The image of Putin’s Russia in Germany has suffered tremendously in the past few weeks. In the wake of a series of ever more implausible denials, the Kremlin’s credibility has seriously been eroded. Government and leading figures in the political parties have called for sanctions, both against the Lukashenko regime and Putin’s Russia, including stopping the North Stream 2 gas pipeline project. It remains to be seen whether the current shocks of the Kremlin’s behaviour will lead to major policy changes or, as in the past, end in business as usual.

Will Germany decide for major changes in its Russia-policy? Picture Bundesregierung.de

Will Germany decide for major changes in its Russia-policy? Picture Bundesregierung.de

Changes in German perceptions and policies towards Russia obviously are crucially important because for decades the German government and public opinion have been favourably disposed towards Russia. Up to and until Moscow’s annexation of the Crimea and its intervention in eastern Ukraine, Berlin stubbornly clung to the idea of a ‘strategic partnership’ with Moscow and to provide for its foundation through a ‘modernisation partnership’. It also was the driving force behind the European Union’s Russia policy. Its role at present has assumed even greater significance as it holds the EU Council chair.

Today, even some the most vociferous and ardent representatives of the camp of Putin- and Russland-Versteher, that is, those who claim to ‘really’ understand the Kremlin, invariably find excuses for its behaviour and call for ‘dialogue’, have come to have doubts.

In Lukashenko's refusal to open a dialogue with the opposition Russia looms large. Photo: screenshot Pul 1

In Lukashenko's refusal to open a dialogue with the opposition Russia looms large. Photo: screenshot Pul 1

Objectively and in the view of the German government and the public, the ‘Russian factor’ is looming large in Belarusian strongman Alexander Lukashenko’s stubborn refusal to open a dialogue with the opposition and to share power, let alone to leave power. Just like in the case of Ukraine’s Euromaidan, Putin and Lukashenko have claimed that the large-scale demonstrations against the regime are organised and financed from abroad and, as Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov asserted, an issue of ‘geopolitics’ and the ‘struggle for the post-Soviet space’.

Putin has used that frame of reference to promise ‘comprehensive aid’ to Belarus upon request in the event of ‘external military interference’. In turn, Lukashenko told his Russian counterpart that the protests in his country were not only a threat to Belarus but also to Russia and that, therefore, ‘the defence of Belarus today is nothing less than the defence of our entire territory’, the Union state of the Russian Federation and Belarus.

Belarus and die Linke

Assessments by the German government and political parties of the developments in Belarus and the coordination between Minsk and Moscow, with one exception, present no surprises. The ruling parties of Conservatives (CDU/CSU) and Social Democrats (SPD) as well as the Liberals (FDP) in opposition all agree that the official result of 80 percent for Lukashenko in the 9 August presidential election do not reflect reality, and they condemn the police brutality in the attempted suppression of the large-scale demonstrations. The right wing populists (AfD), who in the previous year had sent observers to the parliamentary elections in Belarus and had found little to criticize, simply ignore the Lukashenko problem.

The exception to previous attitudes has proved to be the Left (Die Linke). Jörg Schindler, the party’s managing director, expressed his concern about the ‘shocking reports of election fraud, violence and torture in Belarus’. These actions, he said, required a ‘decisive and coordinated response from the European states. The German government must exhaust all diplomatic means to that effect [and it must] recognise political persecution of opponents of the regime in Belarus as grounds for granting asylum in Germany and Europe.’ Why this surprising condemnation of political persecution and human rights violations in Belarus? It has in all likelihood much to do with the ‘deep concern’ expressed by Jörg Schindler, the party’s executive director, about the fate of Pavel Katarzheuski, board member of Die Linke’s partner party Gerechte Welt (Just World) in Belarus, who was arrested during the protests.

What to do?

