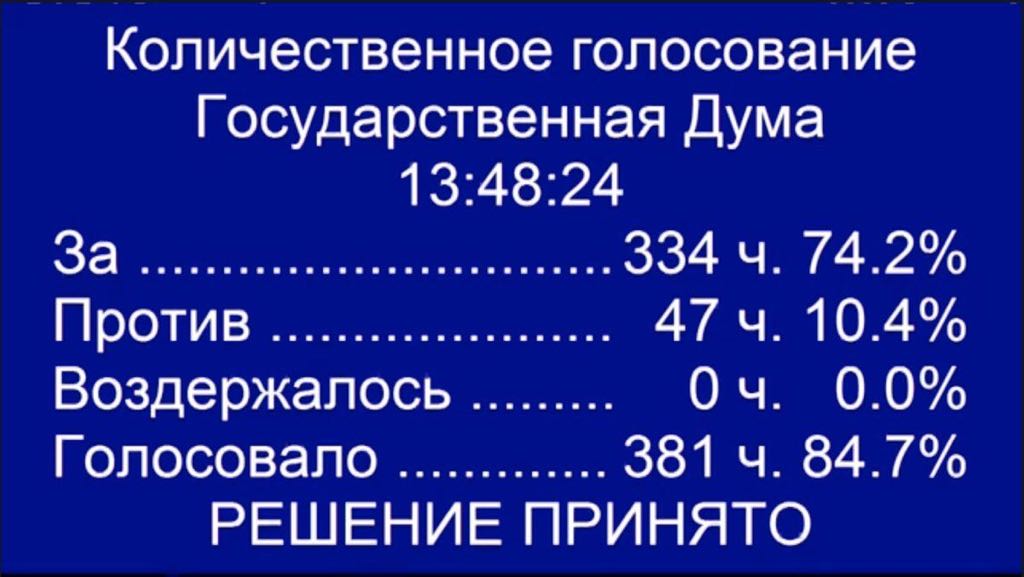

After six years of unabated attack on Internet freedoms in Russia, the Kremlin is making another bold step. The Duma in first lecture adopted a new law that can cut off the Russian internet from the world wide web. Almost 75 percent voted in favour of a bill that allows the government to seal off the country, by installing special equipment all over the country. Security specialist Andrei Soldatov reports.

A few years ago, I walked into a nineteen-story high rise, surrounded by a fence, in a residential district of southwest Moscow. At first glance the building could be mistaken for an average apartment block, but only twelve of the floors had windows.

This building was in fact the heart of the Russian Internet: the phone station M9, containing a crucial Internet exchange point known as MSK-IX. Nearly half of Russia’s Internet traffic passed through this structure every day. Yellow and gray fiber-optic cables snake through the rooms and hang in coils from the ceilings, connecting servers and boxes between the racks and between floors.

Each floor was protected by a thick metal door, accessible only to those with a special card. I had that card, thanks to the help of some engineers who agreed to help me in doing research for my book The Red Web: The Kremlin Wars on the Internet.

Big black boxes

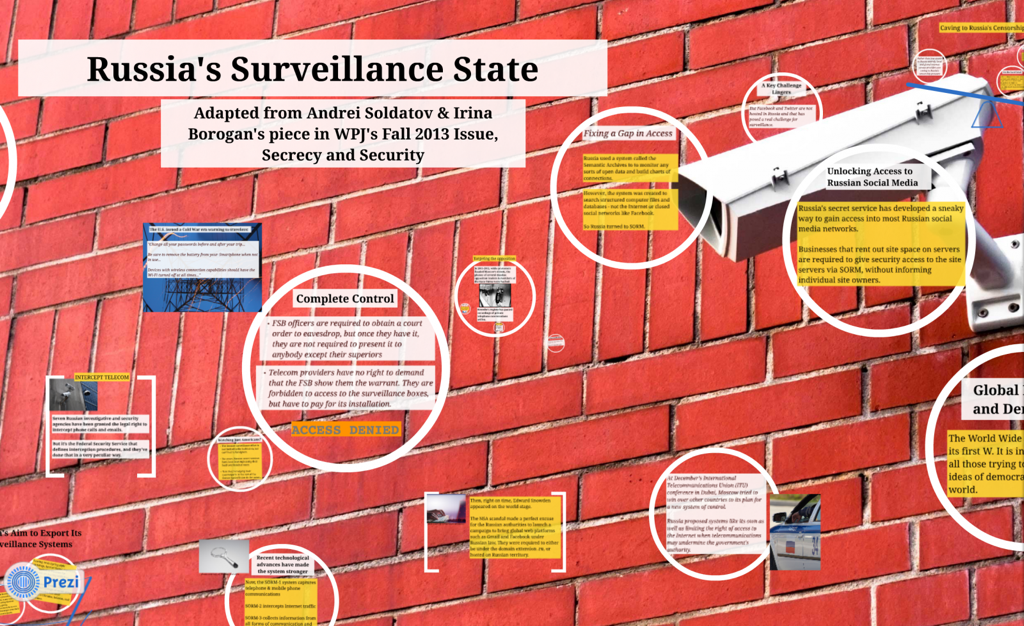

I knew that on the eighth floor there was a room occupied by the Federal Security Service (FSB), the main successor to the KGB. But the FSB’s presence was evident on all the floors. Between the communications racks throughout the building were a few black electronic boxes the size of an old VHS video player. These boxes were marked SORM, and they allowed the FSB officers in the room on the eighth floor to have access to all of Russia’s Internet traffic – the boxes mirror the traffic to the FSB.

