On July 1 in a hospital in Dnipro the Ukrainian poet Victoria Amelina (1986 - 2023) succumbed to her wounds. She was one of the victims of Russia's missile attack on a well-known restaurant in Kramatorsk in the Donbas. As many writers, after the Russian invasion she started to help refugees and collect stories about Russia's war crimes. She wrote several testimonies of the war. To honour her we publish her impressive Diary of Silence.

Victoria Amelina, collecting evidence

Victoria Amelina, collecting evidence

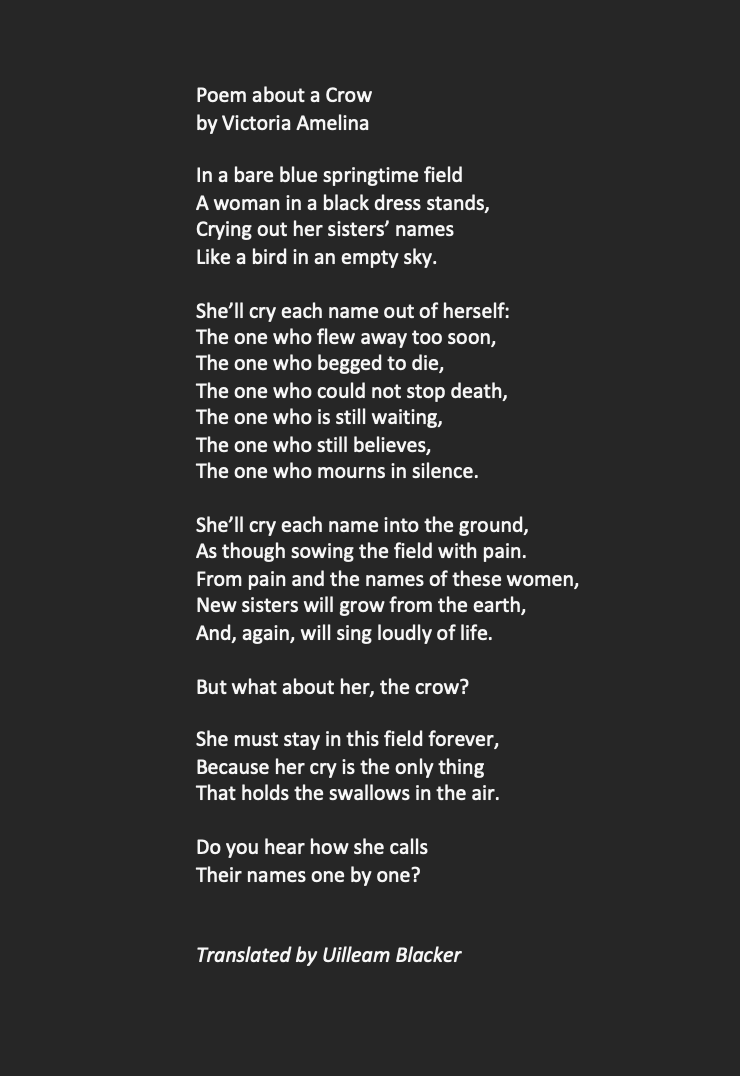

by Victoria Amelina

Eight days before the great war.

My friend from Ivano-Frankivsk and I are sitting in a Lviv coffee shop with a young girl from the Donetsk region, to whom we were showing the city.

'Can you imagine,' says my friend, 'my younger sister is being taught how to go down to the bomb shelter! In Ivano-Frankivsk! It’s madness!'

The girl from Donetsk region is silent, but I don’t let her remain so.

'Did you run for cover at school?'

'Yes, when there are three rings, then you have to run to the basement,' she answers casually. 'Because the siren is hard to hear there.'

Silence. Two days before the great war.

The Russians announce the recognition of the so-called people's republics in our Donetsk and Luhansk regions. I am finishing an application for a crowdfunding platform. In September 2022, we plan to hold our literary festival in a small town called New York, forty kilometers from Donetsk.. The application is called 'The New York Literary Festival will be!'

I write on social networks that I’ve submitted the application in spite of everything, and I receive only cheerful comments. No one writes to me anything like: 'And we have already left Kyiv for Transcarpathia' or 'And we have already crossed the border' or even 'And I'm already in Mariupol with my brothers-in-arms.' Why didn’t we shout?

The first day of the great war.

