Russians are wary of raising the issue of collective responsibility for Stalinism, writes Dutch historian Gijs Kessler, because they don’t want to confront each other. Igor Torbakov disagrees. In response to Kessler’s essay, he stresses the persistence of authoritarian political culture in contemporary Russia as a decisive factor of ‘sociological communism’.

There are three observations in Gijs Kessler’s piece with which I agree:

1) the victims of the Great Terror are being mourned in contemporary Russia but Stalin appears to be genuinely popular;

2) Russian governing elites instrumentalize the memory of World War II for political ends; and

3) both the rulers and the ruled in Russia are reluctant to engage in what the Germans coined as Vergangenheitsbewältigung – the tackling of the ‘dark pages’ of the Soviet past.

It is Kessler’s overall conclusion that is problematic. He argues that the Russians’ reluctance to deal with their ‘difficult past’ – their choice in favor of remaining silent rather than of speaking out – stems from their fear of societal disruption. The Russians, Kessler contends, are wary of raising the issue of collective responsibility lest the descendants of Stalinist executioners and Stalinist victims not confront each other, triggering potential destabilization and turmoil.

I would beg to disagree and suggest that other sociological, historical, and mnemonic processes are at play here. It is the persistence of authoritarian political culture in contemporary Russia – common for both ‘elites’ and broad masses – that is a decisive factor in the continuation of what might be labelled ‘sociological communism’, by analogy with what Paul Preston has called ‘sociological Francoism’ in post-authoritarian Spain.

Past that refuses to pass

In contemporary Russia’s emerging metanarrative, the Soviet period is undoubtedly the most controversial element of the new Great Story. The ambivalent attitude towards the Soviet past can be explained by the fact that it never has become the past: as the saying goes, it’s the past that refuses to pass.

The stubborn persistence of all 'Soviet' in what has already been labelled as 'post-Soviet' needs to be explored in greater detail.

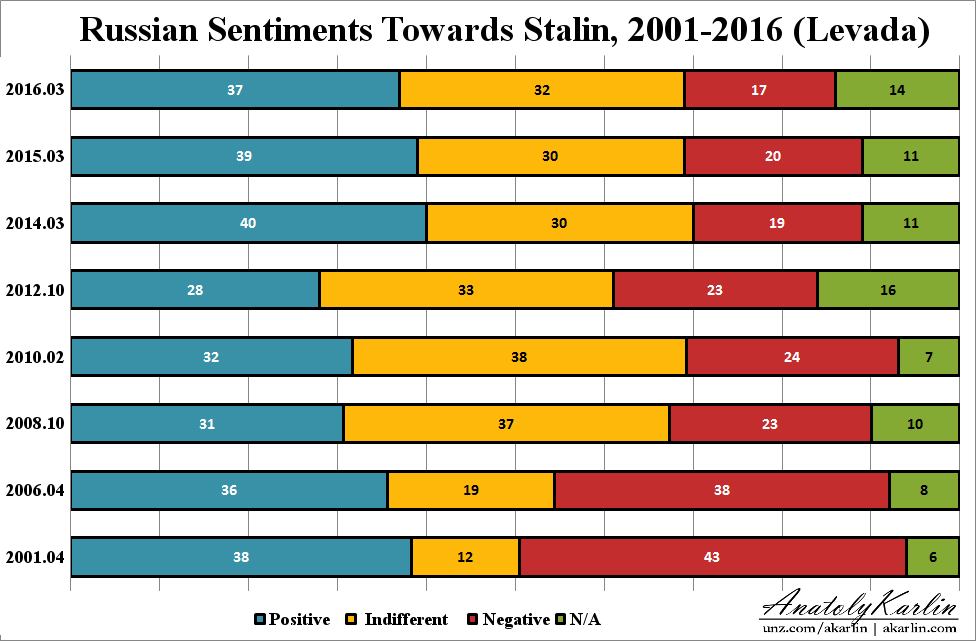

Opinion polls by Levada Center on changing attitudes vs Stalin

A pioneering research effort studying the characteristics shared by both the present-day citizens of the Russian Federation and the Soviet people was carried out by the Moscow-based Levada Center, a well-respected independent pollster. The study’s intent was to detect repetitive stable features that pierce through both periods across the 1991 divide. The research has singled out several basic features that are common to Soviet and post-Soviet Russians. These key characteristics, taken in their entirety, constitute a specific sociological model – a type – that appears to be represented by what came to be known as Russia’s ‘silent majority’. It is precisely this majority that provides the bedrock of the current political regime’s support.

Discontent doesn't undermine regime

The first characteristic is the perception of power as above all paternalistic, entitled to take comprehensive care of the population and of all individuals’ needs: employment, income levels, pension payments, personal security, etc. Remarkably, most Russians hold that the authorities are not up to the task; that’s why they constantly show dissatisfaction and discontent with the bosses’ performance. However, this discontent doesn’t undermine the ruling regime’s legitimacy: these complaints and demands towards the authorities don’t clash with the ‘hegemonic ideology’ of paternalism, as the ultimate goal of these claims is not regime change, but having the regime keep its promises.

