Be it at the end of Putin's presidency in 2024 or before, things will inevitably change in Russia. But in which direction? Will we witness a transition to more democracy or another chaotic meltdown? The West cannot stay aloof, as what happens in Russia is a matter of concern for the world as well. At the end of the Cold War the West offered a positive alternative, but now it is alienating ordinary Russians, writes Russian journalist Leonid Ragozin. The only message it must convey is full integration of Russia in the western world.

by Leonid Ragozin

As I reported on NATO’s Trident Juncture exercise in Norway in October 2018, I interviewed a number of senior European military officers and government officials on how they adjust their countries’ defence doctrine to the new reality of confrontation with Russia. Naturally, the conversation revolved around the threat of Russia’s potential attack, along the lines of its current aggression in Ukraine.

Something that struck me as alarming in these conversations was the virtual lack of ideas regarding what feels like a more plausible threat - that of an abrupt meltdown of the Russian state following the demise of Vladimir Putin’s regime. The economic, humanitarian and military impact of this catastrophic event will easily overshadow that of any new stunt the Kremlin might be plotting to undertake in the future.

May 2018, Putin's inauguration for his last term. Photo free of copyright

May 2018, Putin's inauguration for his last term. Photo free of copyright

Really, ask yourself what is more likely: Russia launching a suicidal attack on NATO members in the Baltics or Putin’s regime collapsing as a result of a nasty drop in oil prices, palace intrigue, or simply because it has been around for too long and exhausted its ability to consolidate a convincing majority of Russians?

Someone who seriously believes that the annexation of Crimea is a part of Kremlin’s grand plan to conquer the world or restore the USSR in its old borders, may claim that the former is more likely.

Back in the real world however, the annexation of Crimea was never a part of this non-existent plan, but a spasmodic reaction by a vulnerable political regime to the perceived threat of the West exporting the political technology of coloured revolution into Russia.

In the same way, the military incident in the strait of Kerch, deplorable and counterproductive as it may be, is not the start of a new big war between East and West, but the result of reckless improvisation of two adversaries with their own political agenda's.

Another Crimea?

It all started with the Bolotnaya protests of 2011 and 2012, which exposed the regime’s vulnerability [tens of thousands took to the streets in Moscow to protest election fraud - ed.]. Kremlin’s creative and media-savvy political operatives soon found an antidote. Ukraine’s Maidan revolution in 2013-2014 allowed them to outsource Russia’s domestic political conflict to another country. The Kremlin made Ukraine bleed and it also made sure that the scenes of it bleeding would haunt Russians in every news bulletin on TV and radio for years to come. It produced a vivid display of what would happen to dissenting Russians, should they take a revolutionary path.

That strategy worked brilliantly. These days Ukraine is not only mired in conflict, but it lags far behind Russia on every living standards parameter, while its progress in developing democracy or fighting corruption is questionable to say the least. Ukraine’s post-Maidan story for Russians serves as a cautionary tale, rather than as inspiration for Putin’s opponents.

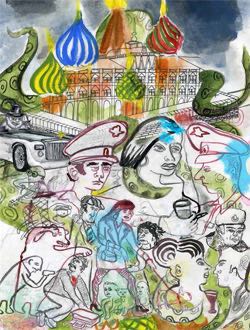

Illustration Chatham House

The annexation of Crimea, seen as an act of justice by the majority of Russians, sent Putin’s ratings soaring and temporarily demoralised the Bolotnaya crowd. But is there a second Crimea? The contrast with Donbas couldn’t be sharper. Even during the hot phase of the war in 2014-2015, polls showed that despite being carpet-bombed with toxic anti-Ukrainian propaganda, a majority of Russians opposed military intervention in Ukraine.

With the possible exception of Odessa, there is simply no other place in the world that has the same symbolic meaning for Russians and invokes the same sense of historical injustice as Crimea.

Besides, Ukraine is no longer the same low hanging fruit, which the Kremlin can grab at a relatively low cost. The West is certainly playing into Kremlin’s hands by either ignoring, or endorsing ultra-nationalism in Ukraine, but it will require major blunders by the Ukrainian leadership to turn another Ukrainian region into an easy trophy for Russia again.

Transition or Meltdown?

However, it all may change in a meltdown scenario, when the behaviour of the leadership or elements within it may turn suicidal. Then the probability of Russia - or a Russia-based rogue force - launching an attack on a neighbouring country or staging a war inside Russia rises exponentially.

As with all rigid, personified authoritarian regimes, a catastrophic meltdown is just as plausible as smooth democratic transition. Russia can take the path of post-Franco Spain in 1974 or post-Milosevic Serbia. Or it can become another Syria.

The pressure on the regime has been building up since 2011. Crimea gave the Kremlin a breather, but Putin’s popularity is now back to pre-Crimean levels, while the protest movement - as Aleksey Navalny’s presidential campaign has shown - simmers in pretty much every Russian region and now involves large numbers of teenagers and 20-year-olds.

A whopping 89 percent of Russians opposed Kremlin’s pension reform last summer in the first ever precedent when Putin, a classic majoritarian, had to go against the majority in order to replenish coffers depleted by his own populism and political adventurism.

