With a concert on Maydan Square Ukrainians celebrated that since June 11 they can travel to European countries without a visa. 'Farewell, unwashed Russia, land of slaves, land of lords,' president Poroshenko quoted Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov. Will a wave of Ukrainians engulf Western Europe in search for jobs? Not likely, says Kostiantyn Fedorenko. Labor migrants from Ukraine tend to seek jobs in Poland and the Czech Republic.

Ukrainians in Kiyv celebrate first day of visafree travel to Europe

Ukrainians in Kiyv celebrate first day of visafree travel to Europe

It took Ukraine eight years to fulfill the list of the European Union’s demands for visa-free travel. This was followed by a lengthy process of adopting the decision in Brussels and the European capitals, but at long last, Ukrainians can sigh with relief. Visa liberalization became a fact. Ukrainian tourists will find it much easier to travel to Europe. Could it also lead to a mass migration of Ukrainians looking for income and work, as many European voters fear?

Let us be clear: legally, the visa liberalization does not allow working in the EU. When a Ukrainian crosses the border and receives a stamp in his or her passport, he/she may stay 90 days in the Schengen area during any given 180-day period, and that’s it. A visa-free regime is nothing else but lifting the bureaucratic hurdles for short visits. However, in reality, people could enter the Schengen zone under false pretenses, and find work there illegally.

This was likely one of the key reasons why it took so long before the EU granted the visa liberalization to Ukraine. Western Balkan countries, Moldova and Georgia were already exempted from visa requirements when Ukraine was still waiting; but then their population, taken together, is less then 24 million. With a population of 42 million and the second worst economy on the continent after Moldova by GDP per capita (according to 2016 IMF data), Ukraine is playing in different league.

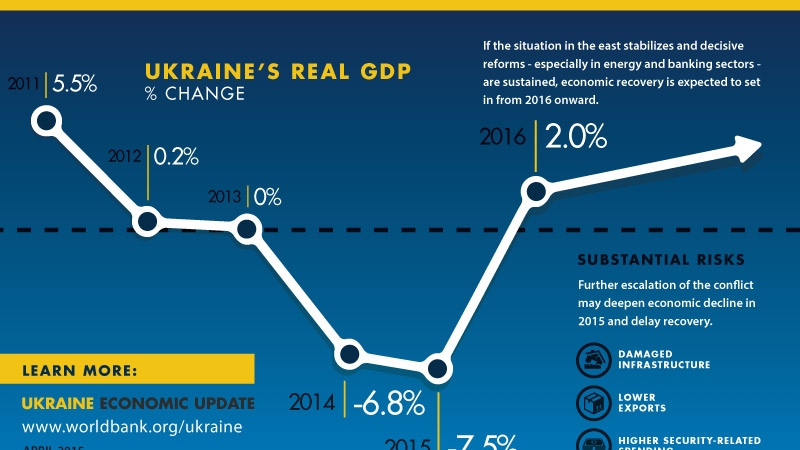

Its economic conditions are not likely to improve fast, too. Ukraine’s currency depreciated more than threefold against the euro since 2013 due to both internal factors and the armed conflict in the East that led to a drop in investments and a loss of industrial capacities in the rebellious regions. Gradual recovery is expected by the World Bank; but in the coming years, the growth will stay slow, at around 2-3% of the GDP. Therefore, while Ukraine has stabilized after its 2015 freefall, its economy remains fragile and the socioeconomic condition of its citizens insecure.

Crossing borders never complicated

To enter the EU since 11 June has become easier. But it is disputable whether it will significantly increase the number of Ukrainian illegal workers in Europe. For a Ukrainian determined to find employment in the EU, it was never that complicated to cross the border of the Schengen zone and prolongue the legal limit to stay, especially if they took care of a more or less decent cover-up.

A Schengen visa costed 35 euro, taking two weeks to be issued. Getting an insurance for an additional 30 euro was often a pre-requirement in consulates. Also, if an applicant had to travel to another city with a consulate, he had to take two days off and spend some extra travel costs. Travelling for regular tourists was thus a complicated thing, but it was hardly a problem for Ukrainian illegal migrants, since they were determined to work abroad and viewed these costs as an investment.