But what to do? How to react to the developments in Belarus? The German government’s position is amply reflected in the conclusions of the EU’s emergency summit of 19 August. EU leaders called for dialogue and for a peaceful transition of power; pledged money to Belarus civil society, independent media, victims of the crackdown and to fight Covid-19; and warned of Russian meddling in the country's affairs. The EU also said that it would soon impose sanctions on a ‘substantial number’ of individuals responsible for violence, repression, and election fraud. The EU, however, did not call for fresh elections. It also did not offer to mediate itself, but supported the idea of dialogue proposed by the OSCE. ‘Belarus must find its own path […] and there must be no intervention from outside’, Merkel said after the videoconference of leaders. Solutions should be found ‘via dialogue in the country’, and the dialogue should include Lukashenko.

Police clamps downs during protest by Belarussian students. Photo twitter

Police clamps downs during protest by Belarussian students. Photo twitter

Europe, however, is severely constrained in its reactions. Just like any military move, tough economic sanctions are out of question. They would hurt the population and force Lukashenko to beg for economic assistance to which Putin might agree – for a price, however, which in all likelihood would be more ‘integration’, that is, the de facto subordination of Belarus to Russia. Substantial rather than symbolic financial support for opposition political movements and parties and civil society are also problematic. They not only raise the practical issue as to how they could be administered but, even more importantly, they they would almost certainly be used by Minsk and Moscow as proof that the EU is attempting to launch another ‘colour revolution’. Finally, mediation and ‘dialogue’ have been ruled out by Lukashenka, most likely in agreement with Putin. Thus, speaking in Berlin after the EU summit, chancellor Merkel said that she did not see an immediate possibility for mediation to resolve the situation in Belarus. She had tried to phone Lukashenko but ‘he refused to talk to me, which I regret’.

The issue of sanctions, not against Belarus but against Russia, has also arisen in the context of the poisoning of Navalny.

The impact of the poisoning of Navalny

This event first and foremost concerns Germany – not only because of its EU Council chairmanship but because of the connection of the poisoning with the Lukashenko problem; the fact that Navalny upon request of his wife and supporters in Russia was transferred for diagnosis and treatment to the Charité university research and medical care institution in Berlin; the reminder that that two years earlier, Pyotr Verzilov, another critic of the Putin system, was admitted to the Charité for treatment of a poisoning; the murder of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, a 40-year-old former Chechen rebel commander, in broad daylight in Berlin, with the German federal prosecutors filing charges against a Russian citizen who, they said, had acted on orders of ‘state agencies of the central government of Russia’ to ‘liquidate’ the victim; the parallels with previous murder or murder attempts such as against Litvinenko, Skripal and Kara-Murza; and the current revelations about the (failed) murder attempts in Bulgaria against an arms manufacturer, his son, and the production chief of his group of plants.

Navalny was transported to Berlin upon request of his wife and supporters. Photo from twitter

Navalny was transported to Berlin upon request of his wife and supporters. Photo from twitter

The sensitivity and political significance of the poisoning was underlined by the fact that chancellor Merkel was visibly outraged and deeply offended by it. On 2 September she took it upon herself to announce the zweifelsfrei, that there could be ‘no doubt’ about it. In emotional terms she It was evident to her that the victim ‘was to be silenced’ as a critic of the regime. The poisoning, she concluded, ‘raises very serious questions that only the Russian government can and must answer’.

Lukashenko aligned himself with the Russian position that Moscow had nothing to do with the poisoning − if, indeed, there had been any. On 3 September he told Russia’s visiting prime minister Mikhail Mishustin that the German chancellor had falsely stated (‘falsified’ a statement) that Navalny was poisoned. ‘We intercepted a conversation between Warsaw and Berlin before Merkel’s statement […] which clearly proves that it is a falsification.’ The purpose of the falsehoods spread by Berlin, he claimed, was to ‘discourage’ Putin to involve himself in ‘Belarusian affairs’. Testifying to the close alignment of the official Russian and Belarusian position, Sergey Naryshkin, who heads Russia’s SVR foreign intelligence service, said that it was quite ‘possible’ that Navalny’s poisoning was a ‘provocation’ by Western intelligence agencies and that, ‘If the president of Belarus said it, then he had reason’ to do so’.

