Last week a page with information on a draft decree on a Russian Government website led to questions as to whether the Russian Federation intended to put the maritime boundaries with its Baltic neighbors into question. On Wednesday, the page had been pulled down from the web. It led to speculations and political turmoil as to what this was all about. Law of the sea expert Alex Oude Elferink carefully read the draft and sees no reason to believe that Russia intends to change the internationally agreed sea borders.

Coast guard vessel in the Gulf of Finland. Photo: Finish Gulf Coast Guard

A screenshot of the page about the draft decree is available on X, allowing a detailed assessment.

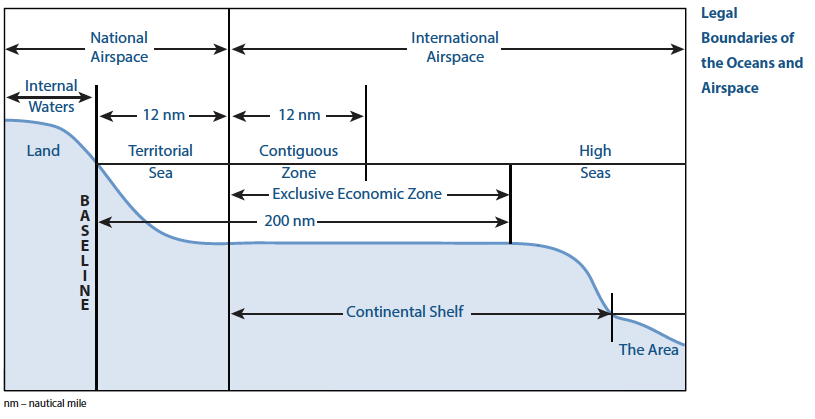

As is explained, the draft decree is intended to change existing Russian legislation that established the geographical coordinates of the points on the Russian coast for drawing so-called straight baselines. This may require some explanation for those not versed in the law of the sea. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), in which the Russian Federation, as most other States, participates, provides that the low-water line along the coast of the mainland and islands is the normal baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.

However, the UNCLOS allows coastal States to draw straight baselines if their coast meets specified conditions. Most States have drawn straight baselines along all or part of their coasts. In the Baltic Sea this includes Denmark, Estonia, Finland, and Sweden. Straight baselines replace the low-water line baseline and may result in extending the outer limits of, in particular, the territorial sea seawards.

The various maritime zones indicating the jurisdiction of a state. With each line farther from the coast the sovereignty of a state diminishes.

The various maritime zones indicating the jurisdiction of a state. With each line farther from the coast the sovereignty of a state diminishes.

The UNCLOS establishes that the territorial sea may have a maximum breadth of 12 nautical miles (approximately 22 kilometers). The outer limit of the territorial sea of the coastal States in the Baltic Sea, which generally is 12 nautical miles from the baselines, is identified by the red lines in the figure accompanying this article. The outer limit of the territorial sea is not permanently fixed, and will change if the relevant baselines from which it is measured change.

Beyond the territorial sea coastal States have an exclusive economic zone and a continental shelf, which have a breadth of at least 200 nautical miles measured from the baselines. Due to the dimensions of the Baltic Sea it is comprised in its entirety by the territorial seas, exclusive economic zones and continental shelf of its coastal States. As these maritime zones overlapped, the coastal States of the Baltic Sea have negotiated a large number of bilateral treaties to determine their maritime boundaries. These boundaries are identified by the dotted black lines in the figure of the Baltic Sea below. With the outer limit of the territorial sea, they delimit that area, and beyond that limit they delimit the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf. The boundaries of the Russian Federation with its neighbors have been highlighted in yellow.

Contrary to the outer limit of the territorial sea, agreed boundaries are not subject to change when the baselines of one or both of the States concerned change. It is a fundamental principle of international law that boundaries, once agreed, are final and binding. As has been observed repeatedly by the International Court of Justice ‘Once agreed, the boundary stands, for any other approach would vitiate the fundamental principle of the stability of boundaries’. This proposition applies equally to land and maritime boundaries.

All of the bilateral maritime boundaries of the Russian Federation – with Finland and Estonia in Gulf of Finland and with Lithuania, Poland and Sweden in the southeastern part of the Baltic Sea – in the treaties concerned have been defined in precise and unequivocal terms, specifying the geographical coordinates of the points, between which the boundaries concerned run as straight lines. These boundaries are final and binding and not subject to change in case the baselines of the Russian Federation or the State on the other side of the boundary were to change.

Map LRT. Yellow lines (added by the author): maritime boundaries of the Russian Federation with neighboring States – Not subject to changes if the baselines are changed. Red lines: outer limits of the of the territorial sea of the Russian Federation and neighboring States – If a state changes its baselines, the outer limits of its territorial sea may be subject to change.

Revision of baselines

Having clarified these preliminary matters, what does the document that caused all the commotion have to say? As the information page on the draft decree indicates, the Soviet Union had established straight baselines in among others the Baltic Sea in 1985 and this legislation never had been repealed. The system of straight baselines also included a straight baseline between what is now the territory of the Russian Federation and the territory of Estonia. The information page impliedly indicates that this straight baseline no longer is in existence.

Indeed, the Convention does not allow the drawing of straight baselines between points on the coast of two different States and Estonia has established its own system of straight baselines. As the information page indicates the absence of this straight-baseline segment prevents the determination of the inner limit of the territorial sea of the Russian Federation in that area. That is significant because the legal regime of the area landward of that limit – so-called internal waters – is different from that of the territorial sea. It seems reasonable to assume that proposed decree is intended to close this gap.

