The Kremlin doesn’t understand the quintessence of Ukraine. Therefore Putin’s interventions since Euromaidan backfired: Ukraine is more orientated towards the West than ever before. But Putin invested so much in his confrontational politics, that he cannot simply retreat. Both Ukrainians and the West should stay firm to make him doubt before it’s too late, says the Ukrainian political analist Mykola Riabchuk. Which side will blink first in these unequal winter-games?

Anton Krasovsky, journalist at Russia Today, threatens Ukrainians in conversation with Alexander Baunov of Carnegie Moscow

As Russian political bullying and military blackmail, euphemistically called ‘Ukraine crisis’, intensifies, multiple recipes for possible ‘conflict solutions’ come from various corners. They greatly vary – from traditional calls to accommodate Russia by meeting its ‘security concerns’ (as if Ukraine threatens Russia and not vice versa) and to force Kyiv to comply with the achieved ‘compromises’, – to less popular but still reasonable calls to collectively confront the rogue state that terrorizes its neighbors and blatantly dismantles the international order.

Ukraine treated as an object

Ukraine has virtually no agency in these debates, being treated rather as an object than a subject of geopolitical developments. The experts typically assume that if the West and Russia fail to achieve some ‘compromise’ and impose it peacefully on Ukraine, Russia will the ‘Ukrainian question’ by force.

Ukraine’s history, however, implies that neither peaceful nor forcible imposition would proceed smoothly. Ukraine will rather resist like Poland in 1939 than give in like Czechoslovakia in 1938. The 20th century provides at least two examples of Ukraine’s resistance – in 1918-1921, against the Bolsheviks, and in 1945-1949, against the Soviets in the western part of the country.

Ukrainian’s nation-builders, regardless of their ideological preference, had little choice throughout the history but to lean toward the West as it was the only way to distance themselves from Russia. Secede or perish, that was the only way of survival vis-à-vis the Russian empire that had never recognized Ukraine’s distinct language, culture, and identity, and persistently strove to crush them – either by repressions or assimilation.

Secede or perish was the only way of survival vis-à-vis the Russian empire

The West as modus vivendi for survival

In a sense, Ukrainians had to be ‘Westernizers by default’: they had to accept Western values and discourses, even though they not always felt comfortable with them.

Ukraine’s Western orientation is not something imposed by a sinister West (that has been rather indifferent or even unaware of its existence throughout history), or by Ukrainian far right radicals (very marginal, in fact). Ukrainian pro-Western stance is its modus vivendi, its sine qua non for survival against a hostile neighbor who has never come to terms with Ukraine’s sovereign existence.

One might remember that it were not mythical far-right nationalists but it was the first Ukrainian post-communist president Leonid Kravchuk (and the communist-dominated parliament) who rejected Ukraine’s full membership in the Russia-led Commonwealth of Independent States in the early 90s, and also in the end fenced off many other integration initiatives promoted by Moscow.

It was Leonid Kuchma, another post-communist president (and a Russian speaker, if anyone cares, from the south-eastern city of Dnipropetrovsk) who, in 1998, signed a decree ‘On Reaffirming the Strategy of Ukraine's Integration into the European Union’ and, five years later, signed the law ‘On the Fundamentals of Ukraine's National Security’, adopted by the Ukrainian Parliament. Article 6 stated that Ukraine ‘strives for integration into the European political, economic and legal space with the goal of membership of the European Union, as well as into the Euro-Atlantic security space with the goal of membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’.

Remarkably, Kuchma’s prime minister at the time was the former Donetsk governor Viktor Yanukovych, who eventually as president mused on the Association Agreement with the EU, only to shelve the idea after forceful pressure from Moscow. This provoked the mass protests in 2013 and ultimately Yanukovych’s downfall in 2014.

Best of both worlds

Contrary to common Western wisdom, some consensus about Ukraine’s ‘European integration’ existed in Ukrainian society already long before the Euromaidan revolution of 2013-14, even though many people still hoped (rather naively) to combine Ukraine’s westward drift with good relations with Russia. Most did not, therefore, support Ukraine’s possible membership of NATO, fully aware of the sensitivity of that issue for Moscow. But neither did they expect that the purely economic agreement with the EU would evoke a similar wrath. To appease Moscow, Yanukovych officially adopted a non-allied status for Ukraine in 2012 and extended the rent of the Sevastopol naval base to Russia for another 25 years. It didn't help. In 2014, Russian forces occupied Crimea and staged a fake ‘rebellion’ in Donbas.