Merkel's personal indignation

Chancellor Merkel’s personal indignation about Putin’s Russia and its recurrent denials of responsibility had become apparent just as few months earlier, in connection with the findings presented by the federal prosecutors concerning the largest cyber attack to date against the Bundestag in May 2015. Computers in numerous parliamentary offices had been infected with spy software, including the computers in Merkel's Bundestag office. The hackers had also captured emails from the chancellor's office on a large scale, containing correspondence from 2012 to 2015. The prosecutors blamed the Russian military intelligence service GRU for the large-scale cyber attack. Speaking in the Bundestag in May of this year, Merkel accepted he findings as ‘hard evidence’ for Russian involvement and spoke of an ‘outrageous’ process and that she was taking ‘these things very seriously’.

Speaking in the Bundestag on 13 May 2020, she deplored that ‘Russia is pursuing a strategy off hybrid warfare. We cannot push this aside. That’s warfare in the form of a [campaign of] disorientation and disinformation in cyber space. It is a [deliberate] strategy, not some random occurrence.’

Merkel’s portrayal is fully in accord with that of foreign minister Heiko Maas (SPD). Shortly after his appointment to this position, in an interview with Der Spiegel, he stated that Russia’s international behaviour had become ‘increasingly hostile’. In reference to the Skripal case, he deplored that for the first time since the end of the Second World War, a European country had ‘used chemical weapons.’ Cyber attacks appeared to have become an ‘integral part’ of Russian foreign policy. Concerning the war in Syria, he decried that Russia had ‘repeatedly blocked’ the UN Security Council and prevented a political solution. It had carried out ‘aggression’ in Ukraine. Sanctions, he warned, could only be lifted after Russia had fulfilled all of its obligations under the Minsk agreements.

This raises the general issue as to how to deal with and essentially hostile Russia, whether sanctions should be used and, if so, what kind.

To sanction, or not to sanction, that is the question

The central focus of the sanctions issue has been the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project, that is, whether the project should be stopped. The issue has revealed deep splits between and within the German political parties. The major part of the CDU seems to be in favour of this step. For Christian Lindner, FDP chairman, ‘a regime that organizes murders with the use of poison cannot be a partner for large cooperation projects, including pipeline projects’. The leader of the Greens in parliament, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, concurred, saying that ‘The apparent attempted murder by the Kremlin's mafia-like structures can no longer just worry us. It has to have real consequences.’

Former German Chanceller Gerhard Schroeder chairs the board of Nordstream 2. Photo Gazprom

Former German Chanceller Gerhard Schroeder chairs the board of Nordstream 2. Photo Gazprom

The issue, however, has been controversial within the political parties. Lindner has modified his stance by replacing the word ‘termination’ by ‘moratorium’. However, his deputy, Wolfgang Kubicki, has rejected the whole idea.

The split extends to government coalition partner SPD. Ex-chancellor Gerhard Schröder, chairman of the board of directors of Nord Stream 2 AG, a subsidiary of the Russian state-run gas company Gazprom, as well as chairman of the board of Rosneft, the giant Russian state-controlled oil producer, thus far has been quiet but there can be no doubt that he is vehemently opposed to any stop or moratorium. SPD party chairman Norbert Walter-Borjans opposed to linking Nord Stream 2 with the attempted murder of Navalny. Foreign minister Maas, however, has drawn this link and on 6 September increased pressure on Russia. He warned that lack of support by Moscow in the investigation of the attempted murder could ‘force’ Germany to rethink the fate of the pipeline project.

As several European countries have been opposed from the very beginning to Nord Stream 1 and 2, Merkel’s insistence that the EU should be in the lead if the project was to be stopped could be an indication that she would like to shift at least part of the responsibility for the termination to Brussels.

In contrast to the government and political parties with their representatives, one searches in vain for any sign of indignation, outrage or embarrassment, let alone of any reconsideration of attitudes and policies towards Putin’s Russia in the camp of the Russland-Versteher. It adheres, in essence, to what Sevim Dagdelen, chairwoman of Die Linke parliamentary group in the foreign affairs committee had said prior to the talks to be held on 11 August by foreign minister Maas with Lavrov in Moscow. The talks, she thought, should be a good opportunity to announce an end to the EU’s ‘punitive measures’ against Russia and to refrain from conducting ‘economic warfare’ against the country. She came out in support of sanctions but not against Russia. ‘Die Linke’, she said, ‘calls on the federal government to condemn the most recent attempts at blackmail by the United States against German companies and citizens to prevent Nord Stream 2 and to consult with Russia on suitable countermeasures.’