The second feature is the widespread conception of power as a hierarchic structure headed by one person; while wielding enormous power, this person is basically not responsible for his actions. This ‘national leader’ is not a real policymaker – his program is irrelevant and his actions are not judged in terms of usefulness or effectiveness. At the same time, there’s a sense that the ‘leader’ is omnipresent – his personal involvement might right all the wrongs done by the second- or third-tier bureaucrats who are seen as those responsible for existing defects.

Finally, there is a persistent wariness of the outside world – a widely shared perception of Russia besieged by numerous enemies who want to do it harm. These attitudes should be seen against the following backdrop: more than half of present-day Russians don’t consider themselves as ‘Europeans,’ while even larger numbers (up to two thirds) hold that the deliberate encroachments of Western culture threatens to destroy the original ‘thousand-year’ Russian culture.

Reconciliation without truth

It’s clear that Russia’s symbolic politics cannot fail to be affected by the longevity of ‘Soviet man’. In the immediate aftermath of the Soviet collapse, the Yeltsin ‘democrats’ were intent to make a clean break with the Soviet past – with Yeltsin even musing about making the Russian Federation a legal successor of the pre-1917 Russian polity. Yet already by the mid-1990s, they toned down their anti-Soviet rhetoric and opted instead for a policy of tolerance toward the Soviet legacy, which then evolved into the policy of cautious reconciliation. Vladimir Putin’s rise to power ushered in a full-fledged reconciliation with all things Soviet and a new ‘patriotic mix,’ offering, in Frederick Corney’s words, ‘history without guilt or pain’ and ‘reconciliation without truth’. Treating the ‘Great Patriotic War’ as a ‘usable past’ fits into a broader strategy of ‘normalizing’ Soviet history which has been vigorously pursued under Putin. ‘Normalization’ of the Soviet past as ‘part of our glorious thousand year old history’ contributes to the revived ideology of statism as a perennial source of Russian identity.

Patriotic mix: history without guilt or pain

Integrating the Stalin period into a greater Russian story is not just an elite project — the polls demonstrate that it is supported by the masses. For the West in general and Russia’s Eastern European neighbors in particular, the process appears both puzzling and menacing; increasingly, there is talk about Moscow’s backlash and imperial comeback. There is, however, a compelling psychological reason for the rise of such public attitudes, and some more astute commentators contended that a backlash in one form or another was inevitable.

One has to understand, noted the late Tony Judt, that for the majority of Russians, the demise of the Soviet Union involved the loss of not just territory and status but also of a history that they could live with. ‘Everything has been unraveled before their eyes,’ said Judt, adding that any other nation would have been morally devastated by such an experience. ‘If this had happened to Americans, or Brits, it would have been culturally catastrophic; to lose the equivalent of, say Texas and California, to be told that all the founding fathers right down to FDR were a bunch of criminals, to discover that you are regarded as on a par with Hitler, in terms of the accepted description of 20th-century evils that we have since overcome.’

No wonder, then, that the ‘trope of loss,’ as Serguei Oushakine demonstrates so well in his The Patriotism of Despair, has become the most effective and widely used symbolic device which Russians employ to make sense of their Soviet experience in the post-Soviet context. There is, of course, a vexed question about the interrelation between the glory of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ and the horrors of Stalinist terror. Some liberal Russian scholars have skillfully demonstrated how the memory of the war is being (ab)used to construct a kind of ‘blocking myth’ in order to suppress the memories of the totalitarian regime’s terror, of the Gulag and other crimes of the period. If the atrocities perpetrated by the Soviet regime do occasionally pop up in the official narrative, they are presented as some insignificant episode in the otherwise heroic and glorious Soviet history.

But one must also bear in mind the existence of significant differences in the ways the trauma of the Soviet collapse affected public perceptions and memories of Russians and those of their neighbors in Eastern Europe. According to Oushakine, ‘In Russia itself, the disintegration of the USSR was linked much more closely with the painful immediacy of everyday survival than with archived horrors of the Great Terror… The need to equate the Soviet Union with the Stalinist regime, which was so crucial for many Western [and East European] commentators, was less obvious in the midst of [Russia’s] post-Soviet changes.’

Authoritarian political culture

Now, while discussing the (im)possibility of drawing parallels between German and Russian experiences, one has to be aware of historical perspective. The Germans began to be engaged in Vergangenheitsbewältigung not in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Nazi regime but two decades later, in the 1960s, with the famous Historikerstreit taking place in the late 1980s. Indeed, according to one survey of the Levada Center, around 49 percent of Russians believe that Stalin played a largely positive role in the country’s history, while only 33 percent hold that he was a negative historical figure. In a sense, however, this situation is similar to the one that West Germany experienced in the 1950s, when after the actual completion of de-Nazification campaign it turned out that Nazism had remained part of the national political consciousness, and one third of Germans were ready to justify it one way or the other.

Authoritarian leaders prefer to feed their subjects with ‘nursery history’

The most important obstacle preventing the Russians from facing up to their unsavory past is authoritarian political culture. As Karl Schlögel argues, ‘Authoritarian conditions are hostile to memory. A mature historical culture and a civil culture belong together.’