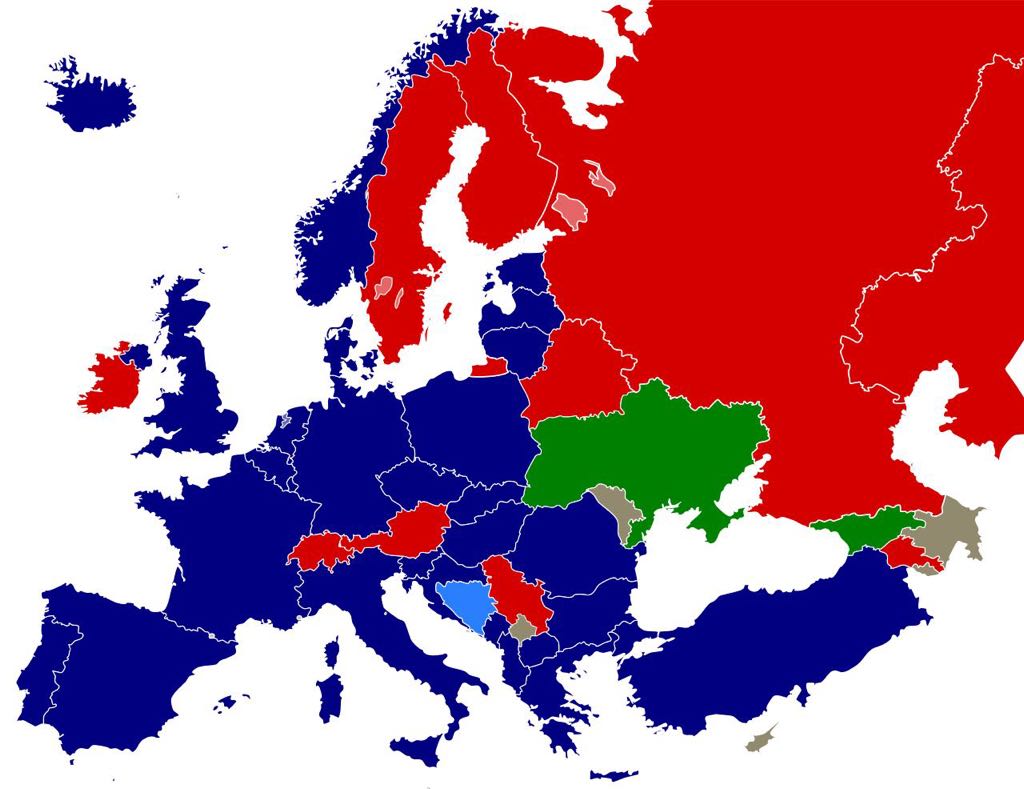

NATO-enlargement. Picture Wikimedia

Putin’s miscalculation

The Russian invasion didn't change Ukrainians’ predisposition toward the EU, as it had always been positive. But the invasion radically altered their attitude toward NATO, as all opinion polls since 2014 confirm. To a certain degree, this is caused by the exclusion from polling (and from taking part in national elections) of a substantial portion of the Sovietophile population of the Crimea and Donbas. But first and foremost this is the result from radicalization of the remaining part of the population. Moscow brutally taught Ukrainians that neither a non-allied status nor staying outside of NATO would give them security vis-à-vis a rogue neighbor.

Today, 73% of respondents in nation-wide polls support Ukraine joining NATO, while 21% is against membership. Figures, indeed, vary across regions, with a clear majority for membership in the West and more plurality in the East; the same variation is visible across the major ethno-linguistic groups, but in all cases, it is rather a matter of correlation than causality. Even more striking is the support for national independence – it varies from 92% in the West to 68% in the East, and from 90% among Ukrainian-speakers to 70% among Russian-speakers.

Finally, the latest survey indicates that 50% of Ukrainian citizens are determined to defend their country against a Russian invasion (37% with arms, including 26% in the allegedly ‘pro-Russian’ East).

Ethnicity increasingly irrelevant

In 1991 [when becoming independent) Ukraine was conceived as a civic nation, with inclusive citizenship and minority rights, and this type of identity is promoted today by both the state and civil society. This makes the notion of ethnicity increasingly irrelevant in political terms, downgrading it to purely private issues like religion or political affiliations. Moscow apparently cannot grasp that ethnic Russians and Russophones in Ukraine are first and foremost Ukrainian citizens, who benefit from broad civic rights and political freedoms unimaginable in today’s Russia. They elect their presidents and MPs in competitive elections, freely criticize and dismiss them, and have little appetite for a Moscow-style dictatorship.

Mass demonstrations at Kyiv's Maidan Square in 2014 provoked annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbas

Mass demonstrations at Kyiv's Maidan Square in 2014 provoked annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbas

Ukraine is a democracy, though imperfect. This means, inter alia, that whoever is president of the country and whatever policies he/she is forced to implement by the West, or by Russia, or both, he/she must first of all listen to his/her own citizens and follow them or at least persuade them that his/her suggested policies are reasonable and acceptable.

Compromises are always possible – if they do not put at risk the nation’s sovereignty and functionality (as, for instance, the Minsk agreements in the Russian interpretation apparently do). Ukrainians may postpone their claims for NATO membership a while, if they get clearer prospects for membership in the EU in exchange – a signal that they are not abandoned by the West and left at Russia’s mercy. It is unclear yet whether the EU is able to make such a bargain, and even less clear whether Russia would like to accept it.