It is also indicated that the 1985 decree established the geographical coordinates on the basis of small-scale nautical charts, which, it is stated, are not completely in accordance with the current geographical situation. That does not seem unplausible, and the language that is used suggests that this is not concerned with major changes. It may be noted that the revision of straight baselines to keep them in line with geographical realities is a normal practice. It is further indicated that the revision also is concerned with the area of the cities of Baltiysk and Zelenogradsk in the Kaliningrad enclave.

State bounderies

So, does the information page have anything to say about the Russian Federation’s maritime boundaries with its Baltic neighbors? It does refer to the fact that the revision would ‘change the course of the State boundary of the Russian Federation at sea in connection with the change in location of the outer limit of the territorial sea’ (translation from Russian by the author). As this quotation indicates, reference is only to the boundary of the territorial sea, and not the limits of the Russian Federation’s continental shelf and exclusive economic zone.

The language that is used seemingly might be open to different interpretations as it might be read as being also applicable to areas where the limit of the territorial sea of the Russian Federation is determined by a bilateral treaty with neighboring States. This is the case for the entire territorial sea of the Russian Federation in the Gulf of Finland – bilateral boundaries with Estonia and Finland – and for the lateral boundaries of the Russian Federation’s Kaliningrad enclave – bilateral boundaries with respectively Poland and Lithuania. However, that interpretation would not be in accordance with the Act on the State Boundary of the Russian Federation of 1993, which provides that the State boundary at sea is formed by the outer limits of the territorial sea unless otherwise stipulated in international treaties concluded by the Russian Federation.

The draft decree does not read as a production of the Ministry of Truth but rather as a technical law of the sea treatise

In conclusion, there is nothing in the information page of the draft decree as available on X suggesting that the proposed decree would affect the maritime boundaries established by treaties between the Russian Federation and neighboring States in the Baltic Sea. The benefit for the Russian Federation of updating its straight baselines is that it brings them in line with the current of the relevant coastal geography and that it would close the gap in the straight baselines in the Gulf of Finland, clarifying the limit between the Russian Federation’s territorial sea and internal waters, in which different legislation is applicable. Amending these straight baselines does not affect the maritime zones and pose a threat to its Baltic neighboring States.

In addition, States may protest the straight baselines of another State if they consider that they have not been established in accordance with the relevant rules of international law. In that case there would exist a dispute over the legality of these straight baselines and until that dispute is resolved they are not binding on the protesting State. How this will play out in the case at hand at the moment cannot be predicted as there is no information in the public domain as to where exactly the proposed straight baselines would be located.

Reconstruction of the news story

That leaves the question what caused all the media attention. Of course, the Russian Federation’s foreign policy statements, among other those justifying its aggression against Ukraine, indicate a propensity to give an Orwellian twist to language. Still, the information document on the draft decree does not read like a production of the Ministry of Truth but rather a technical law of the sea treatise.

Political turmoil

On Tuesday May 21, the Russian Defense Ministry published a draft decree that would change its maritime baselines in the Baltic sea. Suspecting that this could mean that Russia would unilaterally change its sea borders with Lithuania and Finland, Lithuania immediately reacted with a strong worded statement, while the Finnish reaction was more restrained.

Lithuania’s foreign ministry called the proposal ‘a deliberate, targeted, escalatory provocation to intimidate neighboring countries and their societies’ in a statement to Politico, saying it is ‘further proof that Russia’s aggressive and revisionist policy is a threat to the security of neighboring countries and Europe as a whole.’ Finnish president Alexander Stubb found it suspicious that Moscow ‘not contacted Finland about this matter’. Finland would closely monitor the situation, he stated on X, meanwhile proceeding as always ‘calmly and based on facts’.

The same day Russian state media reported that according to a ‘military-diplomatic source’ the authorities were never planning to alter the boundaries. The next day, the document had disappeared from the Russian government’s website. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters on Wednesday there was ‘nothing political’ in the proposal to redraw maritime borders.

‘You see how tensions and the level of confrontation are escalating, especially in the Baltic region. This requires appropriate steps from our relevant bodies to ensure our security,’ Peskov said. Distrustful, the Lithuanian minister of Foreign Affairs Gabriellius Landsbergis wrote on X: ‘Another Russian hybrid operation is underway, this time attempting to spread fear, uncertainty and doubt about their intentions in the Baltic Sea.’ He called it ‘an obvious escalation’ against NATO and the EU, that should be met with a firm response.

Accordingly, Dutch acting foreign minister, Hanke Bruins Slot, stated on Friday May 24: ‘Russia’s provocative behaviour regarding the EU borders with Estonia, Finland and Lithuania is completely unacceptable. (…) Their borders are also our borders: we stand in full solidarity with our allies.’

It would also be interesting to delve into the evolution of this news story. One would suspect that the original source may not always have been checked very carefully, if at all. In addition, the fact that the page was pulled down from the Government site does raise questions. As is suggested by Kristina Spohr in her article ‘The Memo-Affair: Plan, Bluff, or Accident? Russia’s “Project” on Altering Maritime Borders in the Baltic Sea’ the upload may have happened accidentally and the page may not have been intended to be in the public domain. Perhaps, but the vociferous reactions of government officials from various Baltic States to which she also refers indicate the sensitivity of anything having to do with boundaries in the current political European setting and the deep distrust of the Russian Federation’s foreign policy designs on Europe.