A number of Central European states have announced a ban on agricultural imports from Ukraine. On April 15, Poland was the first country to announce a ban, quickly followed by Hungary and later Slovakia. The issue puts the European Union at odds with five of its Central and Eastern European member states. A team from think tank OSW takes stock on the grain issue.

A farmer's protest in Poland, April 13. Image Facebook.

A farmer's protest in Poland, April 13. Image Facebook.

The war doubled the import of Ukrainian food to the EU. In particular, this applies to cereals, the sales of which doubled from 7.8 million tonnes in 2021 to nearly 16 million tonnes a year later. The export of agricultural products was already of key importance to Ukraine before the Russian invasion, and its role has increased since. Although agricultural exports fell by around 15%, this drop was much smaller than in other important sectors.

Poland, Hungary and Slovakia ban Ukrainian imports

As of April 17, three Central European countries have announced a ban of agricultural imports from Ukraine: Poland, Hungary and Slovakia. Bulgaria says to be 'considering' a ban as well. The countries seek to protect their domestic agricultural production, which struggles to compete with the much cheaper Ukrainian imports. The European Commission has called the measure 'unnacceptable', stressing that trade policy is an exclusive competence of the European Union.

Poland was the first country to announce the ban. The announcement came after several weeks of political unrest and a wave of farmers' protests. The three countries have stated that the transit of grain to other countries will remain possible and that the ban is merely meant to prevent sales within their domestic markets. Hungary's minister of Agriculture has said that his country joined the Polish ban 'in the absence of meaningful EU measures'.

The Ukrainian minister of Agriculture, Mykola Solskyi, expressed hope that the issue will be resolved: 'We understand the tough competition that resulted from the blockade of Ukrainian ports. But, it is obvious that the Ukrainian farmer is in the most difficult situation. And we ask the Polish side to take this into account'. Solskyi said that he is confident that the countries would come to an agreement, considering the 'firm and ongoing cooperation' between the two countries.

On April 18, according to Ukrainian and Polish officials, the two countries indeed came to an agreement about Ukrainian grain. Poland would continue to allow the transit of grain through its borders, on the condition that the transports be sealed, monitored and guarded to ensure that the products would not reach Poland's domestic market. Polish Agriculture minister Robert Telus stated that this monitoring would take place using traceable devices, so that 'not a single ton of [Ukrainian] grain will remain in Poland'.

Grain deal and solidarity corridors

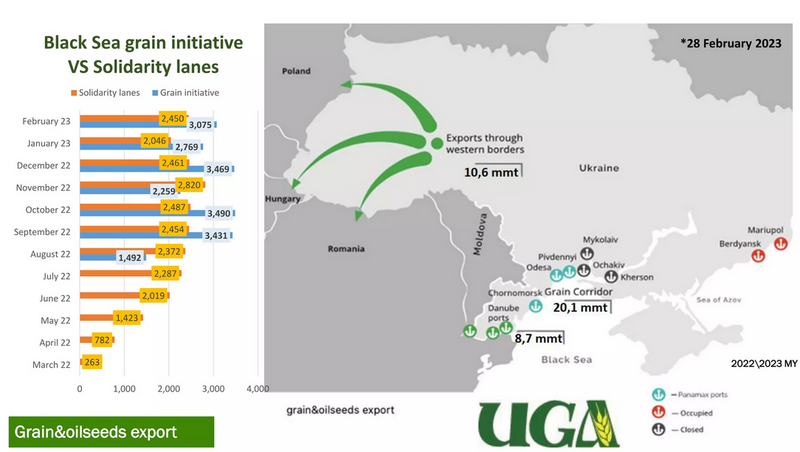

Before the war, two-thirds of Ukrainian exports were transported through ports on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. For agricultural products, this number was over 90%. The Russian invasion resulted in the occupation of some Ukrainian ports and the blockade of others. This made it necessary to find alternative export routes. To facilitate trade, in May 2022 the EU established the so-called solidarity corridors, in which Poland and Romania played the main role. A significant amount of grain is now exported through the port in Constanța, Romania, as well as by land through Poland.

At the same time, Ukrainian agricultural producers were looking for new markets for agricultural products. Their attention was focused on neighboring countries. Before the war, neighboring countries imported small amounts of cereals and oilseeds, but from March 2022, their import from Ukraine began to increase rapidly.

Green ports and corridors used for the export of grain and oilseeds.Map Ukrainian Grain Association

Green ports and corridors used for the export of grain and oilseeds.Map Ukrainian Grain Association

The increase in agricultural imports from Ukraine was not evenly distributed among EU countries. While neighboring countries, which previously practically did not import grain from Ukraine, began to buy huge quantities after the outbreak of the war (Romania, for example, recorded an over 800-fold increase in imports), in many countries that are traditional recipients of Ukrainian grain in the EU (such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Portugal) decreases were recorded.

