The NATO-summit with president Donald Trump, followed by his meeting with president Putin could mark a watershed in the relations between Europe and the United States. Trump doesn’t seem to acknowledge that American security guarantees are major instruments of U.S. self-interest and influence. And he thinks that charming Putin will be sufficient to repair the relations. Trump profoundly misunderstands the post World War II international order, writes security expert Hannes Adomeit.

On the eve of the meeting of NATO heads of state and government on 11 and 12 July in Brussels, the alliance is not only rife with internal conflicts, a fact of life that is nothing new in the history of the organization, but is also in danger of losing its very essence. It stands at risk of erosion of its core tenet cemented by Article 5 of the alliance’s charter, that ‘an attack against one ally is considered as an attack against all’. No other head of state or government since NATO was founded in 1949 has questioned that principle − until U.S. president Donald Trump. On 16 July, Trump will meet with Russian president Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, raising additional concerns over possible US concessions to Moscow and the precarious state of European security.

NATO secretary-general Stoltenberg during a recent visit in Washington on May 17

NATO secretary-general Stoltenberg during a recent visit in Washington on May 17

Like other positions damaging transatlantic cooperation and cohesion, Trump’s subversion of the NATO guarantee was clearly evident during the 2016 presidential campaign. It was to some extent reflected in the strange remark that he didn’t ‘mind NATO per se’ (!) and that the alliance was ‘obsolete’ in the sense that ‘we’re dealing with NATO from the days of the Soviet Union, which no longer exists. We need to either transition into terror or we need something else’. The alliance needed to be ‘reconstituted and had to be ‘modernized’.

As the context of the statement made clear, modernization requirements were not related to new threats from Putin’s Russia and its military intervention in Georgia, Crimea, eastern Ukraine and Syria, but to radical Islam. Furthermore, when he was asked about Russia’s threatening activities in the Baltic area and what would happen if Russia attacked the Baltic States, he said that he would decide whether to come to their aid only after reviewing if those nations have ‘fulfilled their obligations to us’. ‘If they fulfill their obligations to us’, he added, ‘the answer is yes.’

Trump has left no ambiguity as to what he considers to be the NATO partners’ main obligation. It is to live up to the commitment assumed by them at their summit meeting in Wales in September 2014 to increase their defence spending to 2 percent of their gross domestic products by 2024. To date, apart from the United States with 3.57 percent of defence expenditures as a share of GDP, only five of the 28 NATO members meet the 2 percent criterion − Britain, Poland, Estonia, Romania and Greece. Some other countries − France, Bulgaria, Hungary, Montenegro, Slovakia and Turkey − have plans to push their spending to the target. Thus, less than half of the members are committed to fulfill the Wales commitment, and that includes the biggest economic power of the alliance after the United States – Germany.

In the run-up to the Brussels summit, Trump ratcheted up the pressure on the delinquents. In a series of letters sent in June to NATO allies, including among others, Germany, Spain, The Netherlands, Norway and Canada, he demanded that they boost defence spending.

Trumps main target is Germany

The main target of Trump’s campaign, however, is Germany. In his letter to chancellor Merkel he charged that ‘continued German underspending on defense undermines the security of the alliance and provides validation for other allies that also do not plan to meet their military spending commitments, because others see you as a role model’. Even more pointedly, on 5 July he told supporters at a rally of supporters in Montana that, whereas the United States ‘pays 4 percent [sic] of its GDP’ on defence, ‘Germany, which is the biggest country of the EU […] pays one percent, one percent’. [The exact figure is 1.24 percent.] ‘I said, “You know, Angela, I can't guarantee it, but we're protecting you and it means a lot more to you than protecting us because I don't know how much protection we get by protecting you”.’

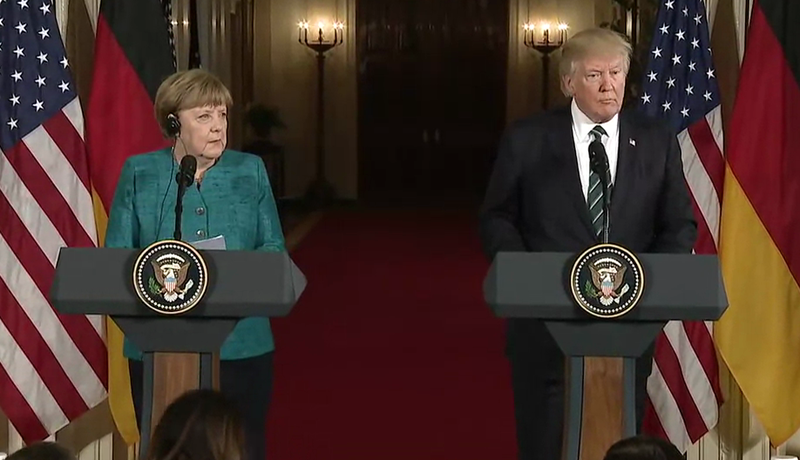

Merkel and Trump during Merkel's first visit to Washington in March 2017

Merkel and Trump during Merkel's first visit to Washington in March 2017

The rift that runs through German-American and thus transatlantic relations is significantly exacerbated by mutual personal dislikes and differences. It is almost as if Trump is joining Putin in a determined attempt to vilify, slander and impugn chancellor Merkel personally and destabilize Germany. He seems to sense that Merkel is unimpressed by his macho antics and feels treated like an ill-behaved school boy – ‘with condescension’, as White House staff has revealed.

