cells.

While inmates are typically allowed their phones for 15 minutes per day, in Sakharovo they are given an old phone into which to put their own SIM. Inmates have experienced problems if they have an incompatible SIM card, do not remember their relatives’ numbers by heart, or if they were not told to keep their SIM.

Toilet facilities in a cell in Sakharovo (picture PDM news)

Toilet facilities in a cell in Sakharovo (picture PDM news)

Consequences of Protesting

Anna Wellicok, who complained about the privacy issues in women’s cells at Sakharovo, was a lecturer at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics. The School terminated her contract with a statement on university regulations prohibiting participation in illegal rallies.

She is one of many who work or study at education institutions in Russia that faced similar consequences as a result of their participation in pro-Navalny rallies. The BBC published some of their accounts.

Protesters were faced with severe consequences at their education institutions, where participation in illegal rallies spposedly has broken codes of conduct. Artem Nazarov, a teacher at the Kobzon Institute of Theatre Arts, was kicked out of school after attending the 23rd of January rally in Moscow. Similarly, Alexander Ryabchuk, Rostov-on-Don’s ‘teacher of the year’ for 2020, chose to resign after ultimatums from both schools where he worked.

Detainees in Sakharovo managed to stage a protest, shouting: Putin is a thief, freedom for Navalny!

Detainees in Sakharovo managed to stage a protest, shouting: Putin is a thief, freedom for Navalny!

Meanwhile, three students were expelled by Astrakhan State University for attending protests on the 23rd. They aim to take their expulsion to court, but the rector of the institution announced on VKontakte that students should think ‘100 times’ before attending rallies.

For young people like Feona Vardanyan, protesting even has cost them their homes. After attending a rally on the 23rd, she was told to resign from her job as a teacher at the Pyatigorsk College of Trade, Technology, and Service, according to a 'house rule' of the school that nowhere could be found. As the school provided her accommodation, she had to raise money on social networks to find new housing.

After Navalny’s sentencing, FBK announced the suspension of street protests until the spring and summer. According to Leonid Volkov, leader of FBK's regional staff, the decision was made to avoid ‘thousands’ of new arrests and use the coming months to prepare actions for the September parliamentary elections. Navalny's plan is to reactivate his tactics of ‘smart voting’ to defeat Kremlin party United Russia. Copying Belarusian grassroot activism Volkov asked people to go out into their courtyards on February 14 at 20.00 hours and light their mobile phones in a peaceful demonstration of protest.