Opposition to sanctions from the left and the right

The right-wing populist AfD has joined Die Linke and other apologists of Putin’s policies. Like in the Litvinenko, Skripal, Kangoshvili and other such cases, they have rejected the German government’s position (as mentioned) that there was no doubt that Navalny was poisoned in Russia with the nerve gas Novichok. They have warned against ‘rash accusations’ and argued that it was inadmissible to issue a ‘guilty’ verdict before all the facts had been established. The apologists are evidently in denial of the fact that even when, after thorough investigations and the presentation of incontrovertible evidence, the responsibility of the Russian state institutions has been established without reasonable doubt and the perpetrators have been named, the Kremlin continues to reject any responsibility.

Their opposition to sanctions against Russia, be it on Nord Stream 2 or any other issue, is a matter of principle. For others it is a matter of expediency. They argue that sanctions against Russia, as those imposed on Russia after its annexation of the Crimea and intervention in eastern Ukraine, are generally ‘ineffective’ and even ‘counterproductive’; that they hurt German business and industry; and that, concerning Nord Stream 2, they would 'endanger German energy security'. However, while the German economics ministry puts Russia’s share in German natural gas imports at ‘about 40 percent’, natural gas accounts for only about a quarter of total energy consumption, so that the possibility of Russia exerting pressure, apart from damaging its position as reliable supplier and hurting its economy, is minimal.

Furthermore, projections for future German and EU gas demand vary widely, with some calling into question the need for additional import capacities. In a 2018 paper, for instance, the German Institute for Economic Research ( DIW) wrote that the energy consumption forecasts on which Nord Stream 2 is based, ‘significantly overestimate natural gas demand in Germany and Europe’ and that there will be no supply gap if the pipeline were not to be built.

In addition, as a research team of Der Spiegel has pointed out, the companies involved in the project several years ago prepared for possible political difficulties. In 2016, the Russian conglomerate Gazprom took over the entire project as sole shareholder. The five European stakeholders that had been involved up to that point - Uniper and Wintershall in Germany, Shell in the Netherlands, OMV in Austria and Engie in France – limited their involvement to covering 10 percent each of the planned construction costs of around 9.5 billion euros. That money has already been paid out in full. Should it come to termination of the project, they may have to write off their investments. A loss of almost a billion euros each would, of course, be painful, but is part of the risk of doing business for companies of that size.

Doubts about the effectiveness

Another facet of the sanctions issue is their likely effectiveness to change Russian behaviour. Some scepticism is well in place.

Putin and the narrow circle of his friends and associates do not make decisions in accordance with economic rationality but security in the sense of internal security and maintaining their grip on power. Furthermore, ever since Putin was placed in power by the Yeltsin ‘family’, he has − as a matter of top priority and with great determination − pursued the goal of immunising Russia as much as possible against economic and financial pressure from the West.

In his perception, the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Baltic States had happened because of severe pressure exerted by the United States as witnessed by the United States Senate passage of an amendment to the foreign aid bill that would have cut off all American credits to Russia unless Moscow's troops were out of Estonia by 31 August 1994. One of the many indications of this policy priority has been Russia’s accumulation of various stabilization and reserve funds amounting at present to 592 billion USD in hard currency.