Merkel stands for just about everything in international relations that Trump opposes

She stands for just about everything in international affairs that Trump opposes: she has insisted right from the start of his presidency that the basis for German-American friendship should be ‘shared values’. She supports the promotion of a rule-based, liberal democratic international order; advocates close cooperation in international institutions, including the UN, WTO and EU; is committed to safeguarding the rights of asylum seekers and refugees, pointing out in reference to Trump’s travel ban that the ‘battle against terrorism does not in any way justify putting groups of certain people under general suspicion, in this case, people of Muslim belief’; considers the Iranian nuclear agreement to be effective, malign behavior by Tehran on other issues to be treated separately; continues to adhere to the Paris international climate accord; and is opposed to US extraterritorial or secondary sanctions against entities violating US laws pertaining to Iran and pipelines such as Nord Stream 2.

Interests versus values

Trump, in contrast, has made it clear that interests, American interests, are his primary concern, and values secondary. He loathes being bound by international frameworks and thus wants to conclude bilateral agreements; has decried the Iranian nuclear agreement ‘disastrous’, ‘catastrophic’ and ‘the worst deal ever’ and thus abrogated it; called global warming a ‘hoax’ and a concept that was created ‘by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive’, and left the Paris climate accord; grounded plans for the realization of a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and a Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership (TPP) and put the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in jeopardy; directed trade officials to draft a bill that would allow the US to abandon its WTO commitments; withdrew from the UN Human Rights Council; claimed that Merkel’s decision to keep open the country’s borders to Syrian refugees was ‘insane’, insinuating that Europe had made the big mistake of letting in millions of people who had ‘violently’ changed the culture, and that ‘crime in Germany is way up’; asserted that the EU was ‘possibly as bad as China’ and ‘set up to take advantage of the United States, to attack our piggy bank’, welcomed Brexit and encouraged president Macron to pull France out of the EU, dangling an enhanced trade deal as a reward; and, in reference to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, attacked Germany, saying that it wanted protection against Russia yet ‘they go out and make a gas deal, [import] oil and gas from Russia and [thus] pay billions and billions of dollars to Russia’.

Trump won't be satisfied

The German government has reacted to Trump’s demands. It has announced that it will boost military spending in 2019 by 4 billion euros to 42.9 billion euros, its fourth successive year increase. That would bring up the share of defense expenditures to 1.31 percent of economic output. Furthermore, Berlin stated that it would raise the percentage to 1.5 percent by 2024 and that it remained committed to achieving the NATO target of spending 2 percent at a later date. What bodes ill for both the Brussels summit and future German-American relations, however, is the fact that even if Germany were to reach that target, it would not satisfy Trump.

This is the conclusion that one has to draw from the letter sent by U.S. secretary of defence Jim Mattis to his British colleague, defence secretary Gavin Williamson, on June 12. Mattis acknowledged that Britain is one of the few NATO allies that meets the alliance’s 2 percent target but said that this was not good enough. Britain’s global role, he insisted, ‘will require a level of defense spending beyond what we would expect from allies with only regional interests’. He also expressed concern that ‘your ability to continue to provide this critical military foundation [...] is at risk of erosion’ and expected from Britain a ‘clear and fully funded, forward defense blueprint’.

American forces

Germany is a major target of Trump’s ire also because of the large-scale presence of U.S. forces there. In the context of the review he has ordered of the utility and costs of US forces stationed abroad, he was reportedly taken aback when he learned that 35,000 active-duty troops are stationed in Germany, which is the biggest US military contingent in Europe. (In Japan the US troop presence amounts to about 39,300 and in South Korea 23,500). It is little consolation to European NATO members ahead of the Brussels summit that the Pentagon has given assurances that ‘it is nothing new’ that it ‘regularly reviews force posture and performs cost-benefit analyses’, including of the forces stationed in Germany, and that ‘we remain deeply rooted in the common values and strong relationships between our countries. We remain fully committed to our NATO ally and the NATO alliance.’

American secretary of defence Mattis meets with German, Lithuanian, Dutch, Belgian and American troops training in Lithuania, May 2017. Photo U.S. Air Force

American secretary of defence Mattis meets with German, Lithuanian, Dutch, Belgian and American troops training in Lithuania, May 2017. Photo U.S. Air Force

Trump has repeatedly demonstrated that he is quite prepared to ignore pleas and advice by his cabinet ministers and security advisers, and fire them if they insist, and to disregard vital interests by allies. This also concerns South Korea. As a candidate in the Republican primaries in March 2016, underlining the utter consistency of his stance on achieving financial savings by withdrawing U.S. forces world-wide and shifting defence burdens to allies, he suggested that the US should consider allowing Japan and South Korea to develop nuclear weapons so as to deter North Korea: After all, ‘Pakistan has it [the nuclear weapon], China has it. You have so many other countries are now having it.’