I spotted one of the boxes between the communications racks, the small green lamp on it was blinking. I knew that similar SORM-marked boxes, connected to the local branches of the FSB, were installed all over the country on the premises of Russian Internet Service providers, being part of the wide-scale Russian surveillance effort. They were there since the late 1990s.

Back then I thought that these boxes looked both strikingly inefficient and old-fashionably Soviet. In the building, dating from 1979 and turned into a major Internet exchange point, Russian secret agents were sitting in a room surrounded by boxes of the size of VHS players, as an important part of the effort to control the Internet in Russia. How much information could they read or watch, let alone analyze? But that was not the point, the point was that every telecom operator present in the building was required to have this black box – its personal communication with the secret service.

SORM according to Soldatov and Borogan.

Only to censor?

I couldn’t imagine that just four and a half years later, in early 2019, Russian policymakers would decide to exchange these boxes with much bigger, much more powerful equipment.

The new boxes, soon to be installed on MSK-IX and elsewhere, have two major objectives. First, they will be able to block everything the Kremlin finds illegal – to censor the Internet, essentially. That objective is to be carried out on a permanent basis, 24/7. Second, the boxes make it possible to cut off the Russian Internet from the outside world.

This function, according to Kremlin design, is to be activated in case the Russian authorities feel that they are coming under the threat of political unrest or rebellion. All these boxes will be connected to a powerful ‘Center of Governance and Monitoring’, created specifically for that purpose and run by the Russian Internet censorship agency.

These boxes, along with the Center, are to be installed as implementation of the strategy to assert the country’s ‘digital sovereignty’ – essentially to give the Kremlin the power to have a decisive say on what goes on and what comes of the Internet within Russia's borders. The Kremlin just introduced digital sovereignty legislation to the Duma.

When approved (few believe it will not be), every Russian Internet service provider and Internet exchange point will have to install the new government boxes.

These new boxes, when put in place, mark a new era in the Russian government’s effort to control the internet.

Response to Bolotnaya-2012

This effort started in 2012, as the Kremlin’s response to Moscow’s mass protests, which erupted in response to the news of Putin coming back as president. The tricky thing was that before 2012, the Russian Internet was a completely uncensored space, and was developed by telecoms with no consultation or coordination with the government or secret services.

It didn’t stop the Kremlin. Constantly evolving, this effort always has one major objective – to strip the Russian Internet of any capability to get people out on the streets. More traditional means, like the opposition parties or trade unions, were brought to heel long before.

Thus, the Kremlin worked hard to give the censors and secret services the option to remove all Internet content deemed dangerous, and to identify troublemakers.

The SORM surveillance system was expanded and significantly updated. Internet filtering was introduced, along with a constantly growing blacklist of banned websites, videos and pages. Legislation was introduced to make it possible to send to jail those who posted dangerous things on social media.

This activity saw some successes – the persecution of bloggers affected the freedom of debate in Russian social media. Now people think twice before posting something about sensitive issues – the authorities, the church, the secret services, the Russian history.

However, the Russian authorities wanted to have another option at hand: since 2015 they have started developing the capability to switch off the entire country or a particular region from the outside world. In this regard, they have also achieved some successes.

Cutting of Magas

In early October of 2018, Magas, the capital of Ingushetia, a small republic in the North Caucasus, saw thousands of people gathering on the streets in what was to be a two-week protests. The local youth, some of them horseback in picturesque national costumes, holding national flags, went out to protest against a new settlement with the neighboring republic of Chechnya, which confirmed the loss of a chunk of Ingushetia’s land to Chechnya as part of land-swap with the neighbor.

People were angry, but not violent. Soon the youth was joined by elders, an important sign in the North Caucasus – a reflection of the wide support of protesters in the republic. This news was not welcomed by the central authorities in Moscow. After all, that region had suffered from a brutal civil war conflict just 15 years ago, and Moscow was following the developments with trepidation. But then it became worse. When the protesters kneeled down for a public prayer on the city square, they were joined by policemen in their uniform. To Moscow, it looked like a nightmare – ordinary people and policemen joined in manifesting their anger against something approved by the authorities.

Protest in Magas, Ingushetia. Picture RFE/Igor Smirnov

It was a powerful picture. Journalists and local activists streamed live what was going on the streets of Magas on different social media and websites. Until the Internet went dead. All three mobile operators in the region took down their 3G and 4G connection.