Bizarre beliefs

The Kremlin major concern is certainly not a mythical ‘NATO threat’ but a free, democratic and prosperous Ukraine that undermines Putinism by its very existence – by offering Russian’s an alternative, European model of development.

Russian policy versus Ukraine is determined by two fundamental ideological-cum-psychological complexes: (a) dissatisfaction with the post-cold war global order (including Putin’s personal resentment) and a desire to revise it, specifically in Eastern Europe, and (b) a sincere, however bizarre belief that Ukrainians are merely a regional brand of Russians and therefore should be brought back to the Russian fold, regardless of their own beliefs and desires.

The first complex makes Russia into a dangerous revisionist power striving to bring Europe back to Yalta and notorious ‘spheres of influence’. The second complex makes the Russian elite's and Putin's in particular obsession with the ‘Ukrainian question’ nearly as paranoid as the German leadership back in the 1930s was obsessed with the ‘Jewish question’.

There is an important difference, of course: while the Nazis considered all Jews wicked and doomed to extermination, the Russian approach to Ukrainians is more flexible: they make a distinction between ‘good Ukrainians’, who accept the ‘sameness’ with Russians and therefore can be spared and even promoted, and ‘wrong Ukrainians’, who should be destroyed.

As one of Putin’s geopolitical gurus Alexander Dugin wrote in 2014 (when Ukrainians unexpectedly met Russian invaders in Donbas with arms rather than flowers): ‘I can’t believe these are Ukrainians. Ukrainians are wonderful Slavonic people. And this is a race of bastards that emerged from the sewer manholes... We should clean up Ukraine from these idiots. The genocide of these cretins is due and inevitable...’

In other words, the Ukrainians have chances to survive as long as they fit Dugin’s notion of ‘wonderful Slavonic’ folk or Putin’s notion of ‘the same people’. Otherwise, they should be prepared to meet their fate as ‘bastards from the sewer manholes’ – or, as the Russian state-run TV host, Anton Krasovsky recently threatened on public tv: ‘We will invade Ukraine. We will take your Constitution and burn it on Maidan, and we'll burn you [Ukrainians] too. Ukraine is our land!’

President Zelensky at NATO headquarters. Picture NATO

Are Europeans ready to sacrifice a few dollars?

The two imperatives – the Russian desire to subjugate Ukraine and the Ukrainian desire to preserve sovereignty and European orientation – makes any viable compromise between Moscow and Kyiv virtually impossible. Moscow is fully aware of this and therefore strives to negotiate an agreement with the US rather than with Ukraine. But the US (and the West in general) can barely meet Moscow's demands because (a) Ukrainians are determined to defend their sovereignty either with or without Western help, so the West cannot press them too much without an inevitable backlash. And (b) too much pressure conflicts with basic Western values and principles.

The West must, nolens volens, meet Kyiv's demands for help – both in the form of military assistance (short of sending in troops) and in the form of the harshest possible sanctions against Russia (and the Russian elite in particular) in case of aggression.

The mantra that sanctions don’t work is false. They do not work only as long as they are too weak, superficial, and incoherent. Russia is neither Iran nor North Korea. The Russian elites hold their money and property, their wives and children and mistresses in the West, and enjoy a dolce vita in Western resorts. They are very vulnerable, in fact, to real, not just declarative sanctions.

The only problem is that the sanctions are costly for everybody, so that each citizen of the US or EU may also suffer the loss of a few dozen dollars. Whether Ukrainian lives are worth this sacrifice, is a tough question that Westerners should ask themselves.

Opportunist Putin

Putin’s regime is highly opportunistic, even though it plays with the image of ideologically obsessed and unpredictable. Putin and his men are adventurous but risk-averse; they are aware that a serious failure may lead to the regime’s end. Before they attack anybody, they want to know that the victory will be easy and that the loses will be minimal. Both Ukrainians and the Westerners should make them to doubt.

Putin invested too much into this confrontation, so he cannot merely give it up and go out empty-handed. The most likely scenario therefore seems to be not a large-scale invasion but a disguised advance of Russian troops in Donbas, like they did in 2014-15, as so called ‘rebels’. If they manage to reach Transnistria or Crimea, it would be perfect, but if they merely ‘liberate’ the rest of Donbas, it would be also fine.

In this case western sanctions will be escaped, or minimized, because the Russian involvement again, like eight years ago, will be deniable. In the meantime, Putin may score a media victory by rescuing, once again, his ‘compatriots’ in Donbas from Ukrainian genocide and by officially recognizing the People’s Republic in Donetsk and Luhansk as rightfully seceding from the Ukrainian failed and crypto-fascist state, turned to an American protectorate. He would secure his political survival for another few years as a fearless challenger of the Western hegemony, savior of the Eastern Slavs, and indispensable defender of the besieged fortress called ‘Russia’.