'Better keep quiet', a colleague writes to me publicly in a comment on social media. After all, I found myself abroad on the twenty-fourth; the war began two hours before my plane was supposed to take off.

I do not face the first moments of the great war together with everyone, only with dozens of Ukrainians at the airport. They are silent – maintaining their dignity, as my acquaintance would advise them. Only a woman with a child in her arms is sobbing, wondering where to take her children.

Everyone else is silent.

On the same day, I find exorbitantly expensive tickets to Prague on the Internet.

The Czech border guard looks at my passport without a word.

She remains silent as she puts in the entry stamp.

And I cannot even thank her; something is caught in my throat.

The third day of war.

I’m back in Ukraine. The colleague who demanded that I keep quiet because I was abroad apologizes to me. I don't answer her. Maybe it wasn't such a bad idea to be silent during the war?

The fifth day of the war. I am meeting a friend at the Lviv railway station. We hug each other for a long time, silently.

The fourteenth day of war.

Friends who escaped from Bucha arrive. They have three children with them. One boy is silent the whole time. The Russians made him forget how to speak.

The twenty-first day of war.

The President announces that at 9:00 a.m., we would have a nationwide moment of silence for those who died as a result of Russia's armed aggression against Ukraine.

'I guess I should be quiet a little longer. Then I can tell you everything about war'

I’m surprised, since I remained silent for them for much longer than that. We will be silent for them not for minutes, but for years.

Since the start of the war, I have developed a cough – it chokes me as soon as I try to say something long and meaningful. Some say it's psychosomatic, while others say it’s because I sleep on the floor. Refugees sleep on the beds and sofas in my Lviv apartment (they say it's better to call them 'new neighbors', and that it's also better to keep quiet about the fact that they are refugees or IDPs).

Even when the sofa was later vacated (they went further west), I no longer wanted to sleep on it. I feel better on the floor – like those about whom I keep silent every day, even though they are still alive. It's a pity that they don't get any better from my coughing or my silence.

The fortieth day of the war. A friend tells me her friend was raped at a Russian checkpoint back in 2014.

My friend kept quiet about this story for eight years. Didn't we all already know what the occupation was?

The fifty-seventh day of war.

I remember that I promised to write an essay about the war. I am reading the testimony of a woman who escaped from Mariupol. She is a physical education teacher, and I am supposedly a famous writer. But I have nothing to add to her testimony.

I can only warn the reader that even she is silent about something — something unspeakable.

(picture Juan Vega de Soto)

(picture Juan Vega de Soto)

The fifty-ninth day of war.

I once again explain to my sister in Kherson why it isnecessary to evacuate from the occupied city, who is waiting for her in Kyiv and Lviv, what support would be available abroad, and so on. She writes back that she loves us all and asks me to stop convincing her as she has decided to stay. In response, I send her an emoji saying 'okay' in reply – that is, I remain silent. I don't know what to say to her anymore. I still ask her at times: 'How are you?' But these questions and our falsely optimistic answers are just as good as silence.

The sixtieth day of war. Easter. 'Christ is Risen!' I write in a message to the frontline. But he is silent. Silent.

I want to return to the time where teaching kids to go down to a bomb shelter is still considered crazy. But I can't remember what we were like then. And it is impossible to write about this war. I guess I should be quiet a little longer – one minute every day at 9 a.m. and for the rest of my life. Then I can tell you everything about war.

From the In Memoriam of PEN Club Ukraine:

Based upon interviews with witnesses, PEN Ukraine and Truth Hounds said earlier that the Russian shelling of a civilian object in a Ukrainian city was another war crime of the Russian army in Ukraine. The analysis of destruction and evidence from witnesses show that Russians use a high-precision Iskander missile. They clearly knew that they were shelling a place with many civilians inside. We know of 13 dead and about 60 wounded.

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Victoria Amelina has expanded her work far beyond literature. In 2022 she joined the human rights organization Truth Hounds. She has been documenting Russian war crimes on de-occupied territories in the Eastern, Southern and Northern parts of Ukraine, in particular in Kapytolivka near Izyum where she found a diary of Volodymyr Vakulenko, a Ukrainian writer killed by the Russians.

Amelina's first non-fiction book in English, War and Justice Diary: Looking at Women Looking at War, will be published shortly.

Amelina's Diary of Silence was published by the journal Apofenie in the translation of Yulia Liubka and Kate Tsurkan.