Indeed, scholars have noted the close correlation between regime type and the degree of regime’s reliance on historical myths. True, all regimes resort to and rely on myth-making. But in liberal democracies, political legitimacy is much less dependent on the unifying historical narrative that would foster compliance with government policies than it is in authoritarian regimes. Genuine democracies are thus much more tolerant of dissent, controversy, competing ideas and can afford the luxury of treating history that challenges habitual assumptions with relative equanimity.

This trait, in the words of the eminent British historian Michael Howard, is a mark of maturity. By contrast, authoritarian leaders prefer to feed their subjects with what Howard calls ‘nursery history.’ In his view, ‘[A] good definition of the difference between a Western liberal society and a totalitarian one — whether it is Communist, Fascist, or Catholic authoritarian — is that in the former the government treats its citizens as responsible adults and in the latter it cannot.’

Two posters of tow different leaders. Illustration Wikimedia.

Oversimplified perceptions

The second problem is the widespread perceptions of the masses about what history actually is. Sociological surveys demonstrate that in Russia as well as in most other post-Soviet states, people are largely unaware of one fundamental thing — that studying history is a complex and continuous process in the course of which what used to be perceived as ‘historical truth’ can (and should) be refuted as new evidence emerges or new interpretations are advanced.

According to recent data provided by VTsIOM, a Russian pollster, 60 percent of the respondents hold that history should not be revised, that past events should be studied in a way that would exclude ‘repeat research’ leading to new approaches and interpretations. Only 31 percent of those polled believe that the study of history is a continuous and open-ended process. Furthermore, 79 percent spoke in favor of using one single textbook when teaching history course in schools — lest the young minds get confused by alternative interpretations. Symptomatically, 60 percent said the passing of a ‘memory law’ criminalizing the ‘revision of WWII results’ would be a good thing.

This picture of public attitudes should correct an oversimplified perception of symbolic politics in Russia and other post-Soviet countries as a basically one-way street whereby the discourse that serves the interests of ruling elites is being imposed upon society. In more than one way, attitudes toward history and memory demonstrate a meeting of the minds between rulers and ruled in Eurasia.

Culture of shame

This brings me, finally, to the issue of moral responsibility. ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung, ‘overcoming’ the totalitarian past, theoretically speaking, is the ordeal that all nations have to face, that went through a totalitarian experience,’ argued Sergei Averintsev, Russia's leading humanist scholar not long before his death in 2004. ‘But actually not all of them realize the necessity of this process,’ he added.

Historically, Averintsev noted, the very idea of overcoming the past – understood as a comprehensive critique of a whole nation in contrast to the analysis of merely the leaders’ actions – is relatively new. The emergence of this idea is directly connected with the reflections of Karl Jaspers on the ‘question of German guilt’ in his celebrated 1946 essay ‘Die Schuldfrage.’ In this work, Jaspers famously discussed the four categories of guilt. In a legal sense, guilty is only he who committed concrete criminal acts, and this guilt should be proved in court. There is no collective guilt.

However, politically speaking all German citizens who lived under the Nazi regime are guilty, even those who considered themselves apolitical or were opponents of Nazism. Since they accepted the political system established by the National Socialists, they bear collective political responsibility vis-à-vis the community of peoples. In terms of moral guilt, there are huge differences between Germans who were adults during the Nazi era. The issue of whether one is morally guilty or not is decided individually, on the basis of individual conscience. And finally, Jaspers contends, there is a metaphysical guilt which is a ‘lack of absolute solidarity with people as people'. The experience of metaphysical guilt can and should change our self-consciousness. But no one can burden another with this experience – in this matter only God can decide.

Some scholars have long argued that human cultures differ in how they approach the issue of collective responsibility for sins and crimes of the past. According to the famous classification introduced by U.S. anthropologist Ruth Benedict, civilizations either have a culture of ‘guilt’ (‘conscience’) or a culture of ‘shame’. A culture of guilt (predominant in most Western Christian nations) puts special emphasis on an individual’s internal conscience, while a culture of shame focuses on the outward appearance of moral conduct. For nations that have a shame culture (for example Japan and some other eastern civilizations) under no circumstances one may lose one’s honor: all the family secrets should be kept securely in the cupboard.

Averintsev, too, argued that a culture of guilt is ‘evidently closely related to a high appreciation of penitence, which is associated with the Christian tradition.’ Ultimately, he contended, ‘the future of Europe’s freedom tradition will be conditioned by a culture of conscience.’

In the confrontation between these two types of culture in contemporary Russia, it is a culture of shame that is clearly favored by the Kremlin, as evidenced by Vladimir Putin’s oft-repeated mantra that “no one has the right to impose the feeling of guilt on us.” Ultimately, the path towards the Russian Vergangenheitsbewältigung will open up not when the large segments of the Russian population will suddenly decide that it’s time to stop keeping mum about Stalinist crimes as the latter had now receded safely into the distant past (the argument Kessler upholds in his essay) but when the majority of Russians will succeed in creating a political atmosphere in which a culture of conscience can triumph.