As it turned out later, mobile Internet connections were shut down on the request of the Russian secret services from October 4th to 16th, just at the time of the protests.

Leaks in digital curtain

Cutting off Ingushetia from the Internet worked relatively well, although it was done in a very straightforward Soviet administrative manner – the local operators were just told to shut down their Internet services. This special operation had some flaps - though protesters were deprived of their Internet connection on the streets, and video was no longer streamed live, information about the situation was leaking out from the republic. The region was not completely sealed off.

But it overall was a success. The government was determined to expand this model, though on a much more updated technological level, all over the country.

For that, the Kremlin needed more powerful boxes to be installed by Internet providers, which are connected to the Center of Monitoring and Governance – to be able to cut off a particular region from Moscow remotely and effectively.

The option of cutting the country off completely also seems to appeal to the authorities, and starting as early as 2015 the Russian government had drills trying to determine whether this was feasible (the first drill proved that information was still leaking out).

But the officials are determined to keep trying – the new legislation, among other things, also requires the Russian Internet providers to take part in such drills under government requests.

Cartoon (Photo: VyprVPN Twitter)

Intimidating global business

This ambitious idea, however, posed a technical problem for the Russian government. In the 1970s, the country could probably be sealed and isolated from the outside world by cutting the handful of subterranean cables laid between the Soviet Union and Finland.

But in 2019, the Russian Internet is truly global.

Not only is the country connected by many dozens of cross border fiber-optic cables, with over 30 operators owning them, but Russian Internet companies built and own also huge data centers in Europe. Amsterdam comes to mind first as the first country which opened the Russian network access to the European net. At the same time, global services have servers in Russia, in the heart of the Russian Internet infrastructure. For instance, Google came to MSK-IX more than ten years ago, in 2008, and had an entire floor rented there when I was at the Internet exchange point.

In the 1970s, the Soviet Union also didn’t have independent thriving telecommunications companies, unlike modern-day Russia.

One might think that these companies, which owe their success to the global Internet economy, would be in opposition to the China-like attempts to isolate the country.

Well, if the Kremlin knows one thing it knows how to intimidate local business.

In June 2014, Putin had a meeting with the top Russian Internet-entrepreneurs, including the heads of Yandex, the Russian version of Google which successfully competes with the American giant on the Russian Internet-search market, and Mail.Ru, the Russia’s leading e-mail service, part of the Internet holding which also owns the two biggest Russian social networks – VK (VKontakte) and Odnoklassniki.

The atmosphere at the meeting was tense, and only the head of Mail.Ru dared to ask the president about the repressive legislation on the Internet. Putin’s message to the leaders of the Russian Internet was blunt: ‘First of all, you can’t hide from us.’

That has to be proven absolutely true. Within two and a half years after the meeting, Yandex and Mail.Ru have both expressed their support for the digital sovereignty legislation which would require the Internet industry to install government boxes.

Technology vs. politics?

With lack of resistance from Russian Internet-giants, and the Russian audience largely ignorant about what goes on on the Internet, apart from a committed, but small community of activists, what else does the Internet have at its disposal to stand up to the Kremlin’s ideas of control?

The only hope is the Internet technology itself.

The Russian security services built a widespread system of surveillance, making sure every message could be intercepted. But thanks to the technology – HTTPS protocol and peer-to-peer encryption, they are helpless to decrypt them. The Internet of Things also presents a formidable challenge – the more telecommunications networks an ordinary user has at home, connecting his fridge, a TV set, or a garage door, the more difficult it is to cut off the connection. These days you can pick up a phone call on Skype on your smartphone and then continue your conversation on your TV set. How many lines, how many operators have get involved? It certainly doesn’t make things easier for the secret services.

Desperate move back to Soviet times

The Kremlin made a drastic move in 2016. In Russia’s Information Security Doctrine, updated every few years, the Kremlin stipulated that from now on, telecoms and IT companies should always consult with secret services ahead of introducing new services and technologies for their customers. In other words, security comes first, and technology second.

When the locals in Ingushetia complained that the authorities had cut off the Internet connection, they were told that everything was legal – the companies had complied with 'reasonable requests' of the secret services. It became clear that Ingushetia was a testing ground for a new strategy, and the first rehearsal had proved successful.

The success was to be continued, as the Duma has already passed in February 2019 in a first lecture a special bill to close the Russian internet from the outside world.

However, it certainly doesn’t look like a well-conceived strategy.

In a way, the Kremlin went against technological progress. Here, Putin imitates the Soviet Union’s approach, which curtailed technologies which the KGB suspected to be used for the uncensored dissemination and sharing of information.

It put the country at a disadvantage for decades, but it helped the Politburo to buy the country’s political regime some time.

Is that all the Kremlin wants now?

Duma vote in first lecture of new Internet bill: 75 percent in favour.

Duma vote in first lecture of new Internet bill: 75 percent in favour.