Cracks in Power Vertical

Putin’s so-called 'power vertical' is also showing cracks. Recent regional elections saw people in several regions rejecting gubernatorial candidates from Putin’s United Russia in favour of the Communists. Meanwhile, several conflicts within the leadership showed that Putin may no longer be playing the role of the arbiter-in-chief in the shadowy oligarchic economy, while Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov has built a highly-militarised and autonomous dictatorial state within the Russian state and acts with increasing impunity both inside and outside his domain.

Illustration Julie Murphy

Some kind or tectonic shift, whether at the end of Putin’s current presidential term in 2024 or earlier, is simply inevitable. Economic indicators suggest that this transition could replicate that of Spain at the end of Franco or Chile at the end of Pinochet - that is, in the direction of democracy and greater prosperity.

No Beacon in Sight

Russians have a lot to lose. In terms of quality of life, the two decades under Putin were by far the best epoch for almost five generations of Russians since the start of WWI in 1914.

If you look at the GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity, you’ll find Russia at about the same level as Latvia and ahead of EU members Romania and Bulgaria. Russia’s GDP (PPP) is three times that of Ukraine - a major factor that explains why Russians are less prone to revolutions.

The downside though is that for the majority of Russians, economic success is synonymous with strong-headed anti-Western leadership, whereas the possibility of turning towards the West again evokes memories of the troubled 1990s or indeed of current troubles in Ukraine.

Based on their experience, an average Russian quite reasonably suspects that, should their country become more exposed to Western manipulations, they will lose both economically and in terms of security, especially if the West starts stirring up regional separatism the way it did in the 1990s.

Crucially, unlike the West of the early 1990s, which clearly served as a beacon for Russians after they toppled the Communist regime, the West of Trump and the Brexiteers is hardly a desirable role model for Russians today.

Dangerous Vacuum

The absence of a convincing role model, as well as of friends and partners they could really trust, leaves Russians in a political and cultural vacuum, which under certain circumstances may trigger suicidal behaviour. Add to that an extremely low level of mutual trust in Russia’s highly atomised society, as well as the lingering collective psychosis that stems from a century of genocide and utmost misery under the Communists, and the prospect of a trouble-free transition suddenly dims out.

The country may very well find a new Putin or become a democracy, but in the absence of a clear leader it may get bogged down in a dangerous confrontation between oligarchic groups vying for power. This is when private proto-armies, such as those of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov or 'Putin’s chef' Yevgeny Prigozhin, as well as large paramilitary formations masked as security departments of gas and giants, may come into the picture.

What’s at stake in a catastrophic scenario includes the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, ten nuclear power stations, dozens of hydropower dams blocking Eurasia’s greatest rivers, enormous stockpiles of ammunition and fleets of armoured vehicles, as well as multiple labs capable of producing bacteriological or chemical weapons, such as Novichok.

Vast majority of Russians live in high-rise apartments blocs existentially dependent on central heating and power supplies in winter. Any troubles with that, they’ll be pouring across the EU borders. Russia’s meltdown on a catastrophic scale poses an existential threat for Europe, which is why it is in the West’s best interests to start working on preventing it now.

Current State of the West

A fundamental problem in the meantime is the current state of the West. Visionless and rudderless as it is now, the West can very well do more harm than good if it intervenes to rescue a collapsing Russia. On the other hand, it is the only home Russians can return to from the political and cultural nowhere-land they find themselves in now. So there is not much of a choice.

The best thing the West can do in order to prevent catastrophic scenario's is to tell Russians - to the people, not leaders - that they are welcome. It means that, like every other East European nation, they are entitled to participation in Euro-Atlantic integration, provided they satisfy all the formal criteria for the membership in the EU and NATO.

Now of course that idea is an impossible sell in today’s West, which itself appears to be dragged into a suicidal mission by anti-EU nativists. So here is an axiom worth repeating by heart: there is no way Russia can be fixed before the West fixes itself.

The truth is that, three decades after the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, Russia is an integral part of the West, even though both sides will never admit it. Russia’s own domestic conflict between Putin’s brand of populism and Russian liberals precedes the current conflict between progressives and nativists in the Western world. To many opponents of Putin, Trump’s America or Orban’s Hungary in many respects feel like Russia in 2001.

A more vulnerable democracy, Russia was the first one to fell victim to the rising wave of populism. Back 20 years ago, it was a laboratory, where illiberal venom and fake news were tested on real people. But paradoxically Russia has never been more Westernised than it is now. It is a part of the Western cultural bubble and a grotesque mirror of the West itself, it’s own picture of Dorian Grey. What happens in and with Russia is very much an internal problem for the West.

By alienating Russia - not the government, but the people - the West is prompting them to take suicidal decisions. But that path is suicidal for the West itself too. Hopefully we will never witness a catastrophic meltdown of the Russian state. But equally, there is a certain chance that something will trigger exactly this five minutes after you finish reading this sentence.

Bold Positive Message of the West

This is why a bold, positive message that the West could send to Russians should be on the agenda today - not some time in a distant future. The only message that will work is the one that offers full integration. If the West is not ready to send it - and of course it isn’t - than it is in deep trouble and it’s own future is at stake. That's all the more a good reason to talk about it now.

Leonid Ragozin is a Russian journalist, based in Riga (Latvia). Ragozin contributes to The Moscow Times, The Guardian, Politico, Bloomberg, Buzzfeed, Businessweek, The New Republic and other newsmedia.