In July 2022, Russia and Ukraine agreed on a grain deal, which enabled the export of food from Ukrainian ports on the Black Sea. The first ships began sailing on August 1. From then until the end of March 26.4 million tons of agricultural products (mainly cereals, oilseeds and vegetable oils) were exported in this way. Because of the grain corridor, ports regained their dominant role in agricultural exports, reaching 75% last December. However, this is still significantly lower than before the invasion, pointing to an increase in export over land, mainly to and via EU neighbours.

Market disturbances in Central Europe

Over the last year, new logistic chains have been created, even as Black Sea ports have been partially unblocked. In June 2022, the EU lifted of customs duties and tariff quotas on Ukrainian exports. This made importing Ukrainian products into neighboring countries profitable, especially for regions close to the EU border. This development is seen mostly in grains and oilseeds.

In Central European countries, which have been net exporters of cereals and oilseeds for years, imports from Ukraine for the first time began to play an important role on their own markets. In absolute numbers, Poland became the largest recipient of grains and oilseeds among these countries. In relative terms, the largest share of cereals from Ukraine was seen in Slovakia and Hungary, while for oilseeds, it was Bulgaria. This development caused a drastic drop in prices, spelling trouble for local farmers trying to sell last year's harvest.

Romania: lower prices, higher costs

Starting this spring, financial losses in connection with the influx of Ukrainian grain became an important topic in Romania. In mid-March, the European Commission announced a compensation fund of 10 million euros to Bucharest as compensation for farmers who lost a significant part of their profits due to the growing export of Ukrainian grain to Romania and its transit through Romanian ports. Bulgaria was allocated 17 million, Poland less than 30 million. Romanian farmers estimated their losses at around 200 million euros.

Romanian farmers and parties critisize the 'ultra-bureaucratic' European Commission

Agricultural associations argue that the issue is not just the low price of imported grain (reducing the competitiveness of their own production and forcing them to reduce prices), but also the fact that the transit corridor through Romania led to a fivefold increase in logistics costs. The availability of trucks, freight cars and barges has been significantly reduced. As a result, some Romanian farmers were unable to sell their grain. Wheat prices have fallen by as much as 35%, with farmers also claiming that grain supplied to Romania from Ukraine does not meet quality standards.

Romanian farmers protest against cheap import Ukrainian products. Screeshot from Youtube

Romanian farmers protest against cheap import Ukrainian products. Screeshot from Youtube

The EC's decision to grant Romania the aforementioned 10 million euros for compensation caused indignation among domestic agricultural producers, who considered this amount 'offensive' and announced protests - the first one took place on April 7. Some agricultural associations officially refused to accept the financial aid. The situation faced by Romanian farmers has also led to political tensions. Coalition parties have criticized one another and the 'ultra-bureaucratic' European Commision, which, according to Romanian president Klaus Iohnnis, is not taking into account the sacrifices that Romanian farmers make. The opposition, meanwhile, blames the insignificant compensation fund primarily on the Minister of Agriculture, who, according to the opposition, started looking for help too late.

Bulgaria: farmers' protest amid election campaign

In Bulgaria, Ukrainian agricultural products are also an important topic, although so far it has been obscured by the parliamentary elections, which took place on April 2. The issue was not featured in the main parties' campaigns. The interim government and politicians from the largest parties (except for the pro-Russian Renaissance party) avoid making statements that could be considered hostile towards Ukraine. Instead, they focus on seeking more support from the EU and solving this problem at a supranational level.

At the turn of March and April – the last week before the elections – several hundred Bulgarian farmers protested. They demanded that Bulgaria not extend the EU regulation on duty-free imports of agricultural goods from Ukraine and demanded a higher compensation than the 17 million euros announced by the EU. They blocked an important highway and several border crossings with Romania leading to the port of Constanta. On April 7, another protest - this time coordinated with agricultural organizations from Romania - was held to block access to this port.

The protests were supported by the interim government of Galab Donev, who is still in power. The Minister of Agriculture, Yavor Gechev, symbolically took part in one of the blockades, during which he drove a tractor blocking the E79 road. He called on the EU to provide more extensive compensation for farmers, claiming that the announced amount of support was too low. The head of the Ministry of Agriculture emphasizes that 'countries located closer to Ukraine pay a higher price for the war.' At the same time, he emphasizes that Sofia supports the creation of European corridors for the import of Ukrainian grain, but they cannot be created 'at the expense of domestic farmers.'

Sixty percent of domestic crops for which there is no market are in storage

The government and agricultural organizations point out that the biggest challenges for Bulgaria in connection with the import of Ukrainian grain and oilseeds are the low purchase prices of grain and the storage of domestic crops for which there is no market. The import of sunflower seeds, for example, was 20 times higher in 2022 than it was in 2021. Farmers and the ministry emphasize that the market is not only Bulgarian, but that other countries around the Black Sea are also unable to absorb such large volumes of cereals and oilseeds.