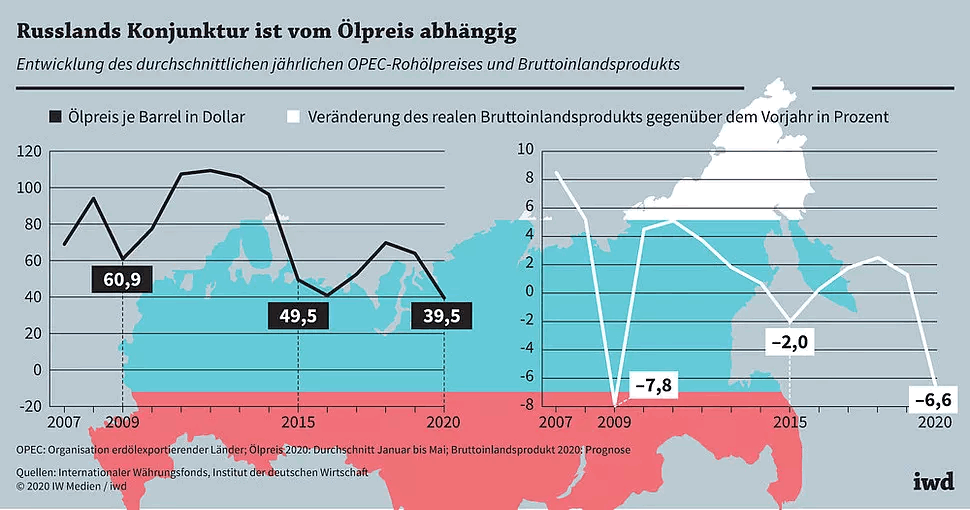

The Russian growth has been hampered by economic sanctions. Graphic IWD.de

The Russian growth has been hampered by economic sanctions. Graphic IWD.de

Nevertheless, according to estimates by German research institutes, if it had not been for sanctions, Russia’s current GDP would be six percent higher that it would have been if the country had continued on the pre-2014 growth trajectory. Just as important, one needs to take into account the so-called ‘opportunity costs’, that is, the likely losses incurred because of the cancelation of actual and the shelving of planned or possible European and American investments.

Finally, critics of the sanctions policy have to answer the question as to what ‘message’ the failure to apply them would, in the case of Crimea and eastern Ukraine, have sent to the Kremlin and what it would likely send in current conditions.

Change of mind or business as usual?

The cumulative impact of Russian support, up to the threat of military intervention, for Lukashenko’s internal repression and his refusal to embark on any compromises, and the Kremlin’s denials and absurd claims that Navalny may have been poisoned in Berlin rather than in Tomsk, has given new impetus to the controversies in Germany about the essence of the Putin regime and its domestic and foreign policies.

Perceptions among government officials, political parties and the public are increasingly coming to the conclusion that the Putin system is akin to a criminal syndicate and that it has turned from being an actual or potential partner to a foe.

There has also been an increasing realisation that what is at issue, as Merkel and Maas have stated, a deliberate Russian ‘strategy’ with the goal of disorienting and destabilising Western democracies and undercutting European integration and transatlantic cooperation by means of ‘hybrid warfare’. This has, therefore, sharpened again the perennial and vexing debate, virulent also during the Cold War, as to how to cope with or ‘manage’ the Russia problem.

Current trends of the debate are that dialogue, compromise and concessions will not induce Moscow to change its attitudes and policies.

An outstanding example of this view is Wolfgang Ischinger, one of the most experienced German diplomats and at present chairman of the Munich Security Conference. In the fifteen years of Merkel's chancellorship, he has argued, she had shown Eselsgeduld, almost boundless patience, but for Putin only the Recht des Stärkeren counted, the notion that might makes right. The only way to deal with Putin as with any other autocrat was to be equally tough and uncompromising. The Germans, he thought, were adept at using soft power in international relations but soft power without hard power was 'like a football team without a goalkeeper'. Germany and Europe had to be able to defend their interests more effectively and render themselves less susceptible to blackmail by leaders like Putin. That could not be achieved without military backing. This did not mean that Europe should use military power offensively, but it had to be able to provide effective deterrence.

Such calls were heard in previous years, including by then president Joachim Gauck and defence minister Ursula von der Leyen in 2014, but these were uttered as more or less philosophical considerations, not specifically proposed as a remedy to cope with the Russian challenge. It remains to be seen whether the current shocks of the Kremlin’s behaviour will lead to major policy changes or, as in the past, end in business as usual.