Economic perspectives for Ukraine according to the World Bank

Economic perspectives for Ukraine according to the World Bank

People often used existing channels of illegal employment via personal contacts with previous migrants – mostly in Poland or southern European countries – to make the trip look like a tourist voyage or a visit to the relatives. This allowed them to obtain a visa, and then just remain in the country to work. Generally, if a Ukrainian sought illegal employment in the EU, it was never too complicated to find it.

Moldova could serve as an example. This neighbour of Ukraine has a poor population and now enjoys more than three years of visa-free movement, but no significant increase in Moldovan illegal workers in the EU was noticed. In a recent interview the former Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration of Moldova stated: the majority of Moldovans who wanted to find a job in the EU did so before the visa-free regime was introduced.

It is hard to say how many Ukrainians already work illegally in Europe. According to Eurostat, 29.670 Ukrainian nationals were ‘found to be illegally present’ in the EU in 2016 – fewer than 4% of all illegal migrants registered in Europe. Almost all of them were spotted with overdue visas at the border with Ukraine, as they returned home voluntarily.

Opportunities in Poland and Czech Republic

However, many more are likely to go unnoticed – in particular, seasonal jobs in neighbouring EU states, such as harvesting in Poland, are known to be quite popular among the poorer Ukrainians.Since the visa-free entry will require biometric passports from the incoming visitors, it would be easier to detect overstayers – and deport them with an entry ban. This is something Ukrainian migrants fear, since work abroad is often the main source of income for their families at home.

Luckily, the post-socialist countries of Central-Eastern Europe currently do a lot to offer legal jobs and education opportunities to Ukrainians. The relatively cheap, educated and productive workforce which can easily integrate into local life is viewed by Poland and the Czech Republic as a valuable asset.

Such opportunities are becoming increasingly popular, since there are already large communities of Ukrainians present and thus integration is easier; moreover, for the low-qualified workers who often do not speak any foreign languages, it is easier to learn the basics of a related Slavic language.

Countries like Italy, Portugal and Greece were attractive for Ukrainians. Migration channels from Ukraine existed – for instance, in employing Ukrainian construction workers. But as unemployment looms in the South, the popularity of these destinations will likely fall.

Western Europe: more risky

Western Europe is generally a more risky destination for job-seeking Ukrainians. Not ony the language and culture constitute a barrier, but also travelling there is more expensive, as are the costs of living. In addition, compared to Central-Eastern Europe, there are less low-qualified employment opportunities, especially in the last years. Moreover, in Western European countries, low-qualified Ukrainians would have to face tough competition for jobs with other recent immigrants.

Italy is the only popular country for Ukrainians in Western Europe

Instead, Western Europe, and Germany in particular, are actively attracting Ukrainian students – many of whom do not return home after their study – as well as natural scientists and technicians. According to a Ukrainian poll, 13% of those Ukrainians who would like to move permanently abroad (or 4% from the general population) want to do so for reasons of self-fulfillment – and they are likely to seek a place in the developed countries.

According to a 2014-2015 IOM study based on a household poll, 688.000 Ukrainians were working abroad, both through legal and illegal employment. Out of these workers, 33% worked in Russia and Belarus – and while some are likely to leave Russia because of the conflict between Moscow and Kyiv, many will continue to work there. Another third (35%) was working in Poland and the Czech Republic.

The only specifically popular Western European state with Ukrainian migrants is Italy: almost 12% of the foreign Ukrainian workforce works there and the majority of them stay for a longer period (many of them working as domestic helpers or in tourism). By 2015, according to this poll, no other European state attracted more than 20.000 Ukrainian workers – in most cases, their numbers are low as compared to other groups of nationals working in the EU.

Young Ukrainians

It is true that many, especially young, Ukrainians think about leaving the country, because the opportunities at home are limited. In a September 2016 poll, 41% of the Ukrainians answered positively to the question: ‘Would you like to work/obtain employment abroad?’ Among those aged between 18 and 35, more respondents (46%) preferred to leave than to stay. However, there is no reason to suspect that many of them would agree to move elsewhere for illegal work, that is mostly low-paid and comes with severe limitations. The IOM study indicates that only 21 % of Ukrainians who were actively planning to work abroad in the next year (estimated at 310.000 in 2010/15), would agree to do so illegally.