As a result, more than 60% of the country's annual sunflower harvest is in storage and there are no buyers for it. Farmers' organizations estimate that this is now also the case for around 60% of wheat crops. The lack of sales for domestic cereal products causes fear among farmers about this year's harvest, which in Bulgaria begins in June. Grain production generates around 10% of the country's GDP, making the country - along with Romania and Serbia - one of the regional leaders in grain trade.

Slovakia: threats to domestic farmers

In Slovakia, the issue of the influx of cheaper Ukrainian grain, has not been a main topic of public debate. The issue is also not used by the opposition, even though the opposition regularly employs pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric and heavily exploits the issue of combating 'high prices'. However, agricultural imports from Ukraine are a significant problem for the domestic agricultural industry, which puts pressure on the government to take appropriate action.

Prime minister Eduard Heger noted on March 31 that the so-called Solidarity corridors were primarily intended to transport Ukrainian grain to third countries. Because of low prices, a significant part of the grain remained in the Central European EU member states, including Slovakia, which caused problems for local farmers with the sale of domestic crops. In this situation, the government tried to divert attention from Ukraine as the source of the problem, pointing out that it would not have arisen had it not been for the Russian invasion of Slovakia's eastern neighbor. Although the topic was not widely discussed in Slovakia, it was raised the head of coalition party We Are Family, Boris Kollár, who warned that inaction could 'decimate Slovak farmers'. Kollár called for financial compensation from the EU.

Truckers wait in long lines at the Polish border after Poland decided to ban grain and oilseeds from Ukraine. Screenshot from YouTube

Truckers wait in long lines at the Polish border after Poland decided to ban grain and oilseeds from Ukraine. Screenshot from YouTube

At the beginning of March, the Ministry of Agriculture started inspections in mills and bakeries. Their purpose is to check whether flour from Ukrainian grain is used in a way that is not in accordance with regulations. For example, it concerns the control of quality marks or compliance with the rule that 75% of flour must be made from domestic raw materials. The food inspection agency points out that although flour and grain from Ukraine are safe, they are not produced according to the same rules as in the EU.

Slovakia is self-sufficient in grain, exports amount to about 40% of the Slovakian production. The main export markets are the neighboring Czech Republic, Austria and Germany, while Slovakia's traditional competitors in this field are Romania and Hungary.

Hungary: emphasis on regional cooperation headed by Poland

In Hungary, the issue of Ukrainian grain is raised primarily by trade organizations, while the authorities focus on accusing the European Commission of an inadequate response to this crisis. Despite the cool Hungarian-Ukrainian relations in the context of disputes over the Hungarian minority in Transcarpathia and Budapest's position on the war, the grain issue has not been used to criticize Kyiv so far. The government also emphasizes the successes of regional cooperation in Central Europe and Poland's leadership on this issue.

The Hungarian grain harvest in 2022 was exceptionally low (a decrease of 36%) due to a severe drought. Over a million tons of cereals and oilseeds flowed into the country from Ukraine last year, compared to 50-60 thousand tonnes in previous years. The unprecedented quantities of Ukrainian grain reaching Hungary have created a surplus in local warehouses, destabilizing the grain market and leading to a significant drop in prices.

In February, the Ministry of Agriculture accused Brussels of 'only passively watching' as Ukrainian grain destined for North Africa and the Middle East got stuck in Europe, which led to serious market disturbances. István Nagy was among the five regional agriculture ministers demanding that the EC take anti-dumping measures to stabilize the situation on domestic agricultural markets. Both goverment and the industry also point to the quality of Ukrainian products, which are said not to comply with EU standards.

Prospects of Ukrainian agricultural production

Last year's harvest in Ukraine was nearly 40% lower than in 2021, which was mainly due to the Russian invasion. The decreases were observed mostly in cereals, and to a lesser extent in oilseeds.

Ukrainian harvests will shrink further in 2023 and reduce the export

Forecasts for this year predict a further reduction in agricultural exports, resulting from lower harvests. In the case of cereals, estimates indicate a decrease of around 15%. In total, the sown area in 2023 will probably shrink by around a quarter compared to 2021. This is the aftermath of the occupation of parts of the country and the fact that many fields were mined, which makes it impossible to carry out agricultural work. Most likely, this will reduce the agricultural exports to Ukraine's neighboring countries. The restoration of customs duties and quotas, which Central European states have argued for, will have similar effects.

A potential problem is the possibility of Russia breaking the grain deal. If it were to happen - although this seems unlikely, as Moscow has already extended the agreement twice - there would be a renewed increase in pressure on the countries neighboring Ukraine.

This article is an abbreviated and updated version of an article first published by OSW.