Furthermore, in the hastily arranged meeting with Kim Jong-un to achieve the ‘complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization’ of North Korea, without consulting or informing Seoul he rode roughshod over South Korean security interests and announced the suspension of joint military exercises. To add insult to injury, he used Pyongyang’s terminology when he called the maneuvers ‘provocative’. Is there a lesson to be learned by Germany and other European NATO members? Consistently, Russia has used the same term for NATO maneuvers in Poland and the Baltic States.

Security guarantees benefit U.S.

Trump, thus, profoundly misunderstands the post-World War II international order. U.S. security guarantees benefit the U.S. far more than any ‘tribute’ from the European NATO member countries, Japan or South Korea would. U.S. forces and security guarantees are not bonuses and benefits liberally distributed by a benevolent Uncle Sam. They are major instruments of in U.S. self-interest and solid ‘investments’ to safeguard American political and economic influence in Europe and Asia. They also help prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, and thus limit the risk of nuclear war.

Trump’s misunderstanding is compounded by a paradox that concerns the purpose of potential increases in defence expenditures. When NATO agreed on the 2 percent target, this was in response to Russia’s occupation of the Crimea and its military intervention in eastern Ukraine, that is, in response to new military threats emanating from Moscow. Yet Trump has never uttered a critical word about Putin and has consistently downplayed potential Russian challenges and threats. Concerning the Crimea, Trump has never criticized Russia or Putin for its seizure. On the contrary, he has appeared to legitimize it by saying that ‘the people of Crimea, from what I’ve heard, would rather be with Russia than where they were’.

During the G7 summit in Quebec in June, he doubled down on his call for Russia to be readmitted into the group, mentioning that Russia has invested heavily in Crimea since the annexation. ‘They’ve spent a lot of money on rebuilding it’, he said. (Russia was expelled from the body over Crimea.) And in the run-up to the Helsinki summit, he even left the door open to recognizing the annexation, telling reporters that such a move would be up for discussion with Putin. ‘We’re going to have to see‘, he said.

It is absurd for Trump to claim the 'no one is tougher on Russia'

Thus, it is absurd for Trump to claim that ‘no one is tougher on Russia’. He has not only denied any collusion of his campaign with Russia but also never publicly accepted the conclusion of the US secret services that Putin personally ordered or authorized the massive interference in the 2016 electoral campaign. In view of his failure on the two occasions when he met Putin in person – at the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Hamburg in July 2017 and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Vietnam in November of the same year – to take Putin to task, it must appear meaningless that the White House confirms that Trump will talk about this issue with him also in Helsinki.

Shocking treatment of close allies

In view of Trump’s shocking treatment of close allies at the Singapore summit with Kim Jong-un and the G7 meeting in Quebec, it would be naïve to expect from the NATO summit in Brussels any significant improvement of transatlantic relations or from the Trump-Putin meeting in Helsinki an amelioration of Russia’s relations with the West. It is more than likely that, as on the Paris climate accord, the Iran nuclear agreement and on trade policy, he will stubbornly cling to positions he has strongly held even before he was a presidential candidate. Concerning NATO, this includes the demand its members have to step up to the plate and do much more for their own defence and meet their commitment of spending at the very minimum of 2 percent of GDP on defence. Since not only Germany but other NATO countries as well are not going to meet the minimum target, the best that can be expected from the Brussels is the avoidance of an éclat along the scales of Quebec.

Concerning Russia, as on North Korea, he appears to believe that personal diplomacy can radically turn the relationship around and that he can charm Putin to … well, to do what? Since he has not made Putin’s assertive and aggressive behavior a bone of contention, neither in public nor, as far as one knows, in conversation with the Kremlin chief, he does not appear to require any major policy shift from Moscow. There is, however, one major exception. When Trump’s national security advisor, John Bolton, visited Moscow in June in preparation for the Helsinki summit, he said that the president would seek Russia’s help to oust Iran from the Syrian battlefield. Later, he confirmed that idea and said that the summit offered the possibility of a ‘larger negotiation on helping to get Iranian forces out of Syria’ and that such a deal would amount to ‘a significant step forward’ in promoting U.S. interests in the region, which include curbing Iran’s influence.

No ground for optimism

Such considerations reveal an unrealistic view of Russian interests and overestimation of the degree of leverage Moscow may have over Tehran. Nevertheless, analysts like Carnegie’s Dmitri Trenin, Eugene Rumer and Andrew Weiss have concluded that ‘the experience of the Singapore summit suggests that such encounters can create a positive atmosphere for the real hard work of repairing relations to begin. The Trump-Putin summit potentially can accomplish the same, very important results. It can empower the reasonable voices to begin the conversation in earnest about the state of the relationship, about ways to repair it, and, at the very least, a mutually acceptable way for managing it’ . It is highly doubtful that such optimism is warranted. One should perhaps be content if Brussels does not end in a similar éclat like Quebec, and Helsinki not like Singapore in a series of U.S. concessions without guarantees of their implementation.