Young Ukrainians in Kyiv demand visa-free travelling to EU

Young Ukrainians in Kyiv demand visa-free travelling to EU

The highest percentage (37 %) of those who would accept employment abroad describe themselves as ‘well-off’ and with higher education, as compared to 22% among the poorest. Admittedly, they are well-off by Ukrainian standards; with 6.659 hryvnia (appr. 228 euro) average gross wage in Ukraine is low, compared to, for instance, Poland with 4.354 zloty (appr. 1.040 euro). But as the shadow economy in 2016 is 35 % of Ukrainian GDP, many Ukrainians – especially in cities – actually receive significantly more than they declare; also the costs of living in Ukraine are much lower than even in the neighbouring European countries.

In the end migration of a young, educated, well-off labor force could cause a problem of brain drain for Ukraine, but it would not substantially affect the EU. While some might exploit the visa-free regime for an opportunity to stay in Europe as illegal workers, it is unlikely that there will be a significant rise in Ukrainian migration due to travel liberalization.

Refugee route

Neither is it to be expected that Ukrainians will use the refugee status. While Polish PM Beata Szydlo famously stated that her country since the war in the Donbass ‘accepted a million of Ukrainian refugees’, in fact, only three refugees from Ukraine received asylum in Poland, and another 200 were granted protection. Her ‘million Ukrainians’ likely refers to the annual number of Polish visas issued to Ukrainian citizens.

As a result of the armed conflict in Ukraine, 1.7 million internally displaced persons relocated from the eastern regions to other parts of the country. They are facing problems receiving biometric passports, as they are being required to bring as many additional documents as possible, since Ukraine does not have access to their citizen records from their home cities. However, the majority of them did not opt for refugee status in Western countries. Whether they will look for employment opportunities abroad is an open question.

Young Ukrainians will visit Europe, spend their money and learn best practices

At the positive side, visa liberalization will cause many more Ukrainians – especially the young – to visit Europe, enjoy it, and spend their money there. It will stimulate transfer of best practices to Ukraine; grassroots-level urban activism in Kyiv and Lviv, for instance, is often initiated by Ukrainians who visited European cities and learned from their examples.

How important is the visa-free regime with the EU to Ukrainian citizens? As expected, the main beneficiaries of this change are young: 60% of the Ukrainians younger than 29 view visa-free movement as important for them.

The richer the person is, the more likely he is to view visa-free movement as personally important. Those who are neither poor nor ‘well-off’ might be looking forward to the new visa-regime with special eagerness. Earlier, they needed to certify their income when applying for the visa – a measure that discouraged students and numerous people whose official wages were much lower than the actual ones. With visa-free travel, nobody will check the entrant’s income – there is just a selective check on the money people have upon entering the country. Poeple with low incomes will just need to save a bit in order to visit Europe – and they will.

The polls indicate a large discrepancy in regional attitudes: in Western Ukraine, a pro-European stronghold, some 70% find the perspective of visa-free travelling to Europe important for their personal life. In the southern and eastern regions, where pro-Russian sentiments are traditionally strong, only 20 to 25% think likewise. People from the South-East thus might not only be less interested in European integration of Ukraine; they also care less about experiencing Europe in person.

It is safe to say that more Ukrainians will come to Europe in search of work in the coming years.The overwhelming majority of them will, however, use legal ways of employment – and will meet a demand in cheap and qualified workforce from the member states of the Central-Eastern Europe. And the main trigger for their decision to move would be the slow economic recovery in Ukraine.

At present, there is no indication that visa liberalization would lead to a peak in illegal migration from Ukraine to the European Union. As in the case of Moldova, the majority of those who wanted to work illegally in Europe already went West; visa regulations were never a significant barrier for them, as channels of avoiding these regulations have existed for a long time. Instead, the need to get a visa prevented many law-abiding Ukrainian tourists, and especially students, from travelling to Europe. Visa liberalization with Ukraine, therefore, is unlikely to hurt the EU to a notable extent, and will foster mutual contacts and understanding.